In Japanese politics, bribery and corruption occur from time to time. In a recent case, Tsukasa Akimoto, an up-from-the ranks Diet member of the Liberal Democratic Party (LDP) and former state minister in the Cabinet Office in charge of integrated resorts businesses, including the introduction of casinos to Japan, was arrested on December 25, 2019 for suspected receipt of a 3.7 million yen (about $33,610) bribe from a Chinese gambling company, 500.com.

The casino-related bribery scandal did not stop with Akimoto’s arrest, either. Mikio Shimoji, a Diet member of Nippon Ishin (Japan Innovation Party), also admitted to receiving a 1 million yen bribe from an adviser of the same company. Four other LDP lawmakers were suspected of receiving money from the company, including former Defense Minister Takeshi Iwaya.

Diet members are representatives of the people in Japan, and are able to exert political influence over lawmaking processes and certain businesses and industries. Needless to say, they earn decent wages.

Why, then, do some Japanese Diet members end up embroiled in bribery and corruption?

In Japan, the National Diet is the “highest organ of the state power” and the “sole law-making organ of the state.” It consists of two houses, namely the House of Representatives (the lower house) and the House of Councillors (the upper house). Both houses are composed of Diet members who serve as “elected members, representative of all the people.”

There are three main privileges for Japanese Diet members. First, they can receive “appropriate annual payment” from the national treasury. Second, Diet members are “exempt from apprehension” when a Diet session is open. Third, they are not “held liable outside the House for speeches, debates, or votes cast inside the House.” There are, of course, additional perks that come with a seat in the Japanese Diet. For example, they can choose to receive 1) a Japan Rail (JR) free pass, including to the green carriage of a bullet train (Shinkansen), 2) a JR pass plus airfare coupon for three round-trips a month, or 3) airfare coupon for four round-trips a month.

As noted above, Japanese legislators receive “appropriate annual payment.” In 2019, it was announced that the average annual income of Japanese Diet members in 2018 was 26.57 million yen, inflated by the income of Jiro Hatoyama, the top earner of the year, who took in 1.74 billion yen. The income of Prime Minister Shinzo Abe, as the 27th earner, was 40.28 million yen.

But precisely how much is the annual income of a Diet member?

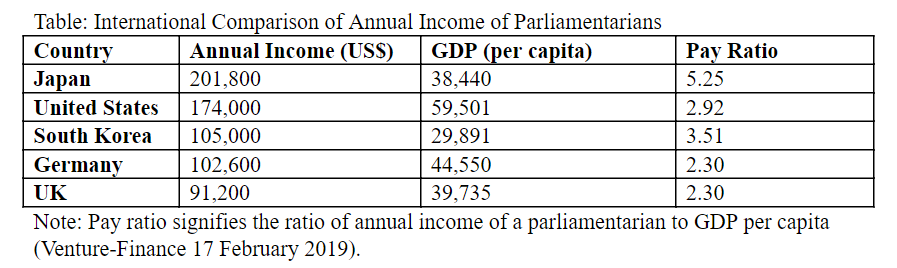

The basic monthly salary of a Diet member is 1,294,000 yen, (15,528,000 yen annually). In addition, the annual bonus of a Diet member is 6,350,000 yen. So the total annual income of a Japanese legislator amounts to 21,878,000 yen. The annual income of a legislator in Japan (about $201,800) is higher than that of a comparable legislator in the United States ($174,000), South Korea ($105,000), Germany ($102,600), and the United Kingdom ($91,200). As shown in the table below, it is obvious that Japanese lawmakers earn higher wages compared with parliamentarians or legislators of other countries, as well as average Japanese workers.

On top of this, each Diet member can receive 1 million yen, in a tax-free allowance, as bunsho tsushin kotsu taizaihi (budget for document, communication, transportation, and accommodation) every month, totaling 12 million yen per year. Diet members can use this budget for their official activities, but they are not required to submit receipts for its use. Of course, Diet members can save the rest of the budget, if they prefer, so it can be regarded as a general source of tax-free income. Accordingly, the exact total annual income for a Japanese Diet member amounts to as much as 33,878,000 yen.

Clearly, the annual income of Japanese parliamentarians is high. Why, then, do bribery and corruption occur in Japanese politics? This is because there is no guarantee that existing Diet members will win in the next election, and it costs considerable amounts of money to run for national election (the deposit for candidacy is 3 to 6 million yen). In this way, there is always the possibility that some Diet members may end up being unemployed after the election. Therefore, Diet members tend to collect and save as much money as possible in their limited term in office.

The term of office for Diet members in the lower house is four years, but their term could be ended earlier if the lower house is dissolved by the prime minister. So in reality, Japanese legislators of the lower house tend to work for less than three years in each term, on average. The term of office for Diet members in the upper house is six years, and election for half the members takes place every three years. Some legislators have complained that their annual incomes are not necessarily sufficient for proper political activities and electoral campaigns, given the limited term, especially in the lower house.

For this reason, political parties throw fundraising events a couple times per year. Donors, as supporters of Diet members, purchase a fundraising ticket for 20,000 yen or so. This is how some Diet members are able to raise more than 10 million yen a day. Throwing political fundraising parties is lawful on the basis of Article 8-2 of the Political Funds Control Act. Likewise, donations to political groups are lawful, but Article 22-5 of the Act bans political contributions from foreign persons and foreign entities.

In order to become Diet members in Japan, candidates need to have qualifications fixed by law (Japanese citizenship, over 25 years old for the lower house, over 30 years old for the upper house), and there is no discrimination based on “race, creed, sex, social status, family origin, education, property or income.” Having said that, unlike the case of second-generation Diet members or hereditary legislators, most young candidates or novice Diet members from humble backgrounds will need to save money on their own and prepare for the possibility of being unemployed.

Of course, bribery should not be tolerated or justified under any circumstances, and it is ultimately a question of the personal morality and integrity of each politician. But the unstable status and different economic backgrounds of Diet members might be regarded as one of the remote causes of bribery and corruption in Japanese politics.

Daisuke Akimoto is Official Secretary in the House of Representatives, Japan and former Assistant Professor at the Soka University Peace Research Institute. He holds a Ph.D. in Asian Studies and International Relations from the University of Western Sydney and an MA in Peace and Conflict Studies from the University of Sydney. His recent publications include “The Abe Doctrine: Japan’s Proactive Pacifism and Security Strategy” (Palgrave Macmillan, 2018). His views are his own and do not represent the House of Representatives or the Japanese government.