On December 12, 2019, Malaysia warmed up another round of the diplomatic row in the South China Sea (SCS) by making a new submission on an extended continental shelf (ECS) beyond 200 nautical miles from the baselines from which the breadth of the territorial sea is measured to the United Nations Commission on the Limits of the Continental Shelf (CLCS). It was an individual partial submission after the Vietnam-Malaysia joint submission of an ECS beyond 200 nm in 2009.

Malaysia’s move surprised regional watchers. The key question is why Malaysia undertook this measure at this time. The submission was handed over at the end of the 51st session of the CLCS. It is clear that interest in clarifying Malaysia’s claims is not the main motivation.

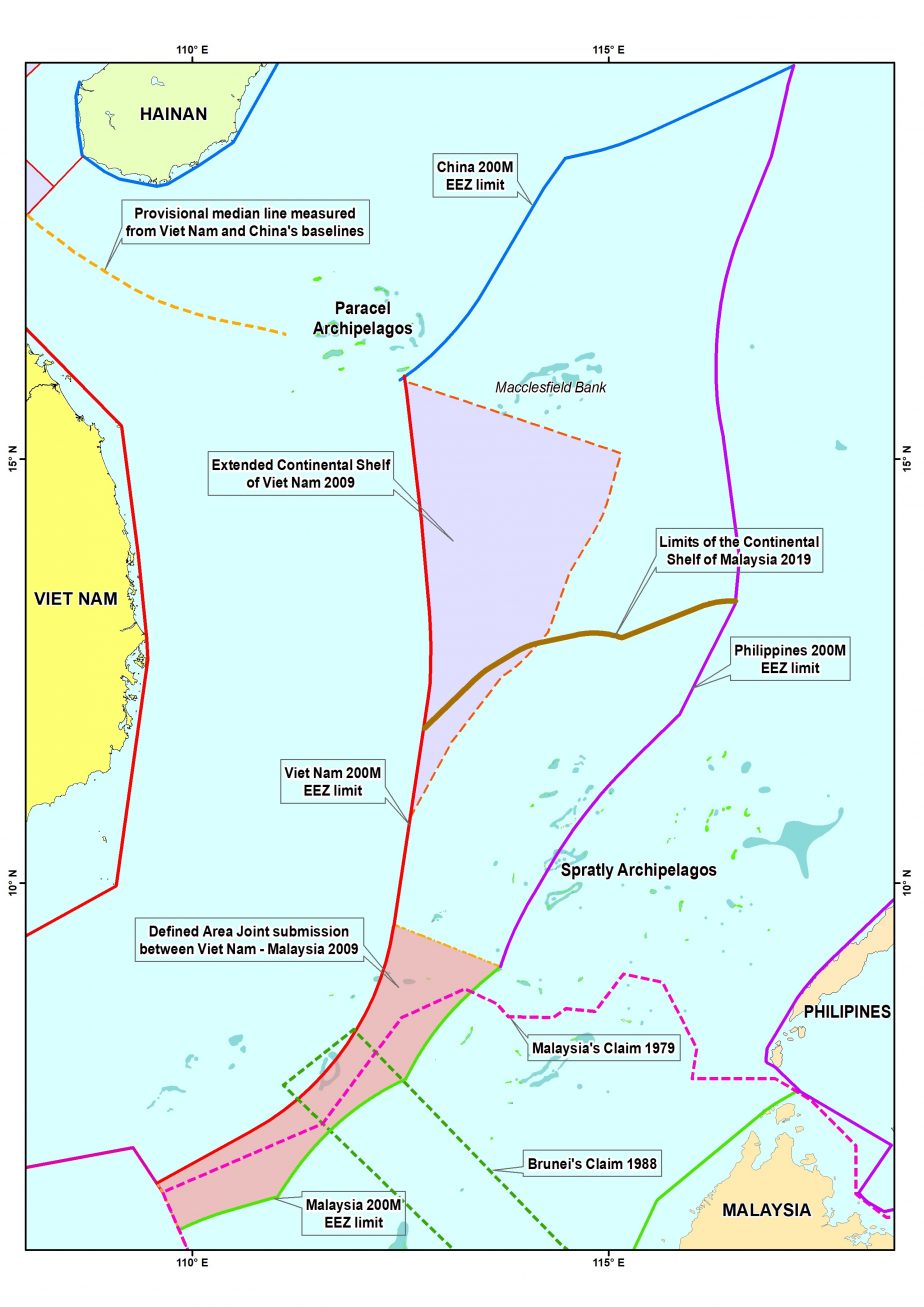

In the SCS region, Indonesia was the first country to submit information on the outer limits of the continental shelf beyond 200 nm in the northwest area of Sumatra Island on June 16, 2008. However, the turning point for the race for an ECS was the Vietnam-Malaysia joint submission relating to an area in the south of the SCS, which was made a couple of days before the deadline of May 13, 2009 fixed by UNCLOS and related agreements. At the same time, Vietnam also lodged a partial submission on the northeast area of the South China Sea (VN-N) to the CLCS. Both submissions dismissed the possibility of continental shelves generated by the insular features in the Spratly and Paracels.

China protested both submissions. The “nine-dash line” map attached with its diplomatic notes on May 8, 2009, is purposed to negate any existence of a continental shelf beyond 200 nm in the SCS. Also, the Chinese claim a continental shelf for all features in the center of the SCS.

(Brunei and the Philippines reserved their rights to make submissions in areas of the SCS in accordance with the requirements of Article 76 of the Convention and with the Rules of Procedure and the Scientific and Technical Guidelines of the Commission.)

The contradiction of the two approaches relating to the existence of the ECS beyond 200 nm has prevented the Commission from considering the two above-mentioned submissions since 2009. However, the Tribunal Award of July 12, 2016, over the case of the Philippines vs. China rules all features in the Spratlys are not islands in the legal sense, which generated the possibility of the existence of high seas and seabed area (considered the “common heritage of mankind”) in the center of the SCS.

Through its latest submission, Malaysia has killed a couple of birds with one stone. First, it extends the continental shelf claim illustrated in the Malaysian Department of Mapping and Survey’s 1979 Map in both the southern and northern parts of the SCS to gain almost twice as much as continental shelf compared to the 1979 claim.

Through its latest submission, Malaysia has killed a couple of birds with one stone. First, it extends the continental shelf claim illustrated in the Malaysian Department of Mapping and Survey’s 1979 Map in both the southern and northern parts of the SCS to gain almost twice as much as continental shelf compared to the 1979 claim.

Second, it implicitly shows support for the 2016 Tribunal Award that qualified all insular features of the Spratlys archipelago as having only 12 nm territorial sea and no claim to generating their own exclusive economic zones and continental shelves. Interestingly, the cover page of this Partial Submission dates back to 2017; perhaps that file was prepared not long after the judgment.

Third, the submission indirectly rejects the validity of China’s nine-dash line claim, even though Malaysia was not party to the Philippines’ SCS case. In its note dated December 12, 2019, protesting the Malaysian submission, China repeated its claim to have an exclusive economic zone and continental shelf based on Nanhai Zhudao (the island groups China claims in the region) and its historic rights in the SCS.

Fourth, the submissions promotes a similar application of the tribunal’s decision to the Paracels insular features in declaring that the “subject of this Partial Submission is not located in an area which has any land or maritime dispute between Malaysia and any other coastal State.”

Fifth, it prompts other concerned states to talk with Malaysia about delimiting possibly overlapping areas. The submission acknowledges that “there are areas of possible overlapping entitlements in respect of the continental shelf beyond 200 nm of the area of the subject of this Partial Submission.” In this vein, the Philippines may join with Vietnam and Malaysia in submitting tripartite submission on the ECS beyond 200 nm in the future.

Sixth, the submission, done before the end of the Code of Conduct negotiations, allows Malaysia to avoid restrictions in the final COC (if any). It also assists Malaysia in seeking advantages in negotiations related to the SCS.

Last but not least, it also encourages the CLCS to reconsider the Vietnam-Malaysia joint submission since the grounds on which China and the Philippines based their protests were removed by the Tribunal Award of 2016. To be exact, the nine-dash line was ruled not legally valid and the features in the Spratlys are not qualified as islands. In other word, the Malaysian submission raises a question about the relationship between the work of the CLCS and juridical decisions. Theoretically, the Commission has no jurisdiction to make recommendations to coastal states on matters related to the establishment of the outer limits of their continental shelf beyond 200 nm if protests from other states exist. However, those protests must be based on firm legal grounds. The race to delineate ECS limits beyond 200 nm would affect also the ongoing negotiation on the Code of Conduct between China and ASEAN because the SCS could be not qualified as a semi-enclosed sea due to the existence of the High Sea in its center.

Malaysia seemingly made an error in mapping its new ECS limits, which overlap a portion in the southwest of the VN-N ECS claim in 2009. The divergence can be explained by the different methods that parties applied for calculating the outer limits of the continental shelf beyond 200 nm. Vietnam delineated the outer limits of its extended continental shelf in the North Area by application of both the 1 percent sediment thickness formula (the Gardiner formula) and the Foot of the Slope (FOS) + 60 M formula (the Hedberg formula) while Malaysia only used the latter. Malaysia ignores also the possibility of a Vietnamese claim for an ECS beyond 200 nm from its central coast and the Philippine claim from its archipelagic baselines. However, the submission by Malaysia represents a positive step forward for coastal states in the SCS to clarify their claims and seriously discuss maritime delimitation in accordance with UNCLOS and the interpretation of its article 121 (3) by the 2016 Tribunal Award.

Nguyen Hong Thao is an Associate Professor of the National University of Hanoi and Diplomatic Academy of Vietnam.