I have often wondered how Sajid Hussain read so much. From Franz Kafka and Joseph Heller to Arundhati Roy and Mohammed Hanif, he did not miss any of their works. In fact not only did he read novels thoroughly, he also reread many of them. And if by any chance he found out that he had not read something that was meant to be read, he would grab it and finish it as soon as he could.

I felt a kind of triumph when, just last year, I was talking to him about a book I was reading. It was by Dr. Viktor Frankl, and was a real page-turner, chronicling the writer’s experiences as a prisoner in the Nazi concentration camps. I discovered Hussain had not read Man’s Search for Meaning. Finally, there was something that I was reading that he – my mentor — had not touched. But never one to leave a good book behind, just a few days later, Hussain messaged me saying yes, indeed, it was a good read.

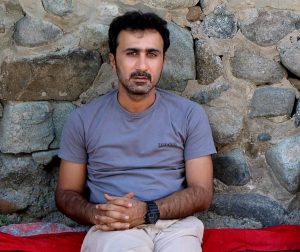

He was a voracious reader and that is probably why Hussain was also an excellent writer and a brilliant journalist. “If you want to do justice with writing, you must read, read, and read,” he often said. He was adamant on this formula as he taught me the ins and outs of journalism.

But when a new wave of the “kill and dump policy” came about, and the issue of enforced disappearances once again engulfed Pakistan’s restive province of Balochistan, Hussain had to flee the country in 2012. For many years after that he lived like a nomad, a refugee, spending some time in one country and then moving to another.

It was not an easy decision, leaving behind his friends and family back home – his wife, 9-year-old daughter, and 5-year-old son, whom he loved dearly. During one of our first chats, he told me, “I was forced to leave.” Hussain spent months and years in exile in Oman, Dubai, and Uganda before ending up in Sweden, one of the world’s safest countries, in 2017

But after escaping Pakistan because of safety concerns, today he has mysteriously gone missing in Sweden.

On March 28, 2020, the online news portal Balochistan Times announced that Hussain, who was its chief editor, had gone missing on March 2 from Uppsala, a city about 70 kilometers from Stockholm.

Hussain’s disappearance is puzzling for everyone who knows him well. Whether it was related to his work or to rising numbers of missing people in the Scandinavian nation, no one can piece together what has happened to him.

A Final Farewell to Balochistan

Pakistan is rated among the most dangerous countries for journalists in the world. It seems to be the worst for journalists like Sajid Hussain, who come from areas such as the province of Balochistan, which is riven by insurgency; a place where journalists have been trapped between the devil and the deep blue sea.

Hussain also reported on controversial topics, such as human rights abuses, insurgency, politics, and the drug trade. He served as assistant editor and city editor in The News International, the largest English daily in Pakistan. He also wrote editorial articles for the paper.

In September 2012, Hussain was helping a Reuters’ journalist write a story on enforced disappearances during a UN team visit to Balochistan. The team was focusing its work on human rights abuses in the province. Then trouble ensued.

A close friend of Hussain, who requested anonymity, narrates the story: “Sajid was sitting with the journalist in his room at a hotel in Quetta [the capital of Balochistan] when some security officials came and knocked on the door.” The foreign journalist asked Sajid to leave using another door, which he did, narrowly escaping before the security officers could get a hold of him.

“As soon as he came back to his flat in Quetta, he emailed a chapter of his book to me,” says his friend. The email reads, “Remember! This is the rough draft. Don’t make it public at any cost. If in any case something happens to me, hand it over to my daughter, when she is grown up.”

Within a week of the incident, Hussain left Pakistan for unknown territory, leaving behind his wife and daughter, who was 1 year old at the time.

“[The character] Yossarian from Catch 22 has stayed with me,” Hussain told me in a previous interview for Dawn. “His only goal is to not get killed in the war. Not getting killed in Balochistan is the best service you can do to yourself.”

In a similar case, journalist Malik Siraj Akbar, who served as the former bureau chief of Daily Times in Balochistan, was also was forced to leave the country because of his work.

It was a crucial time in the province when Hussain and Akbar fled. The insurgency was ongoing — a full-fledged war between the Pakistani armed forces and the insurgents had torn the province apart. The issue of enforced disappearances arose from that problem, and so did the killings of many political workers, activists, and journalists. The insurgency is still alive in the region, but the intensity is not the same after the security establishment carried out a brutal crackdown.

Akbar, speaking to The Diplomat, remembers that back then, the media had been “relatively free” outside of Balochistan, particularly in Pakistan’s large cities.

“Now, journalists say journalism in big cities like Islamabad and Karachi is as risky as it used to be in Balochistan,” Akbar says. “The PTI government is seemingly at war against the media. Credible editors who have seen Pakistan under martial law say things are definitely worse these days.”

Under the premiership of Imran Khan, the news media seems to be a favorite target of the government. Only recently Mir Shakil Ur Rehman, the owner of the largest media network, the Jang group, was arrested in a 36-year-old case. He is now in prison and activists and journalists are calling it a personal vendetta. Khan seems to be catalyzing the death of Pakistan’s press freedom.

Attack on a Dissident or a Swedish Missing Person Case?

Amid these difficulties in Pakistan, Sajid Hussain vanished in Sweden.

On March 2, Hussain said goodbye to his friends and shifted to his new apartment — a private student accommodation in Uppsala. He was enrolled in a master’s program at Uppsala University. He was also working on a project in the Iranian Department of the same university for the promotion and development of the Balochi language.

His friend Abdul Malik last said goodbye to Hussain that same morning, before leaving for Stockholm himself. Malik did not in his wildest imagination think that he would soon be starting a Twitter campaign to #FindSajidHussain with other friends and activists.

On March 30, the Committee to Protect Journalists (CPJ) issued a statement about Hussain’s disappearance and urged the Swedish authorities to make every effort to locate him and to ensure his safety. The International Federation of Journalists and its affiliates in both Sweden and Pakistan issued a similar statement on April 2.

Reporters Without Borders (RSF) on March 30 also issued a press release on Hussain’s disappearance. The RSF statement highlighted the targeting of overseas journalists by the Pakistani security agency in other cases and expressed its suspicions over their involvement in Hussain’s disappearance.

But Shehnaz Baloch, Hussain’s wife, tells The Diplomat they do not want to accuse anyone without facts. “All we want is for the Swedish authorities, particularly the police, to look into the matter very seriously and actively. As for going into isolation on his own, I do know that he will never leave anywhere without informing us.”

In a statement, published in Balochistan Times, the family also says that “it is too early to accuse anyone.”

Even in Sweden, authorities say thousands go missing each year.

Jenny Johansson, case officer at Missing People (Sverige), an NGO that works with the Swedish police to find missing people, said that “around 9,000 people go missing in Sweden [each year]. Most of the Swedish people go missing with fragile mental health and may even be involved in crime or suicide.”

But she admits that since Hussain is not Swedish, the case becomes unique due to his background. “We are not sticking to one aspect of the case but are looking into his disappearance from all angles. The case is baffling, and we are clueless.”

The case really is perplexing. Law enforcement officials have so far not found a clue after dredging lakes and closely searching forests and woods for more than three weeks. Very recently, a month after Hussain’s disappearance, the police put up posters about the case and shared the news on TV as well. They are asking the public if anyone has seen Sajid Hussain on or after March 2.

The investigation officer for the case went on leave at the end of the last week and is not set to return until Wednesday. The delay is a source of great anxiety for Hussain’s family, who keenly feel the passing of each hour.

Daniel Bastard, the head of the Asia-Pacific desk at RSF, said that enforced disappearances — or worse — are a new way to prevent exiled journalists from expressing their views. The murder of Jamal Khashoggi in Istanbul’s Saudi consulate, and the way those behind the crime got away with it with full impunity, has emboldened many security agencies.

Over the last few years, attacks on exiled journalists in Europe have surged. Bastard tells the Diplomat, “No later than in November 2019, the Iranian intelligence agency launched a coordinated program of harassment and threats against several Iranian journalists based abroad — especially in Britain — and working for news outlets such as the BBC, Radio Farda, the Iran International or Manoto TV channels. China too, has a record of abducting journalists abroad, but mostly in Asian countries.”

A Vanished Writer’s Haunting Words

If the Sajid Hussains of this world are going to be silenced, then the message being sent is very violent.

Hussain was a ruthlessly honest writer, sensitive, imaginative, and with a political sense. His uncle, Ghulam Mohammed, who was killed in 2009, belonged to a hardcore nationalist political party, but Hussain’s emotions never overburdened his journalistic integrity. Baloch nationalists, separatists, and the military establishment — none escaped the wrath of his pen.

His sensitivities were clear not only in his journalistic writing but also in his literary works. He lamented old traditional ideas and approaches in the Baloch society, tribalism, and emotional politics.

Hussain also ran a personal blog, titled “Sajid Baloch From Terra Incognita,” where he wrote expansively about various topic from Baloch art and culture to sociopolitical stories.

To make his point about the absurdity in the world, Hussain would quote authors such as Franz Kafka. He was truly obsessed with Kafka, believing in everything he stood for. He was also terribly fond of Mohammed Hanif and his dark humor. He often reread Hanif’s works.

Hanif himself spoke to The Diplomat about Hussain, commenting, “I find it strange that he was forced to leave [the] country because so many people close to him disappeared. And now he himself has disappeared in Sweden, where he had just started a new life. I am worried sick.”

Indeed, the irony is almost unbearable. Hussain narrated the stories of enforced disappearances honestly and truthfully, giving a human face to the political scenario.

Some of his words continue to torture me today, after his own disappearance.

In a previous interview for The Diplomat, Hussain spoke about missing persons. “The dead do not haunt me as much as the missing do,” he said. “To tell the truth, I feel relieved when I hear about the discovery of a missing person’s body. But the stories of those languishing blindfolded in tiny, dark cells for years make me avoid dark, congested places.”

Now it is Hussain’s disappearance that is haunting his friends, family, and colleagues. Not knowing about the whereabouts of a friend or a family member is torturous. Balochistan is the home of around 6,000 missing persons; that means thousands of families are living in torture. Hussain was a voice for these voiceless victims — and now they want their voice to come back.

Even more haunting is one chapter of Sajid Hussain’s book, meant for his daughter. The chapter involves a conversation between a doctor and an ambulance driver, who has picked up a mutilated body. An unidentified body.

Shah Meer Baloch is a journalist based in Pakistan. He has had his work published in New York Times, The Guardian, Deutsche Welle, The National, The Diplomat, Daily Dawn, Firstpost, Herald magazine, and Balochistan Times.