Last weekend, the Indian government announced its budget amid an economic slowdown and questions about its economic policies. In this environment, the annual Economic Survey, which is authored by the government’s chief economic adviser, highlighted a glimmer of hope, noting that the number of firms created since 2014 has seen a substantial rise, and claiming that as a sign of growing entrepreneurship.

That narrative, however, is built by severely contorting data. An analysis of the overall number of registered companies not only highlights a more sobering state of the economy, but also calls into question the validity of the data on companies, which is used to measure GDP growth.

Twisting the Facts to Fit the Narrative

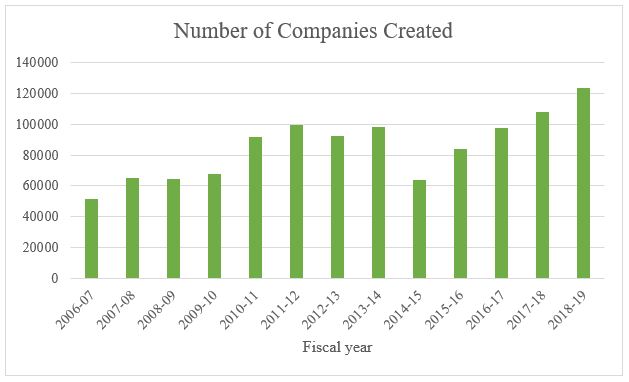

In the economic survey, the government claims that firm creation increased from a compounded annual growth rate of 3.8 percent from 2006-2014 to 12.2 percent from 2014-2018. But the data published by India’s Ministry of Corporate Affairs (MCA) paints a different picture. According to MCA data, the number of companies created rises steadily from 51,700 in the fiscal year from March 2006 to April 2007 (FY07) to 99,600 in FY12 and largely plateaus for two years, only to fall in FY15, the majority of which was under the Modi government (see Figure 1 below).

By citing World Bank data, which uses annual instead of fiscal year data, to come up with its analysis, the government tries to pin the decline in FY15 on the previous administration, thereby reducing the growth seen under the previous government, and lowering the baseline against which it measures itself.

Comparing the aggregate number of companies created during a time period is a far more important number than the growth rate between two snapshots of time. MCA data shows that a total of 476,800 companies were created between FY15 and F19, the first term of the Modi government. That was only 6 percent higher than the 449,100 companies created between FY10 and FY14.

In the last year of the previous government (FY14), 98,000 companies were registered. The number of firms registered during the present government did not surpass that number until FY18, when 108,000 firms were registered.

Figure 1

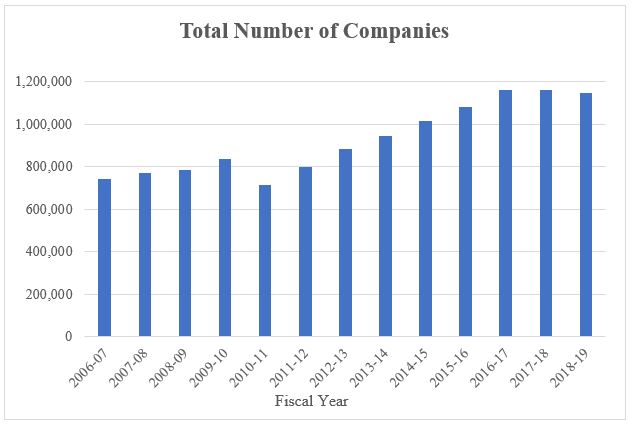

The government not only misrepresents the data, but it also focuses on an incomplete picture. While the number of firms being created could be a sign of entrepreneurship, such a trend would only be significant if these companies were to sustain themselves, leading to an overall increase in the number of firms.

In the first three years of the Modi government the total number of firms increased steadily from around 950,000 in FY14 to 1.16 million in FY17 (see Figure 2 below). In the last two years, however, the number of overall firms plateaued and dipped slightly to 1.15 million.

Figure 2

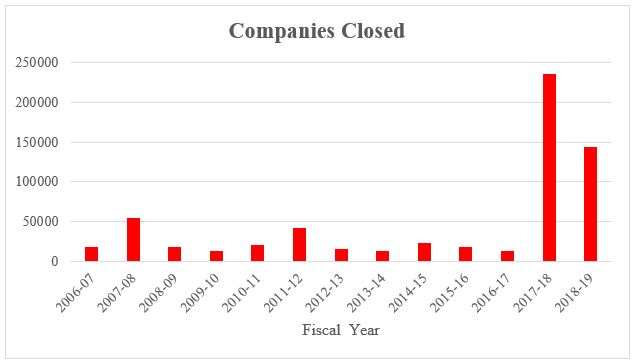

The unusual plateau appears to have happened due to a large spike in the number of companies removed from the government’s database. 236,300 were removed in FY18, which was equivalent to almost 20 percent of the overall registered companies that year (since 108,000 companies were registered in FY18 and over 236,000 were closed the total number of companies should have decreased by a larger number. It’s unclear what is causing the discrepancy in the data). An additional 143,200 were removed in FY19.

The sharp rise in the number of companies closed (see Figure 3) has largely been driven by the government’s efforts to shut down companies that have not filed the required paperwork, as such entities are suspected of being shell companies. The government has touted such efforts as part of its efforts against black money.

Figure 3

Is the Data Representative of Economic Trends?

While the government is celebrating a substantial rise in the number of companies, there are multiple questions about the quality of data about companies collected by the MCA. The MCA and the government should receive credit for removing a large number of unregistered companies over the last two years, but their lack of transparency surrounding the database and what steps they are taking to restrict new spurious registrations raises concerns.

First, the trend in new companies registered does not correspond to economic activity. There were over 92,000 companies registered in FY13, when India experienced economic turbulence, but only 64,000 and 84,000 companies registered in FY15 and F16, when economic growth was seen as being much higher.

A study conducted by India’s National Sample Survey Office in 2017 found that 16.4 percent of the companies registered in an MCA database could not be traced or were closed, and a further 21.4 percent were found to be out of “coverage,” suggesting that they were not operating as they had specified on their application. Since that database feeds into India’s GDP growth calculations, the report raised concerns about the larger impact of such shell entities.

Since India implemented a nationwide Goods and Services Tax (GST), beginning in July 2017, tax officials are highlighting that gaps in the refund system have led to a rise in shell firms springing up only to claim fraudulent refunds. One case included a network of 500 firms that claimed such refunds.

Managing Perceptions, Ignoring Reality

The Economic Survey is intended to highlight trends and generate conversation about policy options among those who follow the economy closely. Conducting data acrobatics in a document that most voters are unlikely to ever read highlights the desperation of the government to spin a positive narrative. Intentionally contorting the data, combined with the Economic Survey’s citation of Wikipedia in two instances, raises questions over whether the government is being rigorous and honest in its assessments.

These steps are all the more concerning because there is a great need for rigorous analysis of Indian companies’ data. The government has removed over 370,000 companies over the last two years, and the economic conversation could benefit from more information about the nature of those companies, when most of them were created, and if their inclusion or removal had a large impact on GDP calculations.

While removing suspect companies is important, creating better processes so that such companies cannot re-register is also critical. So far, is unclear if the newly registered companies are any more likely to be authentic.

Researchers have called on the government to provide access to MCA’s companies database so that they can better understand the quality of the data. Having a more transparent analysis in the Economic Survey would have been a first step to generating a dialogue around this important issue.

In the irony that often defines India, the government is simultaneously touting an increase in the number of companies registered and the number of companies struck off for being shell entities. The government would be better served by leaving the data contortions for its social media campaigns and allow the Economic Survey to focus on analyzing important issues surrounding India’s serious economic challenges.

Shezad Lakhani is a former economic analyst with the U.S. government whose career focused on South Asia. He is located in Santa Clara, California. Follow him on Twitter @Shezadl1. The views expressed in this article are the author’s alone and do not reflect those of his employer.