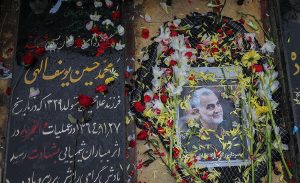

The consequences of the U.S. killing of Iran’s top general, Qassem Soleimani, have begun.

Insecurity looms in the entire Middle Eastern region as fears of a widespread conflict grow. The Iraqi government is taking measures to remove U.S. troops from the country while the anti-ISIS international coalition has halted its operations in the region. Last night, Iran. in a counter-strike, targeted U.S. military bases in Iraq, which according to Iranian state television, killed at least 80 Americans. If Iranian claims are even moderately true, the conflict is set to intensify in the coming days and weeks.

In any case, the prevailing tensions between Iran and the United States are set to affect Pakistan’s interests and, for Islamabad, the conflict couldn’t have surfaced at a worse time.

The situation poses a blow to Pakistan’s economic, diplomatic, and security interests in the region. Pakistan’s fears can be gauged from the statements that the country’s military and political leadership have given. Islamabad “will not be a party to this regional conflict” and “Pakistan’s soil will not be used against any other state,” said the country’s Foreign Minister. In a separate statement, the spokesperson of Pakistan’s military reiterated that “Pakistan will not be a party to anyone or anything but will be a partner of peace and peace alone.”

In both statements, the focus on staying “neutral” in the conflict is where Pakistan aims to keep its role in the ensuing conflict. Pakistan’s fears are understandable: in the past, Washington has coerced Pakistan to serve its interests aimed at isolating Iran in the region. While Pakistan has conformed due to fears of becoming a target of U.S. hostility, the relentless condition of hostility between Tehran and Washington has undermined Pakistan’s economic interests to a great extent. Irrespective of Pakistan’s constraints, the former considers Iran a potential partner in the field of energy, transport, and trade. Iran has 17 percent of the proven gas reserves in the world and for Pakistan to find a sustainable solution to its growing energy needs, open trade links with Iran are essential.

Moreover, the states in the Gulf region, particularly Saudi Arabia, have pressed Pakistan to isolate the latter’s vision of opening energy corridors and regional trade routes with Iran. For the past three decades, sectarian tensions in Pakistan due to the Saudi-Iran rivalry remained a highlight of Pakistan’s domestic security challenge. Economically, Pakistan’s dependence has grown on the Gulf states – a bitter reality that Islamabad has to live with as the cooperation is hardly mutually beneficial. For decades, to sort out recurring fiscal deficits, Pakistan has looked to the Gulf states for help. However, the help has always come with strings attached and, most of the time, these strings are focused on isolating Iran’s footprint in the region and constraining Pakistan’s ability to run an independent foreign policy.

In 2015, after the Pakistani Parliament’s decision to stay neutral in the Yemen conflict, the UAE warned Islamabad of that it would pay a “heavy price” for taking an “ambiguous stand” on the conflict and termed it as “siding with Iran.” Most recently, Saudi Arabia pressured Pakistan into withdrawing from the Kuala Lumpur Summit, an initiative that Riyadh considers a threat to its dominance in the Islamic World. If this is any indication of Pakistan’s constraints, the unfolding crisis in the Middle East has the potential to shake Pakistan’s foreign policy priorities, which will leave an impact on the country’s economy and domestic security.

For some years, Pakistan has pushed to balance its relationship between Riyadh and Tehran. The current prime minister of Pakistan, Imran Khan, talked about mediating between Iran and Saudi Arabia before even winning the polls. The strategic push in this regard doesn’t overtly focus on pushing Pakistan out of the Saudi block, but to showcase that the former’s relationship with Tehran doesn’t stand to undermine the Riyadh’s interests. I have argued previously for The Diplomat that such an effort is unlikely to be taken seriously unless there exists a domestic intent on the part of Tehran and Riyadh. However, the policy does offer Pakistan some space not only in terms of balancing its relationship between the two countries, but also in terms of gaining support on subjects that are strategic for Islamabad, particularly the issue of Kashmir.

A recent essay published by the Atlantic Council argued that more than anything else it’s the issue of Kashmir that is driving Pakistan’s mediation efforts between Tehran and Riyadh. That policy, however, may have fallen flat due to the developing situation in the Middle East if it was not already after the September attacks on the Saudi oil facilities which Riyadh blames on Tehran.

To Pakistan’s frustrations, neither Saudi Arabia nor the United States has openly criticized India’s abrogation of Article 370A of the constitution, which made Jammu and Kashmir a union territory of India. Iran, however, has openly condemned India’s move in Kashmir and called for dialogue between Islamabad and New Delhi, hinting that the issue is not India’s internal matter. For the past few months, Kashmir has headlined globally and became the focus of the international community’s worries as two nuclear powers spat over it raised alarm bells everywhere. Irrespective of Washington or Riyadh’s disinterest in the Kashmir issue, the situation in Jammu and Kashmir remained a key talking point for months. While Pakistan may not have been able to extract concrete support from Washington or Riyadh, President Trump’s statements and tweets about his potential mediatory role between India and Pakistan have hyped Islamabad’s plan of attracting international support to the issue.

It’s unlikely that going forward, Kashmir will remain an issue that is deemed a threat to international security due to the unfolding situation in the Middle East. This is going to hurt Pakistan’s Kashmir policy as the Iran-U.S. situation and other complications tied with it can take the focus away from Islamabad’s interests.

Moreover, the situation at the Iran-Pakistan border may become a challenge for Islamabad as militant groups based in the region may try to take advantage of the ensuing chaos. While both countries have been able to manage cross-border terrorism, Pakistan may have to deploy additional resources and focus to the Iranian border which may strain Islamabad’s emphasis on the Afghanistan border and along the Line of Control (LoC) with India.

Domestically, there are fears of a sectarian conflict resurfacing again. Already, several Shia groups in Pakistan have condemned the U.S. killing of the Iranian general and warned Islamabad of consequences if the country sided with Washington. Reportedly, the slain head of Iran’s Quds Force, Qasem Soleimani, was running operations focused on the Arab Middle East, and the new leader of the group, Esmail Qaani, has managed operations focused on Pakistan and Afghanistan. According to a report, Qaani’s

oversight of Iran’s Eastern front had seen him deal with Pakistan on three sensitive issues. The Quds Force role in liaising with the Taliban, securing Iran’s long eastern border and in recruiting Pakistani Shia volunteers for the Syrian war are all touchy subjects between Islamabad and Tehran.

This doesn’t bode well for Pakistan’s domestic security as it’s expected that the new head of the Quds force may use his contacts and channels to revive Shia militancy in the region to undermine U.S. and Saudi interests. Over the last few years, Pakistan has made huge gains when it comes to containing terrorism and sectarian militancy domestically. Islamabad wouldn’t want these gains to become a battleground of another regional war. However, there are clear risks of a new phase of sectarian battle breaking out in the months and years to come if the situation in the Middle East didn’t improve significantly.

In the immediate run, for Pakistan, the worst-case scenario rests with the dangers of an all-out war between the United States and Iran. In such a case, Washington and its ally Saudi Arabia may demand Islamabad’s support, including permission to use the country’s air space. This is not a scenario which Pakistan’s military and political leadership would like to imagine let alone become a part of. However, if things did get into this phase, Pakistan will be forced to choose a side that will have implications for the country in the months and years to come.

Already, the U.S. Secretary of State and Secretary of Defense have spoken to Pakistan’s military leadership and termed Islamabad’s role as an “ally” and “partner” in the context of the unfolding crisis with Iran. Historically, such titles have been poured on Pakistan when the United States needed Islamabad either to fight against the Soviet Union or break Pakistan’s relationship with Taliban in Afghanistan. Reportedly, Pakistan’s military leadership has told the United States that de-escalation should be the way forward as the growing escalation will undermine regional peace including the Afghan peace process. Now, more than ever before, there is no clarity on how the peace talks with the Taliban will proceed and what kind of leverage will the United States have after the growing opposition from all quarters in the Middle East. And even within Afghanistan.