On September 16, the Cabinet of the Solomon Islands voted to switch its diplomatic recognition from Taipei to Beijing, ending its 36-year-old official relationship with Taiwan. Kiribati switched three days later. This quick succession of diplomatic losses dropped Taipei’s formal diplomatic partners to 15.

While the switch by the Solomon Islands was a long time coming – China is its largest export market by a large margin, and investment, tourist, and cultural links with China have dwarfed those with Taiwan – it represents the reality of Beijing’s successes in campaigning against Taiwan’s status in the international system. Since Tsai Ing-wen took office in 2016, China has chiseled away six of Taiwan’s partners from Africa, Central America, and the South Pacific.

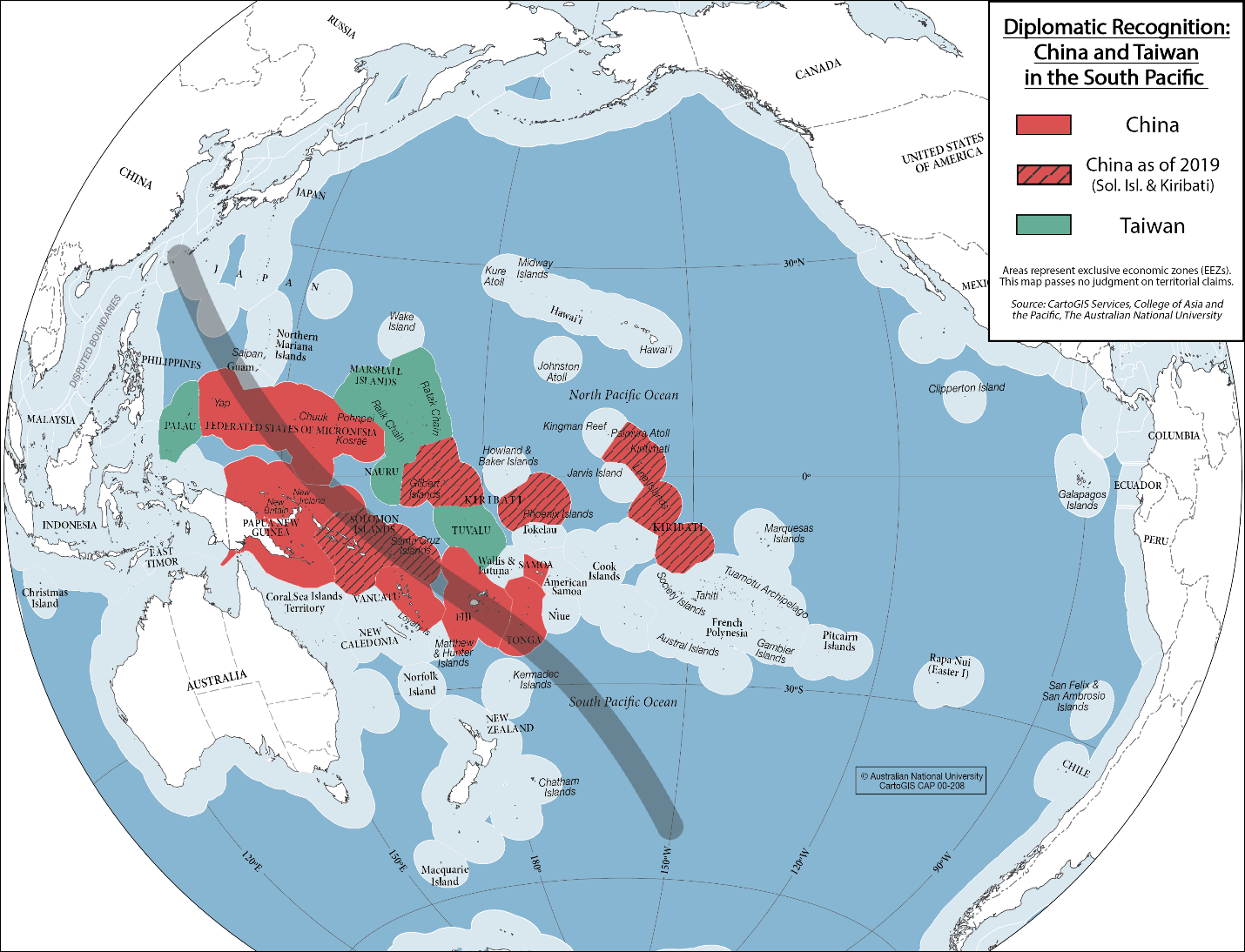

The switch by the Solomon Islands is highly significant for Taiwan, but other actors including the United States and its alliance partners in the Pacific are also deeply impacted. The Solomon Islands are strategically located and contain several deep-water ports, which means they could be used to directly challenge the activities of the United States and its partners in the region. With its diplomatic switch, a continuous strip of exclusive economic zones of China’s diplomatic partners runs more than 8,500 kilometers from Taiwan southeast to Tonga, jutting into the post-World War II spheres of influence of the United States, Australia, New Zealand, the United Kingdom, and France.

This map represents the changing state of China-Taiwan diplomatic recognition in the South Pacific, with island nations’ exclusive economic zones (EEZs) colored accordingly (with hatched areas representing recent diplomatic switches in 2019). Map modified from: CartoGIS Services, College of Asia and the Pacific, The Australian National University.

Coupled with concerns that China is planning to establish a naval base in Vanuatu and China’s elevation of its Pacific partners to “comprehensive strategic partner” level in 2018, the Solomon Islands’ change of recognition has amplified fears of a Chinese security presence in the region. Recent reports of a Chinese state-owned conglomerate attempting to lease an entire island in the Solomons illustrate the continued concern about Chinese militarization of Pacific island assets.

In September this year, days after the diplomatic switch, China’s Sam Enterprise Group (中国森田企业集团) made a deal with a provincial government to gain exclusive development rights to the island of Tulagi for 75 years. Local residents and international observers worried about the possible dual-use of the island given its history as a Japanese naval base and as a Pacific theater linchpin. While the deal was deemed illegal by the central government, the lack of transparency and the possibility of dual-use development keeps observers worried about the nature and content of future deals China may offer Honiara.

Compounding speculation about militarization of the region, the national security implications of large Chinese infrastructure projects have raised concern in the Solomon Islands and elsewhere. Australia, which sees the Pacific as its primary sphere of influence and this line of islands as its First Island Chain, has notably voiced unease about Huawei investments. In 2018, Canberra prevented a Chinese company from leading a large infrastructure project in the region by awarding an Australian firm nearly $95 million to build a 4,800-km undersea cable linking Sydney with Honiara and Port Moresby.

The switch in ties will also deeply affect the 670,000 Solomon Islanders themselves. The Solomon Islands is susceptible to dangerously large loans, which China’s banks and state-owned enterprises have been eager to provide under the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI). The country has the second lowest electrification rate (62.9 percent in 2017) and lowest Human Development Index (0.546 in 2019) of any small Pacific state – two factors that make the country good candidates for large infrastructure projects and susceptible to politicians making audacious promises to constituents.

The island nation’s limited credit and economic capacity makes it vulnerable to becoming overloaded with riskier Chinese debt: its most recent Moody’s rating is B3 (2015), lower than Sri Lanka’s B1 rating in 2016, the year before the Hambantota port was leased to China for 99 years. The lesson from Hambantota for the Solomon Islands is that even countries with better debt resiliency have fallen victim to ballooning debt. For the Solomon Islands, the coexistence of a huge demand for investment in its less-developed economy and China’s newfound diplomatic avenues to invest should paint a cautionary tale, particularly given China’s less-conditional concessional loans.

Beyond economic vulnerability, corruption associated with both the Solomon Islands and past BRI projects will also be a serious issue to tackle following the switch. The Solomon Islands has a track record of corruption, highlighted by allegations of bribes of more than $200,000 offered to MPs to support the diplomatic switch. Concerns over graft from Taiwan-funded development initiatives, like the Rural Constituency Development Fund, already exist, and the government’s failure to tighten lax rules surrounding donors should worry observers. On the Chinese side, renegotiations of large Chinese loans, such as those in Malaysia, have shown that past loans may have been inflated and may unfortunately include terms that line the pockets of corrupt officials rather than contribute to the Solomon Islands’ prosperity.

The Solomon Islands’ geography and economy make it a strategic linchpin in the South Pacific. Regardless of its strategic weight, the Solomon Islands deserves a sustainable path toward development, and whether that path can be forged with increased Chinese investment brought about by the diplomatic switch remains uncertain. For interested countries and for the people of the Solomon Islands, increased international scrutiny of investment deals between the Solomon Islands and China is essential. Transparency will be vital to understanding the broader strategy in the most expansive part of the Indo-Pacific within a context of great-power competition.

Jason Li is a Research Assistant in the East Asia Program at The Stimson Center, Washington D.C.