On December 2, Donald Trump announced on Twitter that the United States would impose steel and aluminum tariffs on Argentina and Brazil in response to what he described as the countries’ “massive devaluation of their currencies, which is not good for our farmers.” By doing so, Trump is pushing Brazil and Argentina toward China. That is particularly true for president-elect Alberto Fernández, who will be inaugurated as Argentina’s president on December 10.

A new wave of populist governments with autocratic tendencies has come into power in Latin America, ending the left-leaning “pink tide” that swept across the region in the early 2000s. These new governments cast shadows over China’s comprehensive strategic partnerships in the region. After years of high commodity prices that benefited many Latin American countries’ raw material export sectors, the amount of Chinese FDI decreased by a third in 2018.

As a self-declared “Tariff Man,” Trump’s most recent decision may turn out to have a silver lining for China’s relations with Latin America in general, and with Argentina in particular.

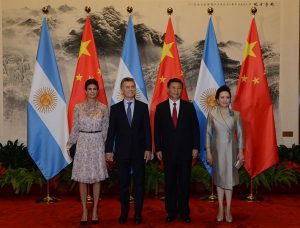

Argentina has a comprehensive strategic partnership with China, a diplomatic status the latter confers on just a few countries. The relationship between the two has continued to develop since the government of former President Cristina Fernández de Kirchner, under whom more than 20 treaties and investment projects were agreed. Despite initial doubts about Argentina’s relationship with China, outgoing President Mauricio Macri has maintained the close ties established by his predecessor.

Despite increasing tensions between Washington and Beijing, Macri built friendly relationships with both powers. He was welcomed with open arms at international fora like the G-20 and the World Economic Forum in Davos. In May 2017, Macri attended the Belt and Road Forum in Beijing. Chinese President Xi Jinping welcomed him by proclaiming that “Latin America is the natural extension of the 21st century Maritime Silk Road” while applauding Argentina’s support and participation in the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI). As of 2018 there were over 50 Chinese companies operating in Argentina, including Huawei, ZTE, Shanghai SVA, China TCL Group, Nanjing Jincheng, the Industrial and Commercial Bank of China (ICBC) and the People’s Bank of China.

China and Argentina have a number of joint development projects underway as part of the BRI, which are helping to energize local economies in various provinces. For instance, Chinese companies are helping construct South America’s largest solar farm in the northwestern province of Jujuy and wind farms in the provinces of Buenos Aires and Chubut, with an eye to boosting renewable energy and contributing to combating climate change. As a sign of the importance of these economic ties, Macri, who at one point seemed about to pull the plug on Chinese-financed power plants, had little choice but to allow construction to go forward while he campaigned for re-election in October.

The RMB has proven to be a useful tool in the relationship. Argentina has long been in the grips of a financial crisis that has all but locked it out of credit markets and paralyzed investment. Last December, Argentina’s central bank signed a deal with its Chinese counterpart to expand a currency swap program by $8 billion, bringing the total swap amount to $18.7 billion. The agreement is an extension of a swap signed between the two countries in July 2017. The less money the incoming Fernández government can borrow from international markets, the more RMB might be internationalized in Argentina.

When it comes to finances, China has advantages of “patient capital.” According to Justin Yifu Lin and Yan Wang, Honorary Dean and senior fellow of the National School of Development at Peking University, there are three rationales behind the BRI. First, China has demonstrated comparative advantages in building infrastructure, including hydroelectric power stations, highways, ports, railways, and telecom networks. Second, China has constructed many industrial parks and special economic zones overseas, with many successful experiences. Third, Lin and Wang argue that a new concept of “patient capital” can be utilized to finance the BRI and fill infrastructure gaps.

Before the G-20 meeting in 2018, Argentina’s infrastructure funding shortage was estimated at $26 billion, which equated to over one-fifth of their total government spending in 2017. What’s more, the shortage is expected to rise to $358 billion by the year 2040. If new government cannot bridge the gap, it will sustain a negative spiral for the country’s economy as well as its people. The more infrastructure Argentina needs to build, the more important and effective China’s “patient capital” becomes.

With the BRI being expanded to Latin America and Washington appearing content to cede leadership in the region to China, the only sure thing is that Argentina faces great economic uncertainty in the short run, with long-run outcomes hanging in the balance. Argentina may provide a testing ground for China’s alternative model for development, which is very different from the Western model.

Antonio C. Hsiang is Professor and Director of the Center for Latin American Economy and Trade Studies, at Chihlee University of Technology.