The recent rise of China-Sri Lanka economic relations has been the subject of much discussion, debate, and analysis. Some of these discussions are also rich in misinterpretations, such as common misconceptions about Sri Lanka’s debt obligations to China and the link between that debt and the decision to lease Hambantota port to China for 99 years.

However, one significant part of Sri Lanka-China economic relations has not captured the spotlight: the fast-growing trade relations between two countries during the last decade or so. Similar to other countries’ trade relations with China, the expansion of trade with Sri Lanka was driven by a large influx of Chinese imports, resulting in an expanding trade deficit between the two countries.

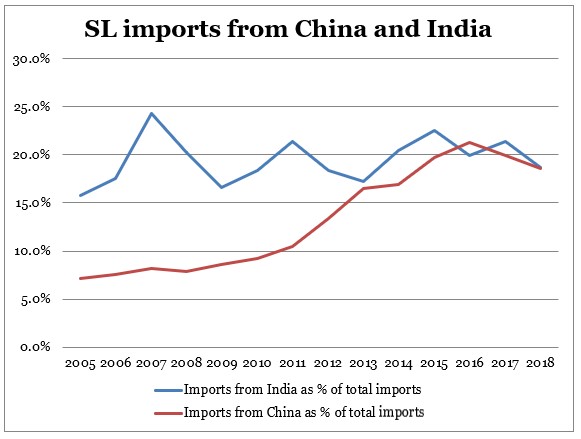

In 2016, China became Sri Lanka’s largest source of imports, surpassing India. However, in subsequent years, the value of Indian imports has marginally exceeded Chinese imports. Although China was unable to remain Sri Lanka’s largest import partner, even its one-off claim to that title indicated the significant growth of Chinese imports and trade relations with Sri Lanka. On top of the noticeable rise of Chinese investments in Sri Lanka, this scenario clearly wouldn’t please India — particularly when China is able to export more to Sri Lanka than India does.

Rise of Chinese Imports

The rise of Chinese imports in Sri Lanka is a relatively recent phenomenon. In 2000, Chinese imports represented only 3.5 percent of Sri Lanka’s total imports; by 2017 that had risen to 20 percent. There was a particularly significant rise in Chinese imports after 2010; from 2011 to 2018 Chinese imports increased by almost four times. India’s story is different. While Chinese imports have not recorded any negative growth years in Sri Lanka since 2010, Indian imports contracted in several years.

Data from Export Development Board, Sri Lanka.

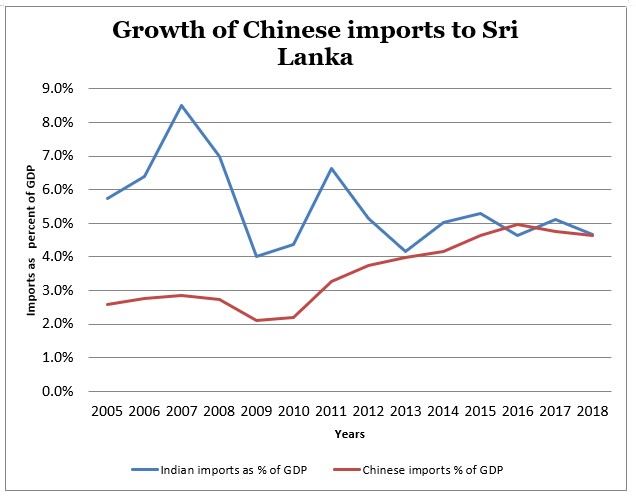

We can get a deeper perspective from the imports-to-GDP ratio, which is considered a better indicator of the trade dynamics of a country. Since 2000, Sri Lanka’s imports-to-GDP ratio has been declining along with the exports-to-GDP ratio. This indicates a clear contraction of trade and a concurrent move toward protectionism, which is a major cause for the economic issues Sri Lanka encounters today. The interesting fact is that Chinese imports to Sri Lanka increased despite Sri Lanka’s overall contraction in international trade and rise of protectionist policies.

Sri Lanka’s imports-to-GDP ratio was 36 percent in 2005; during the same year the Chinese imports-to-GDP ratio was only 2.6 percent. By 2017, the imports-to-GDP ratio had dropped down to 23.8 percent while the Chinese imports-to-GDP ratio had increased to 4.8 percent. This significant increase in Chinese imports came even without China having a free trade agreement (FTA) with Sri Lanka. That means Chinese imports are subjected to normal tariffs, which might be eliminated under an FTA. Contrary to this, India has an FTA with Sri Lanka, the Indo-Sri Lanka Free Trade Agreement (ISFTA), in effect from 2000. Even with that FTA, the Indian imports-to-GDP ratio for Sri Lanka has been fluctuating around 5 percent and has not seen a significant sustained increase since 2005.

Data from the Export Development Board and Central Bank, Sri Lanka.

The FTA Question

Although Sri Lanka currently doesn’t have an FTA with China, there have been discussions about signing such a bilateral deal. Starting in 2014, Sri Lanka and China completed six rounds of negotiations regarding the proposed FTA. The talks ended in 2017 due to disagreements regarding the level of trade liberalization under the proposed FTA. China wanted 90 percent of goods to be tariff free, clearly a scenario Sri Lanka is not comfortable with. However, in June Sri Lanka’s International Trade Ministry stated that during the Sri Lanka visit of China’s vice minister of commerce, Wang Shouwen, the two sides held discussions on restarting their FTA negotiations.

India, on the other hand, signed its very first FTA with Sri Lanka in 1998 (though it came into effect in 2000) and despite several shortcomings ISFTA has helped to expand the trade between two countries. However, neither country is pleased about the level of trade integration achieved through the FTA. In 2017, only around 6 percent of imports from India came through ISFTA (i.e., using the custom duty-free access provided through ISFTA), indicating a heavy underutilization of the free trade agreement. ISFTA has a number of flaws, including the failure to address non-tariff barriers (NTBs) faced by exporters and other duties and levies applied in addition to custom duties. For example, ISFTA does not eliminate all border taxes. Sri Lanka imposes two levies named the Cess Levy and Port and Airport Levy (PAL) on a number of imports and these levies sometimes override the custom duty-free benefit offered through ISFTA. From Sri Lanka’s perspective, more than 60 percent of goods exported to India used the duty-free access provided through ISFTA. Yet export growth to India remains sluggish and exporters have been facing numerous NTBs such as regulation issues in exporting goods to India.

Due to this there had been discussions on expanding the existing FTA and signing what is called an Economic and Technology Cooperation Agreement (ECTA), which would improve the current FTA and include some liberalization of selected services. Eleven rounds of trade negotiations were completed regarding an India-Sri Lanka ETCA. However, negotiations were disrupted due to Colombo’s political and constitutional crisis in October 2018. Since then there has been no progress on ETCA negotiations.

What Led to the Rise of Chinese Imports?

It is both interesting and crucial to look into the causes behind the significant rise of Chinese imports during the last few years. Trade data shows that a significant portion of the import growth has come from electronic items such as mobile phones, monitors, and automatic data processors, and China has been the major source for these products. Nearly 30 percent of Chinese imports in Sri Lanka over the last five years were electronic items. In addition to that, a significant amount of the raw materials used in Sri Lanka’s textile industry — such as fabric and cotton — are also imported from China. However, these are more traditionally imported products; the import growth in the recent past is largely driven by electronics.

Although Chinese imports increased significantly, Sri Lankan exports to China continue to be sluggish, resulting in a continuously expanding trade deficit. In 2005, Sri Lanka’s trade deficit with China amounted to only 2.5 percent of GDP; by 2018 it had risen to 4.4 percent of GDP, accounting nearly for 40 percent of the total trade deficit.

Meanwhile, fuel, vehicles, pharmaceutical products, and steel items make up the majority of Indian imports in Sri Lanka. There are a considerable amount of cotton and fabric imports too, but there hasn’t been a significant growth in imports from India of such goods or electrical items. On the other hand, fuel imports, one of the top Indian imports in Sri Lanka, have not been increasing consistently and in fact saw considerable reductions in several years.

Geopolitical Concern for India

How does India view this scenario of growing Chinese imports to Sri Lanka while Indian imports remain largely stagnant? It is clearly not a huge geopolitical concern, unlike Sri Lanka leasing a port to China or allowing Chinese investors to construct an International Financial City on reclaimed land in Colombo.

However, for India this dynamic is an indication of its failure to strengthen trade ties within the South Asian region, a situation that India does not enjoy. In 2015, China became the top trading partner of Bangladesh and that is likely to be the case for Sri Lanka in near future. This very thought might persuade India to expedite the process of signing the proposed ETCA with Sri Lanka and removing trade barriers to boost bilateral trade.

South Asia, led by India, has performed terribly when it comes to regional trade integration, with intra-regional trade representing just 5 percent of total trade flows. Maybe the rise of Chinese trade relations in South Asia can help change this dismal situation.

Umesh Moramudali is an economic researcher focusing on public debt dynamics in Sri Lanka and international trade. He is currently pursuing an M.Sc in Economics at the University of Warwick.