During the Chinese Communist Party’s (CCP’s) 19th national congress, General Secretary Xi Jinping remarked, “We will improve our capacity for engaging in international communication so as to tell China’s stories well, present a true, multi-dimensional, and panoramic view of China, and enhance our country’s cultural soft power.” China has poured billions into reaching out to international, mostly English-speaking, audiences.

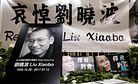

Yet despite the continuous effort to “to tell China’s story well,” such as establishing international news networks (e.g., China Global Television Network, China Radio International, Global Times) and training foreign journalists, China has seemingly lost at the global information war with “Western media imperialism” on issues concerning China. Pew polls have shown mostly negative images of China among North American, Western European, and neighboring Asia-Pacific countries. Given the belief in the greatness of their nation, its rich history, and astonishing accomplishments, the difficulties with telling good stories about China have been puzzling to most Chinese. China indeed has many good stories, but the CCP is not good at telling them.

China has been over-reliant on state media outlets to explain its policy and improve its global image, and these outlets have mostly been brushed off as Party mouthpiece lacking credibility. Aware of this, Chinese media such as CGTN have tried claiming “editorial independence from any state direction or control,” yet these networks’ uniformly positive coverage of Chinese government practices and belligerent counters toward a “biased and hostile West” in line with the CCP’s narrative suggest otherwise. The media’s sterile and dully massaged images reflect confusion within the Chinese bureaucracy on how to communicate its messages effectively within a realm with multiple actors and diversified opinions.

Chinese media, leaving the comfort of operating in the opposition-free domestic realm, faced difficulties in establishing a form of credibility that doesn’t come from a central authority. The issue goes beyond the ineffective propagation of the Party’s vague “theories, directions, principles, and policies,” which even ordinary Chinese find hard to grasp conceptually. Chinese media outlets have often attempted to counter criticisms by presenting narratives that lack a factual basis, such as accusing “foreign forces” of being behind the Hong Kong protests without presenting evidence. Given the CCP’s history of using the media as revolutionary and governance tools, the globalizing Chinese media outlets have faced difficulties in abandoning the paternalistic mindset that dictates the top-down, one-way characteristic of its messages. As China expert David Shambaugh puts it, China’s state media “basically have taken their domestic propaganda template and tried to go global with it.”

Even if the frontline media professionals are aware of these issues, their suggestions to improve communication are usually overruled by politically-motivated bureaucrats who think otherwise. Given the leadership has commanded that “all news media run by the Party must work to speak for the Party’s will and its propositions, and protect the Party’s authority and unity,” self-censorship that adheres to the principle of ideological cohesion and Party narratives runs the least risk of wrongly “figuring the intentions of the superior” (揣摩上意).

While the global presence of China’s media outlets has expanded, their credibility has plummeted within liberal democracies. The leadership may be aware of this problem and has borrowed insights from its rapidly evolving domestic social media landscape to improve its credibility. The leadership has commanded the “development of media integration to strengthen the penetration, guidance, influence, and credibility of the media.” Under this backdrop, the Chinese have adopted Trump-style “Twiplomacy” — the BBC has identified 55 Twitter accounts managed by Chinese diplomatic missions in 2019. Given the idea that

China’s diplomatic personnel “can’t afford to look weak or defiant,” as the BBC put it, the Chinese diplomats have tweeted with a markedly belligerent stance that is perceived as “politically correct” and thus risk-free.

Additionally, multiple Twitter and Facebook accounts have been identified as components of China’s misinformation campaign directed at interfering in the Hong Kong protests and Taiwan elections. While the concealed nature of these propaganda measures reflects the bureaucracy’s awareness that government presence undermines media credibility, the implications are severely detrimental to China’s image. Should reports of state-backed propagation of inaccurate information become more frequent, the paranoia of Chinese political interference will become pervasive; increasing distrust of China will propel the widespread tendency to brush off pro-China contents as propaganda, depriving China of channels to “tell China’s story well.” The Chinese publicity department has also attempted to co-opt influential soft power resources like internet celebrities into China’s propaganda machine. By doing so, the government risks thwarting the spontaneous genius of individual content producers that present a softer, apolitical side of China – such as Li Ziqi. Another effective channel to promote China’s image would then be clogged.

As the Chinese like to say, “it takes time.” However, faced with mounting external pressure and with the current administration’s emphasis on “confidence in the path, theory, system, and culture of socialism with Chinese characteristics,” government officials may be more incentivized to continue down the current path without rectifications.

This does not mean China’s increasing media presence and propaganda is ineffective in regions outside of North America, Western Europe, and neighboring Asia-Pacific countries. Pew poll have reported the increased favorability of China in parts of South America as well as South and Eastern Europe — but that’s a topic for another day.