The coronavirus outbreak death toll surpassed 1,100 this week, with confirmed infections ballooning to more than 44,000. Debate continues to rage over the severity of the virus’ economic consequences. But the global economy and supply chains are not the only international processes disrupted; Chinese diplomatic efforts are also likely to suffer as the Chinese state’s bureaucratic apparatus has been reoriented to address the impact of the public health emergency.

Earlier this month, Xi Jinping’s “disappearance” raised questions about confidence in the Chinese system in the face of crisis. Chinese leadership has been criticized for its initial response to the coronavirus outbreak and for its crackdown on the dissemination of information. (Journalism controls have since somewhat eased, with Chinese media outlets covering a wide array of angles concerning the outbreak and probing tough questions.) Xi’s visible absence may have been an attempt to distance himself from blame. “Someone has to take responsibility for the ongoing spread of the coronavirus, and he may not want to be that person,” Bruce Dickson, China expert and chair of the political science department at George Washington University, told the Washington Post. Instead, Premier Li Keqiang and Vice Premier Sun Chunlan (the latter of whom has a portfolio that includes public health policy) were the officials tasked with heading to the frontlines in Wuhan and inspecting China’s new emergency hospital units. The Chinese president re-emerged this week in Beijing, donning a face mask for his first public appearance since greeting Cambodian leader Hun Sen during a state visit in early February.

Jin Kai, an associate professor at the Institute of International Studies at the Guangdong Academy of Social Science and current visiting fellow at the Sigur Center for Asian Studies at George Washington University, wrote in The Diplomat that the fight against the outbreak “must be implemented with a ‘whole-of-government’ and ‘whole-of-society’ approach,” which includes not only government efficiency and transparency, but also the participation of the general public. Redirecting the priorities of Beijing’s central leadership, including the creation of a new leading group dedicated to the fight against the coronavirus, is one way in which the Chinese system has reoriented to the domestic front. Even the Ministry of Commerce has been active, issuing a circular for local authorities to expand imports in order to increase the availability of medical supplies.

The content of Chinese Foreign Ministry press conferences also signals an inward shift to address the outbreak. In addition to signaling domestically that the Chinese Communist Party is resolutely committed to battling the virus, Beijing is actively working to regain control of the international narrative, or at the very least shape it. For example, in response to questions about the World Health Organization’s declaration of a public health emergency, China’s Foreign Ministry Spokesperson Hua Chunying said “the Chinese government has taken the most comprehensive and rigorous prevention and control measures with a strong sense of responsibility for people’s health,” adding that Beijing had acted with openness and transparency. The press briefings have also included thanks for countries providing support of both the rhetorical and material kind, invoking the saying “a friend in need is a friend indeed.” Not all messaging has been positive, however, with officials chiding decisions by certain countries to impose travel restrictions, including Italy and the United States.

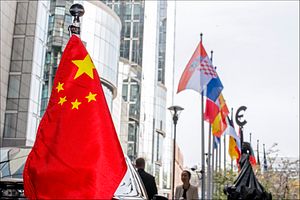

The outbreak has also stymied China’s diplomatic engagement. Xi may postpone his state visit to Japan slated for April, a development that could impact the steadily warming ties between Beijing and Japan over the past several years. The fates of the China-EU summit, scheduled for late March, and the subsequent April “17+1” meeting between China and 17 Central and Eastern European nations, remain unclear. Beijing and Brussels were expected to conclude an investment deal in 2020, but the negotiation schedule is likely to face setbacks. Separately, Chinese Foreign Minister Wang Yi heads to Germany this week to attend the Munich Security Conference, where he will be responsible for selling China’s efforts to combat the virus on a high-profile international stage.

Other more routine diplomatic efforts (including phone calls between Wang and his counterparts in neighboring countries and beyond) have concentrated on demonstrating widespread international support for China during the health crisis. Although the virus is unlikely to upend China’s ongoing outward expansion, Beijing’s temporary, narrow focus on the homefront may still slow or stall foreign policy progress in early 2020.