The longstanding desire of the Sikh community to be able to visit one of their holiest sites, the last resting place of Guru Nanak Dev, in Pakistan has been fulfilled at last. Just four kilometers from the international border and visible on clear days, the Sikh shrine was awarded to Pakistan at the time of British India’s Partition in 1947.

It is indeed a pivotal moment in the history of India-Pakistan relations, which has received considerable public attention. Even the U.S. State Department underlined its importance when it gave a statement on the Kartarpur Corridor on the day of its opening. However, Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s expression of gratitude to Pakistani Prime Minister Imran Khan for honoring the feelings of Indians on Kartarpur was baffling and contradictory.

Optimists would argue that when virtually every avenue of people-to-people contact between the two hostile neighbors has been closed, the opening of the Kartarpur corridor should be seen as the most positive development.

But pessimists would counter this optimism by arguing that trust between the main political actors – as well as the experience of sharing common values and goals – must exist prior to the institutionalization of the process of building trust. They would point to the fact that though Khan offered an olive branch of peace to Modi, he still could not stop himself from reiterating Pakistan’s long-held position on Kashmir when he raised the issue of alleged mistreatment of Kashmiris by India. Given his several domestic challenges on both economic and political fronts, Imran Khan has very few options but to raise the pitch on Kashmir, but there should be no doubt that Pakistan will not lose any opportunity to embarrass India on the issue.

Meanwhile, Modi thanked the Pakistani workers who had built the corridor in record time. But his attempts to equate the opening of the Kartarpur Corridor with the fall of the Berlin Wall are not supported by facts on the ground, and therefore lack substance. Three decades ago, the fall of the Berlin Wall signified the end of the arbitrary division between East Germany and West Germany. But it also signaled the end of the Cold War; the two superpowers were locked in a bitter post-World War II rivalry, and the disappearance of the Berlin Wall ensured that only one remained. Since the Cold War between India and Pakistan is yet to be terminated, it is not clear if Modi meant the territorial disintegration of India’s bitterest enemy by his Berlin Wall analogy.

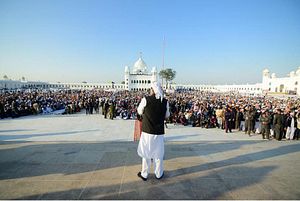

Modi inaugurated the Indian side of the corridor at Dera Baba Nanak in Gurdaspur but his absence from the main ceremony at Darbar Sahib Gurdwara in Kartarpur was deliberate. His preference to remain on the India side of the Redcliff Line and let the Indian delegation — including Punjab Chief Minister Amarinder Singh and former Indian Prime Minister Manmohan Singh — be on the other side belies the hope of the Kartarpur Corridor being a breakthrough in India and Pakistan’s fractured relationship. In a recent public address, India’s external affairs minister has already ruled out the possibility of a dialogue with Pakistan, which “has built an industry of terror.”

Despite frequent tensions between the two neighbors, particularly following India’s abrupt decision to abrogate Article 370 of Indian Constitution, both India and India signed the agreement to operationalize the corridor to allow Indian Sikhs to visit the Darbar Sahib in Pakistan. But India had very few options. India was not in a position to resist Pakistan’s offer on Kartarpur as the Indian government does not wish to be seen disregarding the religious sentiments of the Sikh community.

In addition, Pakistan’s hidden agenda on opening the Kartarpur corridor are not so hidden. Though Pakistan is busy projecting this event as a historic confidence-building measure aimed at winning hearts and minds, it, however, cannot hide its real intentions. Even the civilian and the military leadership, despite the rhetoric of harmonious civil-military bonhomie, have often spoken in different voices on many occasions regarding the corridor. However, the most important worry, downplayed by the optimists, pertains to the Khalistan movement, which was crushed by India’s counterinsurgency campaign two decades ago. An official promotional video released by Pakistan on the Kartarpur Corridor featured Sikh separatists, in particular, the perpetrator of the reign of terror in Punjab in the early 1980s, Jarnail Singh Bhindranwale and his military adviser Shabeg Singh, who were eventually killed during the Operation Blue Star to flush out terrorists from the Golden Temple. This exposes Pakistan’s plan to use the controversial imagery in creating radical Sikh groups in Indian Punjab. Before this, Pakistan had also appointed an anti-India Khalistani separatist – also a close aide of terrorist Hafiz Saeed – in a committee on the Kartarpur Corridor project. This move was strongly opposed by the Modi government.

For proud Indian Sikhs, the very suggestion that they can fall for Pakistan-sponsored propaganda will be offensive. Given the institutionalized structures of Sikh politics in Punjab, the mass mobilization of Sikhs on the issue of Khalistan seems a very remote possibility without active backing from the dominant Sikh political actors such as the Shiromani Gurdwara Prabandhak Committee, Akal Takht, and Akali Dal, none of which has any appetite for a confrontation with the government in New Delhi. But the concerns among India’s security and intelligence agencies cannot be completely brushed aside regarding the exploitation of Kartarpur’s opening by Pakistan’s security establishment to revive the Khalistan movement. The seizure of several drones along the western border in recent months is cited as a testimony to this strategy.

Modi has always surprised his supporters and detractors alike with his bold and unorthodox moves. His politically risky trip to Lahore to meet his Pakistani counterpart, Nawaz Sharif, in December 2015 was truly historic and statesmanlike. But many observers have pointed out that New Delhi made the mistake of neglecting to get the Pakistan army on board, and that had instant repercussions in the form of the Pathankot airbase attack in January 2016. It has been a different picture this time, as the Pakistan Army is fully on board. In fact, it was the Pakistan Army that undertook the Kartarpur project and completed it well before schedule. But there are apprehensions that the entire army may not be on board; there are speculations that many generals junior to Qamar Javed Bajwa are annoyed with his three-year service extension.

Keeping this background in view, those in Pakistan who entertain the hope that this “good gesture” from the Pakistani government might lead to another, including the possibility of Modi relaxing his aggressive posture on Pakistan-sponsored terrorism, seem to be living in a fool’s paradise. New Delhi will not reverse its decision on Kashmir in the absence of unbearable arm-twisting by Pakistan’s international backers. Given the global geopolitical scenario at present, this is unlikely to happen without corresponding elimination of terrorism in the volatile valley.

Both optimists and pessimists have their shortcomings, since nobody is sure where the truth lies. In the labyrinthine politics of India-Pakistan relations, it is nearly impossible to predict what happens next. Over the past seven decades since the Partition, India and Pakistan have witnessed many ups and downs, but the current phase is probably the worst in their tortuous ties. If any future terrorist incident in India is linked with non-state actors inside Pakistan, it will have repercussions for the Kartarpur Corridor. An alternative scenario for Pakistan is to give up its obsession on Kashmir. There are many sensible voices in Pakistan who advocate such an approach to ensure the betterment of their own country. But neither the military nor the radical Islamist groups favor such an approach to improve relations with India.

Vinay Kaura is an Assistant Professor in the Department of International Affairs and Security Studies, Sardar Patel University of Police, Security and Criminal Justice, Rajasthan.