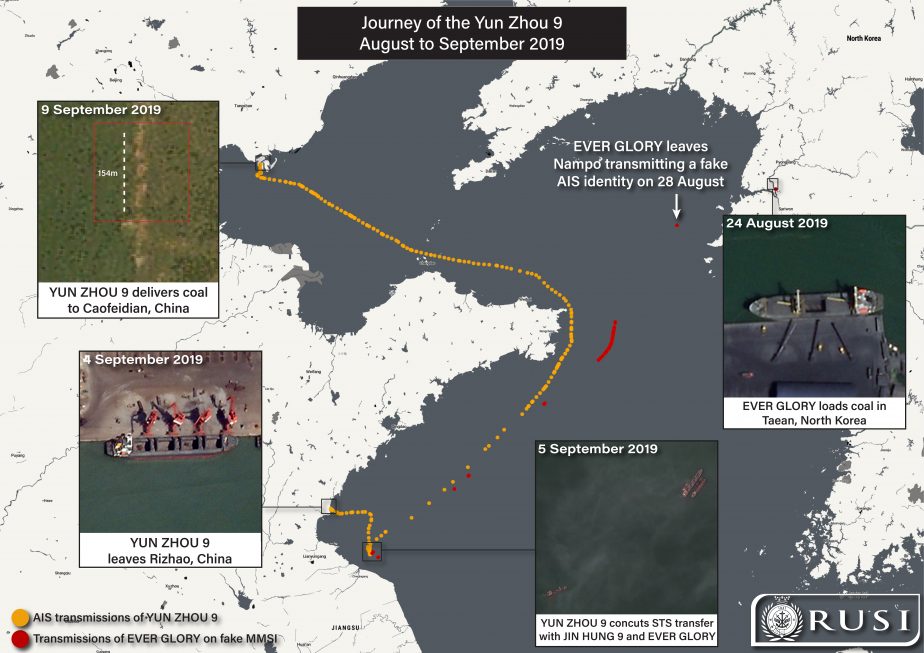

In August 2019, two aged North Korean-flagged cargo ships set sail from Taean, a port south of Pyongyang, and headed down the Taedong River out toward the Yellow Sea. It was a familiar journey for the Jin Hung 9 and Ever Glory and one that they had undertaken dozens of times in recent years as they ferried North Korean coal and other commodities to buyers abroad in China and farther afield.

The Ever Glory loading coal in Taean on August 24, 2019. Source: Planet Labs, RUSI Project Sandstone.

However, as increasingly stringent UN sanctions targeting North Korea’s nuclear and ballistic missile program took hold in 2016 and 2017, exporting these commodities became a lot more complicated for the regime in Pyongyang.

Largely excluded from the international financial system and global trade networks, North Korea and the crews onboard their merchant vessels were forced to adopt a panoply of measures to find buyers for their commodities and successfully export them abroad. From fake AIS transmissions to flag-hopping, front companies to fraudulent bills of lading, North Korea’s smugglers used every trick in the book to keep commodities flowing out and the revenue flowing in.

The Jin Hung 9 and Ever Glory were no exception. Owned and managed by Hong Kong-registered companies linked to North Korea’s illicit networks since 2015, the Ever Glory shuttled almost exclusively between North Korean ports and bulk handling facilities designed to process commodities during these years, all while flagged to countries other than North Korea: Sierra Leone, Tanzania, and the diminutive island state of Comoros.

But in August 2019, as the dilapidated 31-year old cargo ship exited the locks of Nampo’s West Sea Barrage along with the Jin Hung 9 and switched on her Automatic Identification System (AIS) transponder, the signals beamed into the atmosphere were not her own, but those of a nonexistent Nigerian vessel named the GE. The Jin Hung 9, which sailed along beside her, did not make any AIS transmissions for the duration of the subsequent journey to the waters off Lianyungang, a Chinese port city and the eastern terminus of Beijing’s ambitious Belt and Road Initiative.

A Date in the Deep Blue

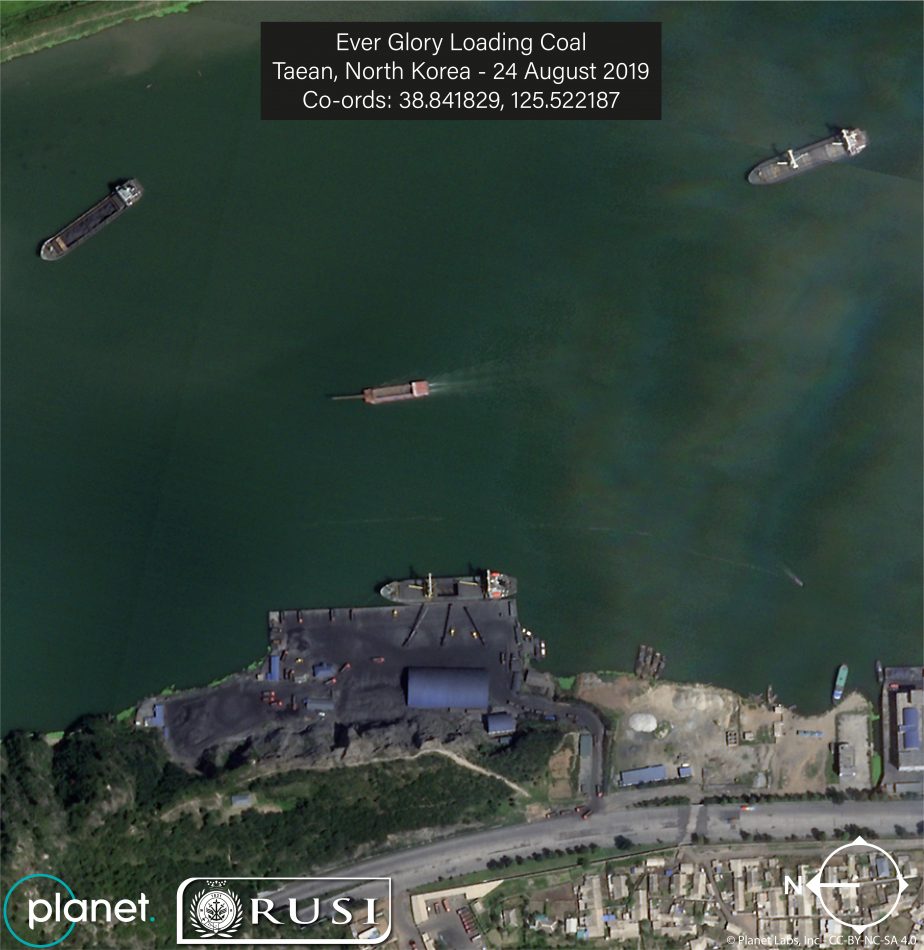

Meanwhile, 300 kilometers to the east of Nampo, a much larger Chinese flagged bulk carrier named the Yun Zhou 9 was anchored at a terminal in Heshang Island, Dalian, China. On September 1, the Yun Zhou 9 departed Dalian, and sailed south to Lanshan, a port in Shandong province designed to handle dry cargo. Here, high-resolution imagery collected by Planet Labs on September 4, 2019, shows the vessel called at Berth North 01, while AIS data collected by Windward suggests the vessel offloaded its cargo.

The Chinese-flagged Yun Zhou 9 offloading cargo in Lanshan, China on September 4, 2019. Source: Planet Labs, RUSI Project Sandstone.

Immediately after calling at Lanshan, the Yun Zhou 9 sailed for the waters off Lianyungang, where the Jin Hung 9 and the Ever Glory had anchored at the end of August. Here, roughly 40 kilometers away from port and out to sea, the Yun Zhou 9 had an appointment with the Jin Hung 9 and the Ever Glory, vessels that had loaded sanctioned commodities in North Korea only days before.

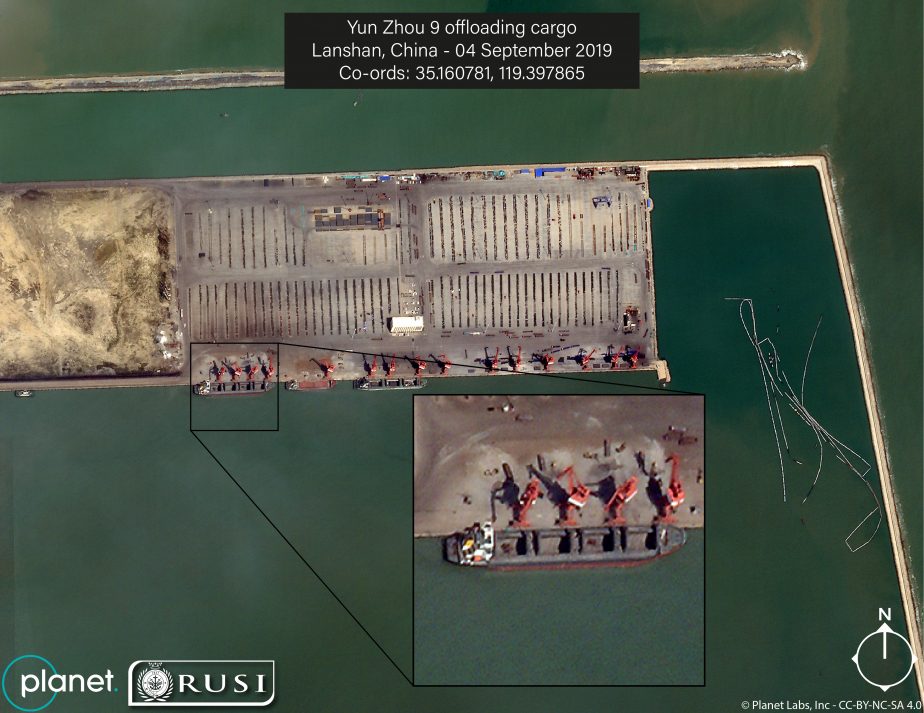

On September 5, high-resolution satellite imagery taken by Maxar Technologies shows the three vessels and a number of large, manned floating transshipment platforms designed to move commodities between vessels at sea in risky operations known as ship-to-ship (STS) transfers. These STS transfers have become a staple among North Korea’s sanctions-busters as they have sought to avoid scrutiny by transferring oil, coal, and other cargoes away from port and in the open ocean where they are difficult to detect with satellite imagery.

While it remains unknown how this complex operation was organized and coordinated, high-resolution imagery shows the Chinese-flagged vessel sitting high in the water with her cargo bays open. Berthed to her starboard is the North Korean-flagged Jin Hung 9, with a floating transloading platform between them. On its port side, another floating transloading platform is berthed alongside the Yun Zhou 9, while the Ever Glory appears to be maneuvering itself into position to berth next to the platform.

The Chinese-flagged Yun Zhou 9 conducting an STS transfer with the Jin Hung 9 and Ever Glory. Source: Maxar Technologies, RUSI Project Sandstone.

Two kilometers to the northeast, another North Korean vessel named the Boun 1 was berthed next to another floating transloading platform, indicating it is also preparing to conduct an STS transfer of cargo.

AIS data suggests that the entire STS operation took around 24 hours to complete, after which the Yun Zhou 9 set course to sail around Shandong peninsula and return to Bohai Bay.

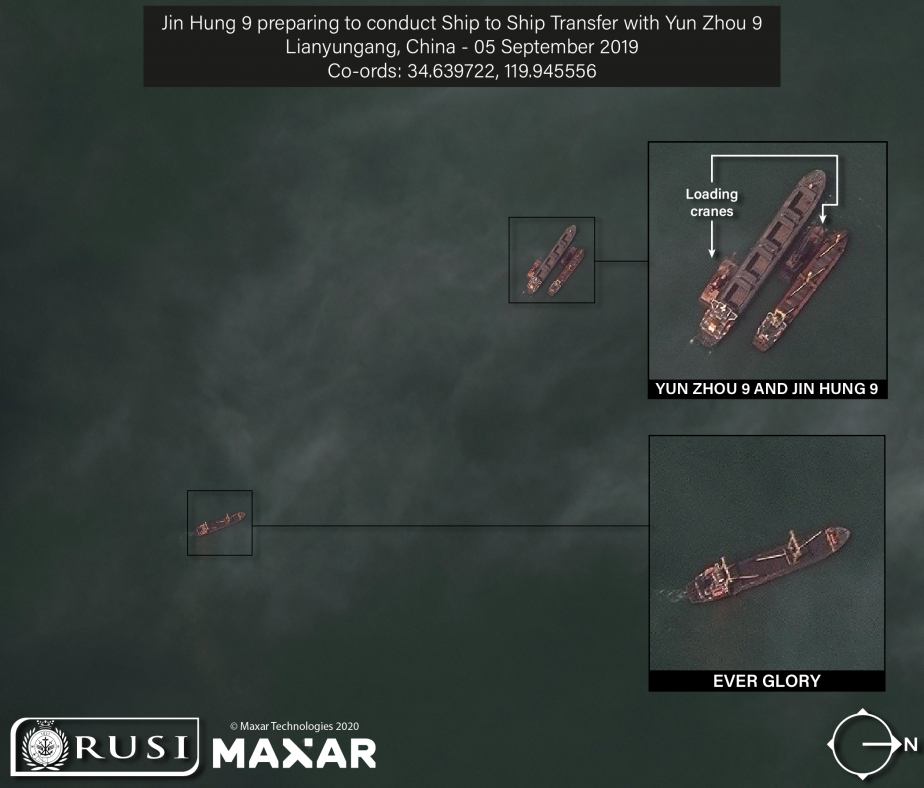

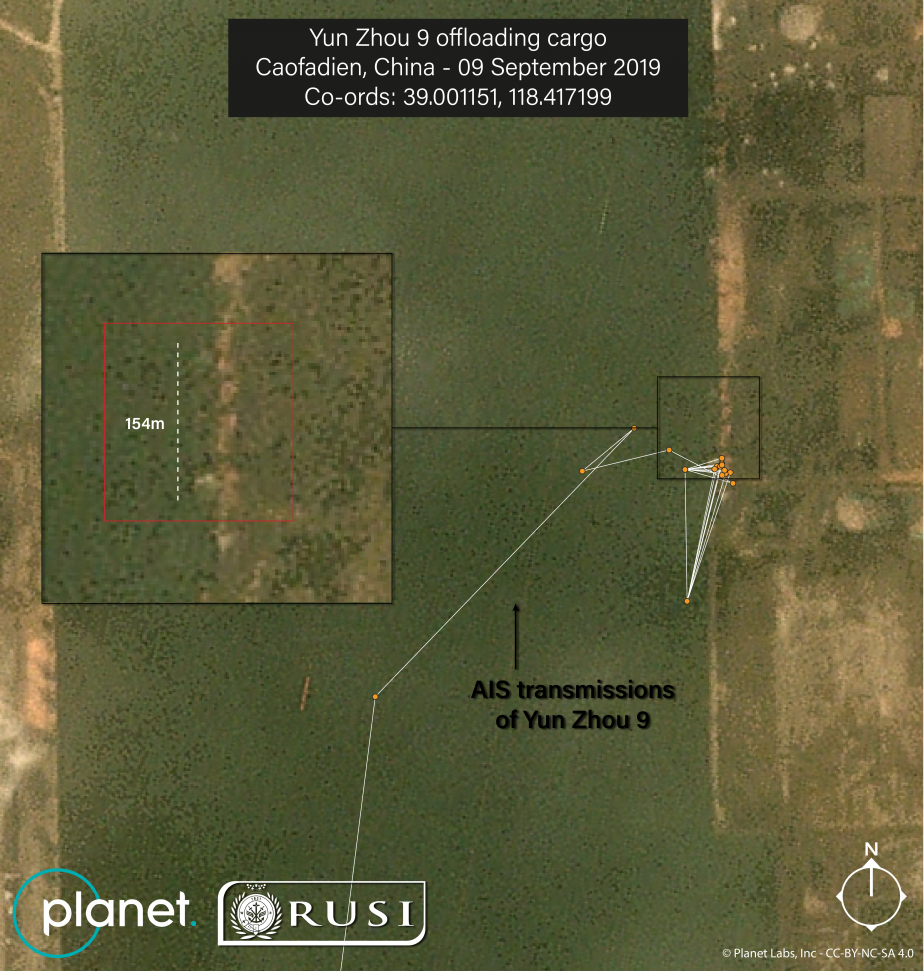

The Yun Zhou 9 arrives at the port of Caofeidian, China on September 9. Source: Planet Labs, Windward, RUSI Project Sandstone.

Imagery and AIS data reveals that after this STS transfer on September 9, the Yun Zhou 9 arrived at the port of Caofeidian, Hebei, to offload its cargo at a general terminal owned and operated by Tangshan Caofeidian Steel Logistics Co Ltd (唐山曹妃甸钢铁物流有限公司), a subsidiary of HBIS Group International Logistic Company (河钢集团国际物流有限公司) and ultimately owned by HBIS Group Co Ltd (河钢集团有限公司) – a Chinese State-Owned Enterprise and one of the largest steel producers in the world.

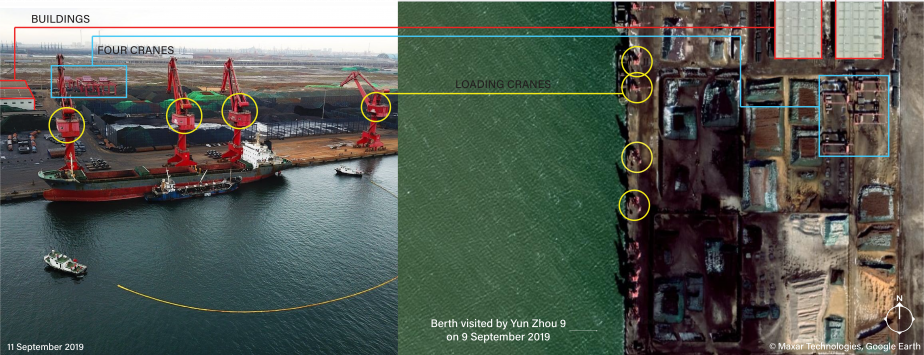

A comparison between open-source imagery and satellite imagery of the Caofeidian terminal owned by Tangshan Caofeidian Steel Logistics. Source: MarineCircle, Maxar, RUSI Project Sandstone.

Open source and high-resolution imagery of this terminal shows it is used to handle coal and other bulk commodities. In 2014, Tangshan Caofeidian Steel Logistics registered to the Department of Natural Resources of Hebei Province the use of sea around the current terminal location. The first phase of the terminal was completed in 2016. The general terminal – which required an estimated total investment of 1.5 billion RMB – includes new 50,000-ton and 20,000-ton berths, as well as supporting facilities, adding 10.49 million tons of annual cargo throughput capacity to the Tangshan port area. There is no evidence to suggest Tangshan Caofeidian Steel Logistics or its parent companies had any knowledge of the illicit origin of the cargo onboard the Yun Zhou 9.

Mystery of the Yun Zhou 9

Built in 2009 by a Chinese shipyard, the Yun Zhou 9 was delivered to a company named Weihai Senior Master Shipping (威海老船长航运有限公司) in October that year. Based out of a room in Huancui District in the city of Weihai, the company shared an office with the similarly named Senior Master International Ship Management (威海老船长国际船舶管理有限责任公司), itself owned by the director of Weihai Senior Master Shipping. This company had for years operated a vessel named the Surplus Ocean 1, a now-broken up bulk carrier but once regular visitor to North Korean waters, indicating its owners had a long-running trading relationship with the country.

However, while this might usually help explain the sanctions-busting trip of the Yun Zhou 9 in August 2019, records from the Qingdao Maritime Court show the ship was seized at some point in 2018. Then named the Lao Chuan Zhang 717 (老船长717轮), the ship was auctioned on November 14, 2018, and purchased by an undisclosed buyer for 33,888,000 RMB ($4.78 million). The buyer then renamed the vessel and flagged it to China. Despite this, the International Maritime Organization’s public database holds no record of the ship’s owner.

The Yun Zhou 9 as advertised for auction after being seized by Qingdao Maritime Court. Source: Taobao.

Ten days later, on November 24 the Yun Zhou 9 set sail from Dalian to Chengshan township, Rongcheng, Shandong province. In fact, since January 2019, the ship has been active in domestic coastal trade, transiting between ports in Bohai Bay and those on the Chinese eastern coast as far down as Zhejiang province.

However, while port call records for Hebei’s Maritime Safety Agency show the ship calling at ports in that province throughout 2019 under the name Yun Zhou 9, the identity of her new owners and those responsible for importing North Korean coal in violation of UN Security Council resolutions remains a mystery.

While Pyongyang may have temporarily recalled its fleet as a result of the pandemic sweeping the globe, as the crisis subsides North Korea’s smuggling operations will once again rely on vessels like the Yun Zhou 9 to deliver sanctioned commodities to China and further afield.

This investigation was conducted by Project Sandstone — a RUSI initiative to systematically analyze and expose North Korean proliferation and illicit shipping networks.

This article is presented by Diplomat Risk Intelligence, The Diplomat’s consulting and analysis division. To learn more about DRI, click here.