Late last month, public security agencies and a school in Hebei Province “seriously criticized” a 15-year-old student for accessing blocked websites and browsing information that was deemed “antagonistic toward China.” A few days earlier, another Chinese netizen had reported that his account on Tencent’s social media platform WeChat had been suspended for “spreading malicious rumors” after he posted a comment about Winnie the Pooh, whose likeness is often used to mock President Xi Jinping. It will soon be even easier for authorities to track down such individuals: as of December 1, all telecommunications companies will be required to obtain facial scans of new internet or mobile phone users as part of the real-name registration process.

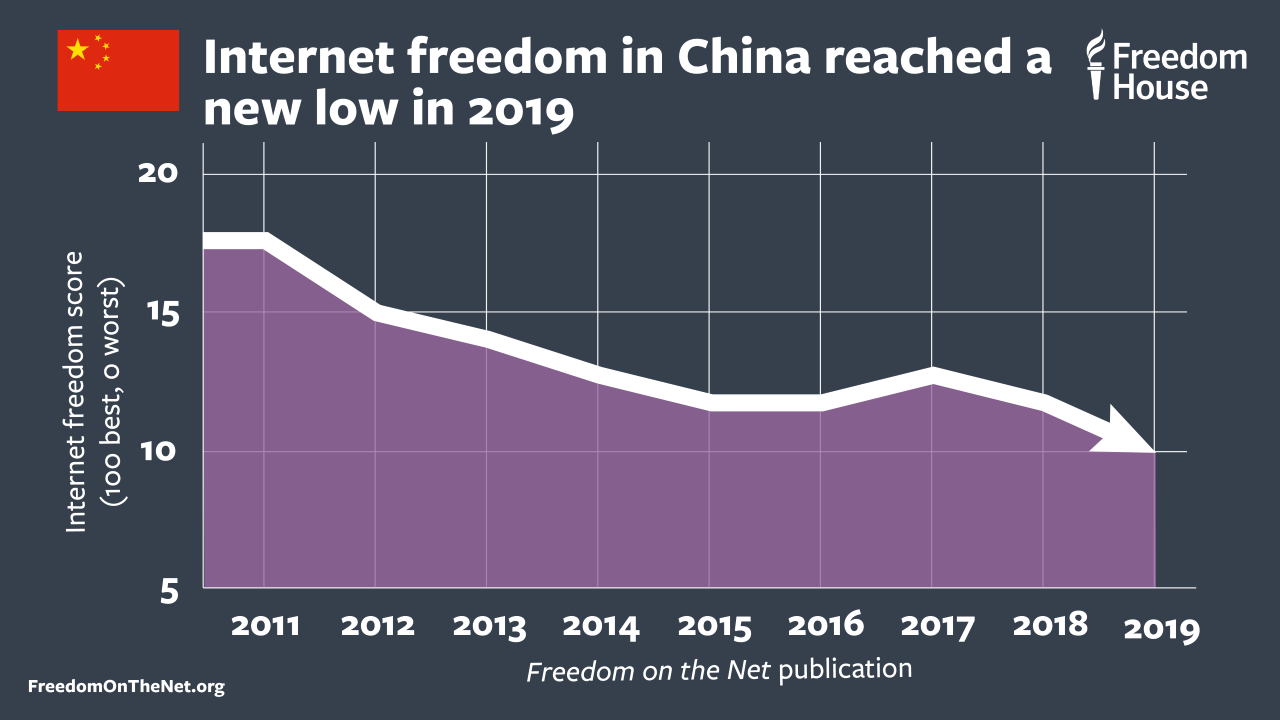

These are just a few recent examples of the daunting growth in restrictions on expression, privacy, and access to information in China. Indeed, the newly released edition of Freedom House’s annual global assessment of internet freedom, Freedom on the Net, identified the Chinese government as the world’s worst abuser of internet freedom for the fourth consecutive year. But even by China’s own poor track record, the past year stood out, as the country’s score reached its lowest point since the inception of the report a decade ago.

Extreme Censorship and Penalties for Once-Tolerated Activities

Driven by official paranoia surrounding the 30th anniversary of the Tiananmen Square massacre, persistent antigovernment protests in Hong Kong, and an ongoing trade war with the United States, information controls in China reached exceptional levels over the past year. The scale of content removals, website closures, and social media account deletions expanded, affecting tens of thousands of individual users and institutional content providers. Platforms focused on apolitical topics, including entertainment, dating, and celebrity gossip applications, faced new restrictions, particularly on their real-time communication features. Information on subjects like economic news that have traditionally been given freer rein became more systematically and permanently censored.

Chinese citizens’ risk of being detained or imprisoned for accessing or sharing information online has increased considerably in recent years. During the past year alone, several new categories of individuals were targeted with legal and extralegal reprisals for their online activity. These included users of Twitter, which is blocked in China but still accessible via circumvention tools such as virtual private networks (VPNs). Numerous Twitter users were harassed, detained, interrogated by police, and forced to delete their past posts. Some users and sellers of VPNs faced similar reprisals, although on a smaller scale.

Ordinary users of WeChat increasingly faced detention and prosecution. Among others who were jailed during 2019, the moderator of a popular WeChat account that shared news from outside China was sentenced in July to two years in prison; a professor from Guangdong Province was jailed for three and a half years after posting images related to the banned Falun Gong spiritual movement; and a 22-year-old Tibetan monk from Sichuan Province was arrested for expressing concern over Beijing’s policies that are reducing use of the Tibetan language. Several activists who operated websites about civil society and human rights issues also faced pretrial detention and long prison sentences. The most prominent was Huang Qi, founder of the human rights website 64 Tianwang, who was sentenced in July to 12 years in prison for “intentionally leaking state secrets.”

Muslim minorities in the Xinjiang region increasingly faced severe penalties and long-term detention for mundane online activities like communicating with relatives who live abroad. Erpat Ablekrem, a 24-year-old aspiring professional soccer player, was sent to a reeducation camp in January 2019 for using WeChat to contact family members who had fled the country. Rapid advances in surveillance technology and greater police access to user data have helped facilitate this rise in arrests and prosecutions. In some instances, tools that were first deployed by police in Xinjiang have now spread to other parts of China, such as hand-held devices used for extracting data from mobile phones.

Impact on User Communication

In response to the escalation of real-world reprisals and legal penalties for online commentary, self-censorship has become more pervasive. The risk of losing one’s personal WeChat account is a particularly strong deterrent, since the multifaceted application — used for everything from banking to ordering food — is now regarded as essential to everyday life in China.

The space for online mobilization has also narrowed. The effects of the Chinese government’s multiyear crackdown on civil society and nongovernmental organizations are visible in the online sphere, as previously outspoken activists have gone silent following arrests or the closure of their social media accounts.

Several platforms that still provided alternative means of communication on routinely censored topics — such as video-sharing, live-streaming, and blockchain applications — faced new restrictions during the year, indicating that the authorities were determined to plug gaps in the system. For example, blockchain platforms were required to enforce real-name registration and censor their content, and artificial intelligence was deployed to screen images for banned material.

Global Implications

Foreigners visiting China should not expect to be exempt from the government’s ever-expanding web of surveillance and censorship. Recent Freedom House research on police use of advanced databases to track “key individuals” throughout China found that foreigners are one of the targeted populations. At least one foreign journalist reporting from China said he was barred from his WeChat account for “spreading rumors” about the Tiananmen Square massacre. He had to admit to the offense and provide a face scan before access could be restored. Ongoing restrictions on VPNs and implementation of the facial-scan requirement for SIM card registration may also disproportionately affect foreign visitors to the country.

Meanwhile, international companies and investors must grapple with the increasing censorship of economic news, U.S. government sanctions on Chinese technology firms linked to human rights abuses in Xinjiang, and the prominent role of social media giants like Tencent in helping to detect and penalize users for engaging in legitimate political, religious, or simply humorous speech. Foreign firms like Apple, Microsoft, and LinkedIn have already complied with government censorship in China, and they could be forced to play a part in user arrests as well.

Even as it increases internet controls at home, the Chinese government and affiliated private companies are affecting internet freedom in other countries around the world. In the 2018 edition of Freedom on the Net, Freedom House found that 36 out of 65 countries under study had sent personnel to China for training on new media or information management, while 18 had purchased artificial intelligence–enabled surveillance systems. New research published in 2019 by the Open Technology Fund shows that both fields of activity have continued to expand, with Chinese-made internet control equipment and official training reaching more than 70 countries.

The 2019 edition of Freedom on the Net noted that China has emerged as a leader in developing, employing, and exporting automated tools for mass surveillance of social media. The Chinese firm Knowlesys, for example, is planning to provide live demonstrations at an upcoming trade show in Dubai on how to “monitor your targets’ messages, profiles, locations, behaviors, relationships, and more,” and how to “monitor public opinion” for elections. Mass surveillance of social media was identified in 40 of the 65 countries assessed in 2019, though not all employed Chinese technology.

This year featured a series of especially sensitive anniversaries that motivated the escalation in censorship and surveillance in China, but there is no reason to believe that the new restrictions will be rolled back. On the contrary, the leadership appears determined to ratchet up its repression indefinitely as it pursues the impossible goal of ideological conformity and social control in a globally engaged nation of 1.4 billion people. In fact, it is increasingly obvious that Beijing’s efforts are, by necessity, global in scope, and that the rest of the world will have to choose between resistance and complicity.

Sarah Cook is a senior research analyst for China, Hong Kong and Taiwan at Freedom House and director of its China Media Bulletin. Mai Truong is Freedom House’s research director for strategy and management.