South Korea has been praised for its response to the novel coronavirus disease (COVID-19), which combines widespread testing with innovative strategies such as public “phone booths” that separate a medical professional and patient and can provide results within seven minutes. Additionally, there have been efforts in triangulating available public and private data to track patients’ whereabouts and schedules. The United States, recognizing South Korea’s success, has even requested equipment, likely including test kits, from South Korea. The Moon Jae-in administration built upon South Korea’s previous experiences responding to outbreaks of both Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome (SARS) in 2003 and Middle East Respiratory Syndrome (MERS) in 2015.

Yet, despite mostly positive responses from foreign leaders and the outbreak’s potential to influence legislative elections next month, little international attention has been placed on how the South Korean public views the government’s response to coronavirus. While it might be assumed that domestic perceptions are similarly positive, our data suggests a more complex situation.

In order to capture public sentiment, we surveyed 1,111 South Koreans from March 2-12 via web survey, conducted by Macromill Embrain, using quota sampling by age, gender, and region based on census data. While this was after the initial wave of cases in South Korea, newly confirmed cases still ranged 600 on March 3 to 114 on March 12. We asked respondents to evaluate the statement “I am satisfied with the South Korean government’s response to the 2020 coronavirus outbreak” using a five-point scale, from “strongly disagree” (1) to “strongly agree” (5).

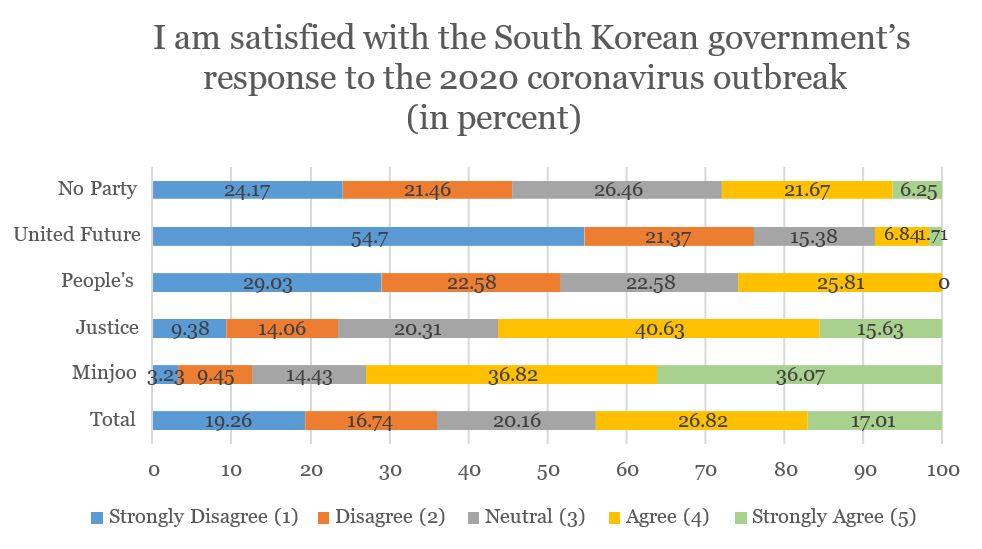

Overall, we see no consensus, with a plurality (43.83 percent) agreeing and over a third (36 percent) disagreeing with the statement. Among those with no party affiliation, we find noticeably less support (45.63 percent disagree versus 27.92 percent agree). However, among parties we see a very clear trend following ideological lines. Those supportive of President Moon’s Minjoo or Democratic Party largely agreed with the statement as did supporters of the progressive Justice Party, while supporters of the centrist People’s Party and the conservative United Future Party were more critical.

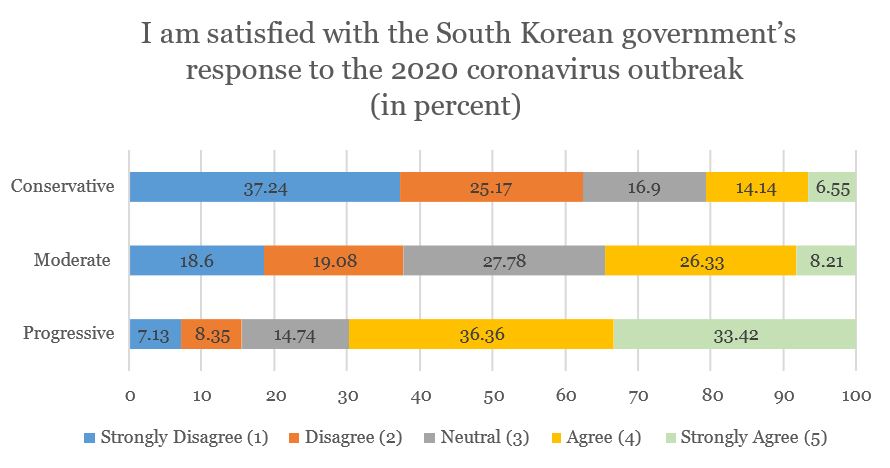

Concerned that these patterns may just be a statistical anomaly, we also broke down responses based on respondents’ self-identified position on an ideological spectrum. Here we see that self-identified progressives were over four times as likely to agree than disagree with the government’s response (69.78 and 15.48 percent respectively), whereas moderates were nearly evenly split. Conservatives also were three times more likely to disagree with the statement.

Next, we broke down evaluations by partisanship, and found stark differences. Support was highest among supporters of Moon’s own party, the Minjoo Party (3.93), and lower among the smaller, more progressive Justice Party (3.39). In contrast, evaluations were considerably lower among supporters of the centrist People’s Party (2.45) and the conservative United Future Party (1.79). A similar pattern emerges if respondents were separated by political ideology; progressives averaged a 3.81 on the scale compared to 2.86 and 2.28 for moderates and conservatives, respectively.

Regression analysis produced similar results. Progressives and supporters of the Minjoo Party and the Justice Party all positively corresponded with satisfaction with the government’s response, while conservatives and United Future Party supporters both negatively corresponded with such perceptions. Meanwhile gender, age, income, and education had no statistically significant influence. With the idea in mind that the location of the major outbreaks may influence perceptions, we also controlled for Daegu and Gyeongbuk, which comprised roughly 73 and 14 percent of cases as of March 20. However, neither inclusion in regression models reached statistical significance. Likewise, we controlled for the day of the survey to capture short-term trends, but this inclusion was also insignificant.

Despite broad international praise for South Korea’s response to the coronavirus, our data strongly suggests that there is no such consensus domestically, where party and ideological lenses largely shape perceptions. Perhaps this should come as no surprise, not only as strong partisanship and ideology are commonplace in democracies, but as such factors tend to be particularly salient leading up to an election.

Legislative elections are slated for April 15. To what extent opposition parties will focus on the Moon administration’s response to COVID-19 as a means to decrease the Minjoo Party’s plurality of seats is unclear. Opposition leaders argue that Moon’s government did not act fast enough, and instead hosted a gathering featuring the director and cast of Parasite when the country already had 100 coronavirus cases. Online petitions show a continued split, again largely on party and ideological lines, of those demanding Moon’s impeachment. and those in support of Moon. Moreover, our survey results suggest the difficulty in building a broad consensus on a crisis response when party and ideological divisions run deep, especially during an election season. Luckily for South Korea, previous experiences with comparable outbreaks have providing strong guidelines and allowed for quick responses rather than a devolution into partisan debates.

Timothy S. Rich is an associate professor of political science at Western Kentucky University and director of the International Public Opinion Lab (IPOL). His research focuses on public opinion and electoral politics, with a focus on East Asian democracies.

Isabel Eliassen is an Honors undergraduate researcher at Western Kentucky University majoring in International Affairs, Chinese, and Linguistics.

Andi Dahmer is a 2018 Harry S. Truman Scholar and recent graduate of Western Kentucky University.

Madelynn Einhorn is an honors undergraduate researcher at Western Kentucky University, majoring in Political Science and Economics.

Erin Woggon is a senior undergraduate researcher at Western Kentucky University and will be graduating in May with degrees in German and International Affairs.

Kaitlyn Bison is an honors undergraduate researcher and will be graduating in May with degrees in International Affairs and Economics.