As of this week, most should finally agree that coronavirus is no longer strictly an Asian problem. At the time of writing this piece, Italy has 3,858 confirmed cases while Iran has 4,747. For both countries, the issue is no longer about outbreak prevention but about virus containment. The only country other than China with more cases is South Korea, at 6,593. As the second nation to have experienced an outbreak, the Korean story offers some important insights into the many challenges associated with containment, issues that should be studied carefully by any country hoping to overcome an outbreak.

The Good

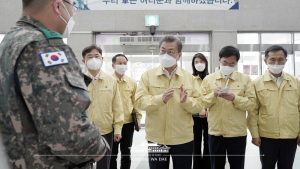

As a cell biology Ph.D. from Yale living in Busan, South Korea, I have spent the last month working with local authorities, helping promote effective practices in the community. I have interacted with religious groups, workers, and community leaders, answering their many science questions. These interactions have placed me in a unique position, interfacing between authorities and the public, allowing me to experience firsthand the many challenges on either side.

In simple terms, containing an outbreak is about identifying and quarantining infected individuals as quickly as possible, preventing them from perpetuating viral transmission. In this process, the first and most important component is having a standard operating procedure (SOP). As the Iranian outbreak has shown, there are many countries without functional SOPs, making an organized response much more difficult. Even the United States and Japan are exhibiting varying levels of confusion, making me worry they too may lack actionable containment plans.

So far, South Korea and Taiwan are among the few countries to have demonstrated robust and consistent SOPs. This is not surprising given that each has invested heavily in infectious disease control following prior experiences with SARS and MERS. South Korea’s SOP essentially calls for five steps: an aggressive and transparent information campaign, high volume testing, quarantine of infected individuals, treatment of those in need, and disinfection of contaminated environments. These may seem like obvious measures, but proper execution is ultimately what decides their effectiveness.

Transparent information is always the essential first step in any containment effort. It is a simple economic fact that not everyone in a country can be tested. To maximize the odds that testing is focused on the people mostly likely to be infected, an aggressive information campaign is needed. In South Korea, this campaign communicates two critical components: risk factors and useful measures.

Risk factors refer to information about the immediate environment. Who around me has been infected? Did I unknowingly visit a convenience store with infected individuals? These are things people must know in order to make informed decisions about whether to get tested.

In South Korea, the answers to these questions are provided by the government daily through press briefings, websites, and automated text messages, which tirelessly communicate the recent locations traversed by newly diagnosed patients. Lists of restaurants, shops, and churches are accompanied by the approximate times of visitation so people can quickly decide whether they might have been at risk. Text messages arrive through a contact that is hard-coded into every phone so there is no question about its authenticity, alleviating concerns about pranks and false reports.

Useful measures include detailed explanations of the SOP and general advice about viral transmission. This advice appears daily through television, newspaper, and internet ads, reminding people to avoid crowded places and use appropriate preventative hygiene. All inputs together supply a heightened sense of clarity about how people can help protect each other and extinguish the outbreak. This information also functions as a heavy counterweight to rumors, myths, and misinformation, reducing the chances that people will be led astray into unhelpful practices.

Good information isn’t much use, of course, unless it is combined with effective virus testing. Here too, the government has been very decisive, making tests available nationwide by sending teams into rural areas and even setting up drive-through test centers in large cities like Daegu. Test volume and speed are essential for containing an outbreak. To this effect, South Korea currently has a daily capacity of over 10,000 tests, the most of any country. The results are quick too, reported by text message within 24 hours.

Every expert I have spoken to, domestic and abroad, agrees that South Korea’s information and testing are nothing short of enviable. The quality of these systems, however, doesn’t mean much unless the public is willing to use them. It is here that the murkier issue of voluntary compliance rears its head, bringing along essential considerations of culture and religion.

The Bad

The truth of the matter is that testing, quarantine, and treatment depend on voluntary public cooperation. If people don’t want to get tested, no amount of text messages will change their minds. A few media outlets have already noted that quarantines are never perfect. This is true, but at the same time, a higher rate of compliance will inevitably bring about a faster end to outbreaks, meaning cooperation saves lives. It is in this space between public commitment and doubt that I have found myself these last few weeks, trying to help people understand and comply with the SOP.

Although the central government may be able communicate with the public en masse, it lacks the ability to address specific questions. These include things like: are swimming pools safe? If an infected person sits in my chair, how likely am I to get sick? The sheer number and variety of these questions leaves an important void for local authorities to fill. In our interactions with the public, my colleagues and I have found that providing answers to these questions is an essential service, one that reduces panic, improves confidence in the SOP, and makes people feel like they have some fundamental control over their daily lives.

So how does culture play into this? Koreans, quite fortunately, tend to be very socially conscious, willing to go out of their way to reduce risks for others. From the perspective of virus containment, this is an incredible gift. In fact, most Koreans will readily admit they wear masks, not only to protect themselves, but also to help protect others. Get caught in the streets these days without one and you will most certainly be greeted with reproach. It is the potential absence of this cooperative culture that will likely be the first hurdle for many other countries when implementing their own containment efforts.

Despite its advantageous culture, South Korea has nevertheless experienced notable exceptions to public compliance. By the numbers, cases involving the elderly have been most prevalent. Through the last month, we have received sporadic reports of seniors across South Korea refusing testing or quarantine. The most publicized example is a 61-year-old woman in Daegu who refused testing on two occasions despite having significant contact with an infected patient. This woman, referred to as “patient 31,” ended up infecting another 37 people. Last week, the government passed a law making violations of quarantine by infected patients an imprisonable offense, giving doctors greater authority to protect the public. Other countries would do well to consider similar implements empowering their medical and emergency staff.

In Busan, we have also found seniors to be most likely to hold misconceptions and misgivings about the SOP. Part of this seems due to political leanings (discussed later) while another part is attributable to low science literacy. South Korea, as a nation, does have one of the highest rates of science literacy in the world but this characteristic rarely extends to those in their 50s and 60s. In several cases, my colleagues and I were forced to enlist the help of children or grandchildren to coax cooperation, relying on another aspect of Korean culture: strong familial ties.

A second, perhaps more important, group to consider are individuals of faith. Religious beliefs can have profound effects on cooperation if those beliefs come into conflict with science or the SOP. Similar conflicts are known to have prolonged the 2013-2016 Ebola epidemic in Africa. In South Korea, members and direct acquaintances of the church group Shincheonji account for a staggering two-thirds of all COVID-19 cases. The group’s unique worship style, which involves hundreds of people cramming together in confined spaces for hours, is indubitably responsible for high transmission between members.

Last week, the Ministry of Justice revealed 42 Shincheonji members had returned from Wuhan in January, making it extremely likely that the original virus carriers were among this group. Although not all details have been released to the public, it appears the Shincheonji organization also tried to hide the fact that its members were infected, contributing significantly to high outbreak numbers in Daegu and surrounding Gyeong-buk province, which together account for over 85 percent of all South Korean cases. Shincheonji’s head priest has since apologized by bowing before the media.

At the very least, these facts illustrate just how important it is for religious establishments to cooperate with containment efforts. Health authorities in other countries are strongly advised to reach out to their religious colleagues well in advance of an outbreak to share information and prevent a repeat of this sad story.

The Ugly

Over the last two weeks, some Korean media outlets have begun putting forth a steady stream of criticism about the Moon administration’s handling of the outbreak. These criticisms have exhibited a decidedly political slant with lawmakers from the opposition United Future Party taking the lead. The complaints focused initially on President Moon Jae-in’s decision in January not to place an entry ban on Chinese nationals, a decision that remains in place. Although this ban might have helped reduce the number of infections modestly, we now know, as explained above, that Shincheonji likely had a much greater impact. Despite the new information, criticisms have not abated. Instead, they have simply transferred to other topics, such as the shortage of protective masks.

As a scientist volunteering to maintain SOP compliance at the local level, I am extremely disappointed by this politicization of the outbreak. I can say with some authority that the negative coverage has started to make my job, and the jobs of my many colleagues, more difficult. Seniors, the demographic most likely to support the United Future Party and most likely to die from COVID-19, have recently started citing Moon’s “incompetence” as an excuse to dismiss or question SOP procedures, making everyone less safe and containment of the virus unnecessarily more challenging.

With an election slated for April, I harbor no hope that the United Future Party will read my words and repent. For foreign journalists, however, I hold higher expectations. Heaven forbid, if an outbreak starts in your country, there will be hundreds, if not thousands of people on the front lines engaging the public and struggling to establish an SOP. For their sakes and mine, please be careful divvying blame too early. It might actually make things worse.

Justin Fendos is a professor at Dongseo University in South Korea and a regular contributor for the Korea Herald.