During the 1990s, the Falun Gong meditation and spiritual practice emerged as a popular health, fitness, and Qigong activity in China, partly thanks to official support. Flying below the radar of international media and even parts of the Communist Party itself, the group grew to encompass tens of millions of practitioners from diverse professions, social status, and locations across China. In the late 1990s, Falun Gong gradually transitioned from being officially endorsed to being harassed. In July 1999, it dramatically and abruptly became the target of a massive eradication effort.

In advance of July 20, the 20th anniversary of the launch of one of the largest campaigns of religious persecution in modern China, I reached out to various contacts I had met over the years and when researching a 2017 Freedom House report on religion in China to gather recollections of this fateful moment from Falun Gong believers, torture survivors, and other prominent Chinese activists.

Here eight individuals describe life before the ban, how the early days of the campaign unfolded, its impact on the lives of many Chinese, and the reverberations throughout China 20 years later. One of the striking commonalities in their testimonies is how many personally know friends, neighbors, or family members who practiced Falun Gong and have died due to police abuse, offering a glimpse of the scale of human loss unleashed by the CCP two decades ago.

Bu Dongwei, Falun Gong practitioner and labor camp survivor aided by Amnesty International, now living in California

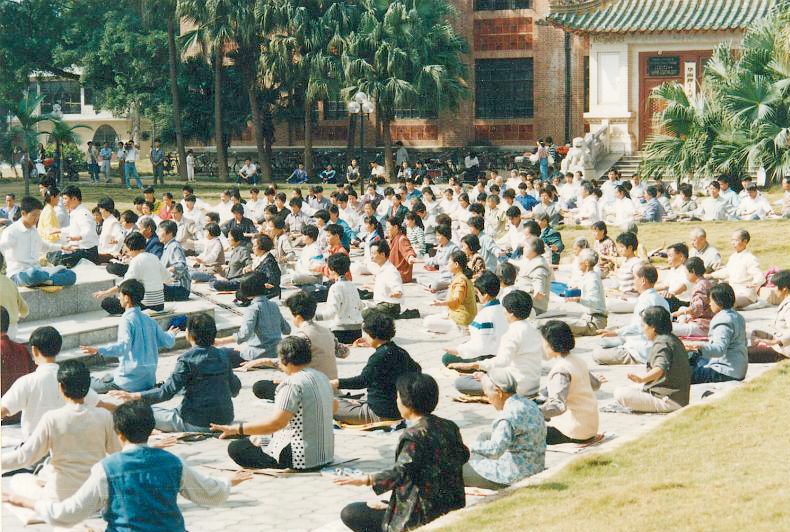

Before July 1999, I lived in Beijing and you could see people in the morning doing Falun Gong exercises in almost every park in the city. On the weekends, my wife and I would go to the nearby Capital Indoor Stadium to do the meditation exercises. Usually there were over 2,000 people there.

I was in Beijing on July 20, 1999. My first reaction on hearing the news was that I thought it was not right for the CCP to ban such a good practice. I was working at a large state-owned company at the time and after July 20, my life totally changed. The general manager and party secretary in our company tried to force me to give up Falun Gong. I refused and could feel pressure at the company. My wife and I decided to write letters to China’s top leaders, thinking they had misunderstood Falun Gong and asking them to re-investigate the practice. We were arrested in July 2000 and sent to labor camps.

In 2006, when I was working at the Beijing office of the U.S.-based Asia Foundation, I was arrested again just because police found several Falun Gong books in my home. I was put in a labor camp for over two years. Amnesty International listed me as a prisoner of conscience and its members wrote thousands of letters to me. I did not receive even one. Still, with the help of the U.S. government and international community, I came to United States with my daughter in November 2008 after being released from the labor camp.

Three of my personal friends were not so lucky. They died as a result of the persecution, including one who was tortured to death at Beijing’s Fangshan detention center in 2004 at the age of 47.

Yang Jianli, former Chinese prisoner of conscience and founder of Initiatives for China, now living in Washington, D.C.

I first heard about Falun Gong in the 1990s from a professor who studied post-Tiananmen Chinese society. We thought it was just one of many traditional Chinese Qigong groups that had flourished after the Tiananmen incident for two reasons: to fill the vacuum of beliefs left by loss of faith in Communist ideology and to engage in self-assisted health practices because there was no adequate insurance system.

On July 20, 1999, I was at UC Berkeley hosting an academic conference when I heard that Falun Gong had been banned. I was not entirely surprised because I had a clear sense that, sooner or later, groups like Falun Gong would run into the CCP’s repressive apparatus because the party is suspicious of any group organized outside itself, especially those with a different belief system. But I was surprised that Falun Gong had developed into such a large movement. I didn’t realize the scale until I saw how massive the CCP-enforced persecution was. I was among the first group of Chinese dissidents who stood up with Falun Gong practitioners to condemn the persecution.

When I was imprisoned in China for my activism from 2002 to 2007, there were several Falun Gong practitioners jailed with me. They received especially harsh treatment because it was very difficult, almost impossible, for the guards to subdue their independent thought. The authorities applied different tactics to different Falun Gong prisoners to try to get them to renounce their faith. For some, they sent well-trained police “psychologists” to talk to them. For others, they beat them. In both cases, I could hear shouting from their cells, either calls of “Falun Dafa is Good” or screaming because of torture.

If the CCP’s anti-Falun Gong campaign taught me anything, it was that the CCP will not allow any group to have freedom and that we must work together to stand up to the regime and support each other.

Meanwhile, the CCP’s anti-Falun Gong campaign has actually helped spread the practice both within and outside China. The group has emerged as one of the most strident critics of the CCP. Falun Gong practitioners have been particularly resilient in their resistance, posing a sustained challenge to the CCP. They have made remarkable contributions to technologies helping people back in China get around the Great Firewall. All of this has contributed to the Chinese public’s knowledge and understanding of the nature of the CCP. It has empowered people with information and tactics to engage in human rights defending work for themselves.

In a sense, in July 1999, the CCP created exactly what it had feared.

Yolanda Yao, Falun Gong practitioner and torture survivor living in California, whose parents are currently jailed in China

In the late 1990s I lived in Nanyang in Henan Province and practiced Falun Gong openly. Many people in the city practiced it in parks after work every day, including my teachers and neighbors. I was a junior high school student on July 20, 1999 when I heard that Falun Gong had been banned. I was shocked. My school held meetings to slander Falun Gong and forced all students to sign guarantees that they wouldn’t practice, otherwise you couldn’t pass the high school entrance exam.

Twelve years later, I was completing a Ph.D. in Beijing. My studies were abruptly interrupted on October 23, 2011, when I was arrested for practicing Falun Gong and sent to the Beijing Women’s Labor Camp for 20 months. There I faced around-the-clock brainwashing sessions and unrelenting mental and physical torture. I was forced to sit on a child-size chair for over 10 hours every day. This caused my legs and feet to swell, ending with my back and hip being bruised and ulcerated. The use of toilets was severely restricted causing incontinence and urinary tract infections. I was forced to do heavy labor in summer temperatures surpassing 100 degrees Fahrenheit and was once soaked in pesticide when a 70-pound barrel carried on my back leaked. Sleep deprivation was routine in the labor camp and most nights I was only allowed three hours of sleep before the grueling physical labor began.

I escaped to the United States, but my parents remain in China. They were arrested on December 5, 2015 when police raided their home while they and others were practicing Falun Gong. Each was sentenced to 4.5 years in prison for possessing and sharing materials about Falun Gong, as well for jumping the Great Firewall. They are both still in prison, and I cannot call or write to them. I worry if I will ever get to see them again. Thousands of Falun Gong practitioners have died due to the persecution — including one of our neighbors who was only 38 years old when he passed away.

Teng Biao, prominent Chinese human rights lawyer, now living in Princeton, New Jersey

I was doing a Ph.D. at Peking University in Beijing on July 20, 1999, when I heard the news that Falun Gong had been banned. My first reaction was that it seemed to be the beginning of a new political movement initiated by the CCP and it was apparently against the rule of law. I had previously expected there would be a ban and persecution, but it was still a surprise for me years later when I learned how extremely brutal the persecution was.

Right after the crackdown, all students were required to write down their opinions and hand them in. Unlike most of the others who echoed the official propaganda, I challenged the persecution and called for rule of law and religious freedom. In 2007, I participated in the first defense team in China to publicly defend Falun Gong and challenge the legal basis of the persecution.

I was then disbarred, deprived of my passport, banned from the media, forbidden from teaching, assaulted, kidnapped, forced to disappear three times, had my home raided by officers, and was severely tortured. Many of my lawyer friends represented the cases of Falun Gong practitioners who had been tortured to death or curiously died in custody. Two famous Chinese human rights lawyers that I know, Gao Zhisheng and Wang Quanzhang, bravely defended Falun Gong, and are still disappeared or in detention for their work.

The horrible campaign against Falun Gong has made many people live in fear. Most people are afraid of even mentioning Falun Gong. But many Falun Gong practitioners have insisted on resisting persecution, risking their freedom and even their lives. More and more intellectuals and lawyers have also started to speak up for Falun Gong practitioners, despite this being a forbidden zone.

Falun Gong practitioners meditating in public in Guangzhou in 1998, before the Communist Party banned the spiritual group in 1999. Credit: Minghui via Freedom House.

Crystal Chen, Falun Gong practitioner and torture survivor, now living in Texas

I learned Falun Gong in Guangzhou, Guangdong province in 1997 with my mother. She had suffered a terrible stroke, paralysis, and breast cancer but recovered after a few months of taking up the practice. Falun Gong was very popular in the city back then. Besides meditation sites in all the parks, there were several people at my workplace who also practiced Falun Gong.

In early 1999, I sensed that something would happen after state media broadcast negative propaganda about Falun Gong and announcements were made that party and youth league members were prohibited from practicing. But the full cruelty of the persecution was beyond my imagination.

On July 19, 1999, police harassed and arrested several Falun Gong coordinators in Guangzhou. I joined a group of local practitioners to appeal at the city and provincial petition bureau for their release. The officials told us that the Falun Gong issue had to be handled by the central government, so we decided to go to Beijing to appeal and by chance, were able to obtain train tickets for the next day. The train arrived in Beijing on July 22. We hadn’t heard any news but felt something serious was going on.

The next day we went to peacefully appeal. I was detained and sent to the Fengtai Sports Stadium in a Beijing suburb. That was where I learned about the full ban on Falun Gong. It was a dramatic scene. Tens of thousands of Falun Gong practitioners were sent to the stadium by bus and forced by armed police to line up. No one was allowed to make any noise while the stadium loudspeakers repeated news of the ban in a loop. I felt like I was in some gruesome movie.

After that my life turned completely upside down. I lost my job, had my home searched and property confiscated. I was arrested, sent to a labor camp, and tortured. In July 2000, my mother and I went to Beijing together to appeal for an end to the ban on Falun Gong. We were arrested and sent to detention centers. Guards handcuffed me to a radiator pipe for three days and forced me to tell them my name. I saw practitioners from all over China being tortured by sticks, hanging up, and electric baton shocks; their skin was covered with black bruises and burns.

I was sent to a labor camp for two years. One of the torture methods used there was tying my legs in the double lotus meditation position for 14 hours with my hands behind my back. I eventually was able to stand again, but two other women were permanently disabled because of that method.

My mother Li Naimei was sentenced to the same labor camp and also tortured. She never recovered. In August 2006 she died after her release because of the persecution she suffered there. She was only 63 years old.

Liam O’Neill, Chinese-language high school teacher in New Jersey and local Falun Gong coordinator

I traveled to China in the spring of 1999 to do research for my senior thesis on Buddhism’s revival in the country. I arrived at a Beijing monastery in May and then spent two months living in other monasteries around the country. On July 19, I took an overnight train back to Beijing to spend several more days at the same monastery but they wouldn’t let me stay there. The whole city was on edge, even unaffiliated religious communities, because it was July 20 and Falun Gong had just been banned.

Over my next three frenzied days in Beijing, taxi drivers and restaurant owners would shut down any attempt at conversation about Falun Gong. At one point, I met up with another American college friend, who was studying in China and actually practiced Falun Gong himself. He spoke about showing up at the public meditation site at Tsinghua University and seeing a sign saying Falun Gong was now banned, having people he knew disappear in the middle of the night, and even hearing of soldiers with assault rifles kicking down residential doors and dragging people out of their beds.

I arrived back in the United States on July 24, still trying to understand my last days in Beijing. I would later call them life-changing because, perhaps ironically in terms of what the CCP was trying to achieve, I took up practicing Falun Gong shortly after.

Today, 20 years on, I teach Chinese at a high school in New Jersey and I’m also a volunteer coordinator for a small community of Falun Gong practitioners north of New York City. I’m witness to a constant influx of people arriving in the United States to flee various parts of China, many with horrific stories of arbitrary detention and torture. Nearly all newly arrived practitioners have been touched by the brutality of the persecution via family or close friends. It’s a small microcosm of what is happening in China, but makes you think of the staggering scale of the tragedy.

Chen Pokong, well-known Chinese pro-democracy political commentator, now living in New York

I first heard about Falun Gong around 1993. I took it to be one of the popular Qigong practices at the time. Some people I knew who practiced it told me it was extraordinarily beneficial to their health.

I was already living in exile in the United States in 1999 when I heard that Falun Gong had been banned. My first reaction was that I thought the CCP was being too sensitive to a popular Qigong group. I had been greatly encouraged when seeing Falun Gong practitioners hold a peaceful and silent demonstration for their right to practice around the central government compound of Zhongnanhai on April 25, 1999. When Falun Gong was banned that July, I was surprised and angry. On the one hand, it was not a surprise for me that the CCP would ban a group which was well organized and had their own set of beliefs. On the other hand, it was a surprise for me to realize that the CCP had zero tolerance for even such a peaceful demonstration by a Qigong group. I felt that that more and more Chinese people were being treated as enemies by the CCP, not only we democracy activists.

The CCP’s anti-Falun Gong campaign has split Chinese society again. Part of the Chinese people are suspicious or hostile to people who have their own beliefs. Another part of the Chinese people now dislike or hate the CCP more than ever.

But there is also an inspiring part of the Falun Gong story for me, seeing these practitioners be so well organized and hard working. They have set up their own media outlets, including TV stations, newspapers, and radio stations, as well as websites. These have greatly undermined the CCP’s censorship and repression and encouraged Chinese people all over the world.

Larry Liu, Chinese American and Deputy Director of Government and Advocacy, Falun Dafa Information Center, Washington, D.C.

In the late 1990s, I was a Ph.D. student at Washington University in St. Louis when I started practicing Falun Gong. On July 20, 1999, I was in Missouri on summer break when I heard that Falun Gong had been banned in China. I couldn’t believe it. I thought the Chinese government must have misunderstood us, as we didn’t have any political agenda or motivation. I didn’t expect the ban at all. The Chinese government had said in May and June 1999 that it wouldn’t interfere with people’s Qigong practice. And the April 25 appeal at Zhongnanhai had been peacefully resolved by then Premier Zhu Rongji.

At the time, I was mostly worried about my mother, because she was practicing Falun Gong in China. In late 2000, she went to Tiananmen Square to peacefully protest twice. She was arrested, detained, and tortured. Eventually she was released. Local police threatened that if she didn’t pressure me to stop practicing and being active in the United States, she wouldn’t be able to obtain a passport to visit me. But in 2004, my father, who does not practice Falun Gong, applied for passports for him and my mother and eventually received them. They left China to join me in the United States that summer.

But a young couple that were very close to my mother were not able to escape persecution and lost their lives as a result. Before the ban, they used to mediate with her every morning in the park. The wife died in September 1999 in police custody when she was 27 and her daughter was less than two years old. In 2003, her husband was tortured to death at a labor camp at the age of 31, leaving their 5-year-old daughter an orphan who had to be raised by her grandparents. The persecution of Falun Gong is one of the worst crimes against humanity in the 21st century. History will remember those who have the foresight and courage to speak out against the persecution during this harsh time.

Sarah Cook is a Senior Research Analyst for East Asia at Freedom House, director of its China Media Bulletin, and author of the Battle for China’s Spirit: Religious Revival, Repression, and Resistance under Xi Jinping.