Two years ago South Korea reached an agreement with China to normalize economic relations and remove the informal economic sanctions Beijing used in an attempt to coerce Seoul into reversing the decision to deploy the Terminal High Altitude Area Defense (THAAD) missile defense system. At the time, there were concerns that South Korea conceded too much to China and that the administration in Seoul might be drawing closer toward Beijing. But two years after the decision was reached it seems to have had limited impact.

THAAD had long been a sore spot between South Korea and China. Soon after the United States and South Korea began seriously discussing the prospect of deploying THAAD to defend against the growing North Korean missile threat, China’s ambassador to Seoul suggested that deployment of the missile defense system could destroy relations between South Korea and China. Once the United States and South Korea formally began deploying THAAD, China wasted little time in taking steps to implement informal sanctions across a range of industries to economically coerce South Korea.

The THAAD system was deployed on a piece of land transferred from Lotte to the South Korean government, putting Lotte at the center of the dispute with China. In time, nearly all of Lotte’s supermarkets in China would be shut down for fire and safety violations. But Lotte wasn’t the only industry targeted by China. South Korean cultural exports such as K-pop and K-dramas had been a mainstay in Chinese popular entertainment. In the aftermath of THAAD exports of new Korean content largely disappeared, co-productions of dramas essentially ended, and Korean artists faced visa restrictions. Beijing also implemented an informal ban on group tourism in South Korea.

Because of the opaqueness of China’s measures it was also harder to know to what extent Hyundai and Kia’s struggles in the Chinese market were related to THAAD or broader market conditions. Similarly, it is unclear if the decision to exclude batteries produced by Samsung SDI and LG Chem from subsidies for electric vehicles was driven by efforts to retaliate against South Korea or Chinese industrial policy to create Chinese champions in the vehicle battery industry.

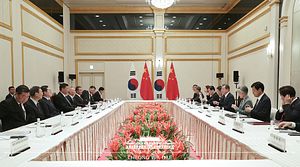

In an effort to relieve the economic strain on targeted industries, the new Moon administration sought a negotiated solution to the impasse in the fall of 2017. The agreement with China called for the resumption of normal economic relations and a commitment to “three noes” by South Korea – no additional deployment of THAAD batteries, no South Korean integration into a U.S. led regional missile defense system, and no trilateral alliance with the United States and Japan.

While criticized at the time for undermining South Korea’s national defense and providing Beijing a “strategic reward,” the South Korean government promised nothing of substance to China. There were no THAAD batteries available to be deployed to the Korean peninsula at the time, and the idea of South Korea joining an integrated missile defense system – much less a trilateral alliance — wasn’t a real option on the table at the time either (even if the United States would like to see South Korea eventually move in that direction over time). The “three noes” were also established South Korean positions prior to the agreement. South Korea emphasized that “Seoul has consistently made clear [to China that] any issues that can restrict our security sovereignty would never be subject to the negotiation.”

If South Korea gave up little to China in normalizing relations, it perhaps received less than it expected from China as well. Because there are no sanctions to rescind, there is a degree of ambiguity that makes it harder to know when China fully “normalized” relations with South Korea.

Despite the 2017 agreement to repair ties, Lotte has largely left the Chinese market as a result of the sanctions and preexisting business pressures. Beijing didn’t remove the sanctions on Lotte until earlier this year and is also considering closing its beverage and confectionery factories in China as well. All told, in the 18 months from January of 2017, Lotte has suffered losses of $1.7 billion in China.

At the height of the THAAD dispute Chinese tourism to South Korea dropped by nearly half as Beijing prohibited group tours to South Korea. While the resumption of normal relations has seen an uptick in Chinese tourists in South Korea, through September of this year the number of Chinese tourists visiting South Korea is still down 1.9 million compared to the same period in 2016. Based on the average spending of group tourists at the time, the South Korean tourism industry may have lost upwards of $24 billion over the last two and a half years.

The damage for K-pop ended up being less, but partially because agencies were able to tap into Chinese stars. The dispute may also have helped spur some of the growth we’ve seen of K-pop in other countries as it forced the industry to look to other markets.

The effects of THAAD also bled into other areas of South Korea’s relationship with China. While the primary source of pressure on South Korea was economic, China also suspended all high level defense dialogues with Seoul. Despite agreeing to normalize relations, the strategic defense dialogue only resumed in October of this year.

Though South Korea’s “three noes” may not have had a significant impact on Seoul’s security policy and brought only limited benefits to the South Korean economy, the issue did expose an aspect of the alliance that could be exploited at a later date – the absence of U.S. support for allies under economic coercion. Whether the United States was unable or unwilling to intervene to limit China’s economic coercion, its failure to do so exposed a gap in the alliance that needs to be addressed. That may be the real legacy of the “three noes.”