The fate of Taiwan’s upcoming elections changed on November 13. Until that day, the Chinese Nationalist Party (Kuomintang or KMT) had a strong lead ahead of the ruling Democratic Progressive Party (DPP) in the Legislative Yuan polls. Even with six months of constant protest in Hong Kong and a failing presidential candidate (Han Kuo-yu), as a party the KMT was still polling higher than the pro-Taiwan DPP.

A week later, the KMT and DPP’s positions began to switch. The KMT fell in the polls and today continues to drop. The DPP’s odds of maintaining their legislative majority drastically increased because of a feature of Taiwanese politics that many are not familiar with: the party list.

What Is the Party List?

Taiwan’s Legislative Yuan has three distinct groups of legislators. First are district representatives that come from specific districts. Next are six reserved seats for indigenous Taiwanese. Finally, 34 of the 113 seats are reserved for proportional representation (PR). When Taiwanese voters go to the booths, one of their votes goes to whatever party they wish to support, regardless of where they live or who runs in their district. Depending on what percentage of votes each party gets, they get a proportional number of those 34 reserved seats for their party. For example, if the KMT and DPP each get 50 percent of the PR votes, each party would get an additional 17 legislators.

Each party internally determines which legislators will get those PR seats. Once negotiated, parties release their lists with a ranked order of who would get the first, second, third, etc. seat. Since the DPP and KMT are the two largest parties, it’s safe to assume they are guaranteed 10 additional legislators from the party list, which makes the first 10 spots on party lists extremely important — they are certainly going to be in office regardless of their popularity or political stances.

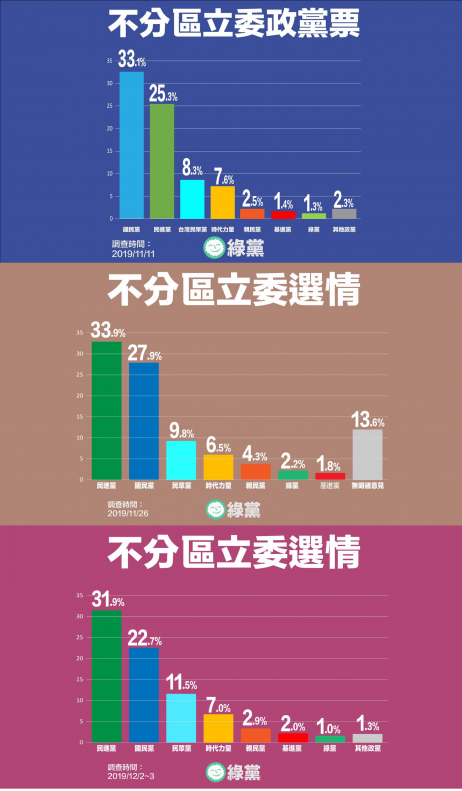

Three party polls, one (in blue) conducted days before the party lists were released, one (in brown) two weeks after, and one (in pink) three weeks after. KMT support is shown in blue; DPP support in green. Source: Taiwan Green Party.

What Happened?

In the week after November 13, the KMT and DPP both released their party lists.

The KMT stacked their list full of unabashed pro-unification politicians. For example, former legislator Chiu Yi (邱毅), an advocate of unification who has openly stated that supporters of Taiwanese independence should be “decapitated” once unification is achieved, was number eight on their original list.

The KMT likely figured they could get away with a highly pro-unification party list. In years past, the party list has not been particularly important, and was not a feature of elections that Taiwanese voters paid particular attention to. But this year is different. According to “Who Governs?” a Taiwanese political science blog, Google results within a two-week time span after the party list announcement showed interest in the party lists had reached an all-time high. The number of people of searching “party list legislator” (不分區立委) was three times more than in 2016 and 10 times more than 2012.

The Taiwanese people noticed the KMT list, and people were outraged. Ever since its release date, the KMT’s stock has plummeted.

Anger against the KMT’s blatantly slanted party list was so bad that the KMT withdrew the list and released a new one a few days later. Although Chiu Yi is no longer on the list, other controversial blatantly pro-CCP politicians remained.

For example, Wu Sz-huai (吳斯懷) is number four on their list. Wu visited China to listen to a speech of Xi Jinping’s in 2016, and is a leader of the “800 Heroes” anti-pension reform group, known for its violent protests against the Tsai administration’s efforts to reform the pension system used as a reward for political loyalty to members of the military, public servants, and teachers in authoritarian times.

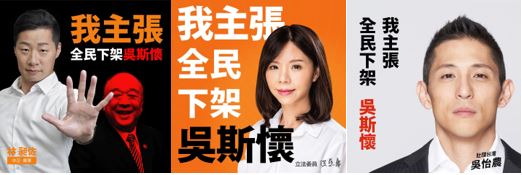

Wu and the KMT’s party list has since become one of the DPP’s new key talking points during campaign rallies. Wu and the rest of the list give the DPP an easy way to talk about how the KMT politicians like Wu present a major threat to Taiwanese national security. One DPP candidate, Enoch Wu, launched a viral campaign calling on voters to not vote for the KMT in sufficient numbers so that Wu does not make it into the legislature. Since the campaign started, DPP and DPP-affiliated candidates have all begun using the phrase “I advocate for all of society to take down Wu Sz-huai.”

The Effects of the Party List

It is worth asking: did Hong Kong have anything to do with the KMT’s drop in popularity? Although Hong Kong is a major talking point this election, the effect it actually has on voter opinion is overstated. The most obvious data point to look at is how incredibly well the KMT was polling before the party lists were released.

Despite six months of protests, Han’s failed political campaign, and the DPP’s constant invoking of the Hong Kong protests, the KMT was still polling better than the DPP. It was only after the party lists were released that the KMT’s numbers dropped. No amount of escalation in Hong Kong or political speeches made by Tsai or the DPP was enough to hurt the KMT’s polling numbers. Only when the KMT tried to sneak blatantly pro-unification politicians through their party list did Taiwanese voters become outraged at the KMT.

Campaign ads with the slogan: “I advocate for all of society to take down Wu Sz-huai.”

What does this say about the status of Taiwan’s democracy? The news is bleak these days, with stories of CCP infiltration into Taiwan’s democracy or the constant information war Taiwan is fighting to keep its news clean and free of fraud. People often think Taiwan’s democracy is weakening, or that Taiwanese citizens do not care enough about the health of their political system.

But the amount of outrage shown around the party list — a subject that in elections past was hardly discussed — shows that Taiwanese voters care about their democracy and are actively engaged in the electoral process. Although the KMT’s party list catastrophe may be seen as a sign at how easily pro-CCP politicians can infiltrate Taiwan’s democracy, it is also a story of how Taiwanese citizens are still willing to get outraged over dirty politics.

More broadly, the KMT’s party list suggests the party’s lack of long-term viability, in that the party seems unable to produce up-and-coming younger candidates the way that the DPP is able to. For example, one notes, legislator Jason Hsu, was left off of the party list, effectively barring him political office. Hsu, 41, became well-known in the last few years because he was not only one of the KMT’s younger legislators, but took stances at odds with the rest of the party such as supporting gay marriage. This is likely the reason why Hsu was not put on the party list.

The KMT party list also suggests that the party leadership remains out of step with public opinion regarding issues regarding Taiwanese sovereignty. The independence/unification question remains the most salient issue in Taiwanese politics, but the KMT seems to have chosen to fight a losing battle on this front, with a continued lack of interest in localization.

Although the DPP is in a much stronger position than they were a month ago, their ability to retake the Legislative Yuan is hardly a sure thing. With a month to go until the election, the KMT still has a chance to regain lost ground. More than a few of the DPP’s contested seats that they won in 2016 will not be easily retaken in 2020. There is still a real possibility they will not maintain their majority. The party list fiasco, however, has hurt the KMT in an unprecedented way that they were unprepared for. Although the DPP still has an incredibly tough battle for the Legislative Yuan, their election just got a bit easier.

Lev Nachman is a Fulbright research fellow in Taiwan and a Ph.D. candidate in political science at the University of California Irvine.

Brian Hioe is one of the founding editors of New Bloom, an online magazine covering activism and youth politics in Taiwan founded in 2014 in the wake of the Sunflower Movement. He has an MA in East Asian Languages and Cultures from Columbia University and was Democracy and Human Rights Service Fellow at the Taiwan Foundation for Democracy from 2017 to 2018.