A series of developments in recent weeks across Asia’s key security flashpoints reinforces an important reality: Even as key regional governments are understandably consumed by the global coronavirus pandemic which ought to foster a more collaborative environment, managing key conflicts and tensions is likely to continue to prove challenging and at times even more so in the coming months.

While Asia has seen so-called “long peace” since 1979 – a term often loosely used in order to characterize the steep decline in inter-state conflict relative to the past (which, notably, does not include intra-state conflict or tensions) in the region since that time – the region is still home to some key flashpoints, with the most prominent ones being North Korea, the East and South China Seas, and tensions across the Taiwan Strait, along with other unresolved territorial and maritime disputes as well that are less in the spotlight.

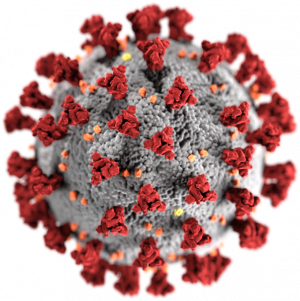

Global pandemics are the sort of transnational threat that raise hopes that cooperation can bring about a temporary pause on all sides on major conflicts and flashpoints – particularly given the alignment of threat perceptions on the common challenge at hand and its intensity and scope which requires extensive collaboration to mitigate and manage, let alone eventually eliminate. COVID-19 has understandably brought about these aspirations as well, with UN Secretary General Antonio Guterres last week calling for a ‘global COVID ceasefire’ of sorts being an example of this.

Guterres’ call is a noble one to be sure, and, to a certain degree, there may be a de-escalation or deprioritization of some conflicts or tensions by certain actors out of wisdom or sheer limited bandwidth, such as in active insurgencies as we’ve seen. But with respect to Asia’s key flashpoints, given enduring realities – including the centrality of the handling of these flashpoints to the national interests of these nation states; the risk of accidents and miscalculations occurring as actors are consumed by COVID-19; and the potential for geopolitical competition to spill over into other areas – one should be wary about understating the challenges of hitting the pause button and maintaining it in the coming months.

First, some governments remain undeterred from achieving their initial objectives with respect to certain flashpoints in spite of COVID-19, and may in fact seize on this as a window of opportunity. North Korea’s firing of ballistic missiles over the weekend and its continued confrontational rhetoric is an important reminder of this point – Pyongyang has been keen to ensure that it is not forgotten amid the coronavirus. Meanwhile, in the South China Sea, even as Southeast Asian states contend with the fallout from the coronavirus whose initial epicenter was in China, Beijing sees no contradiction in providing COVID-19 assistance to burnish its image and continuing to incrementally advance its claims in the South China Sea to the detriment of the four ASEAN claimants – Brunei, Malaysia, the Philippines, and Vietnam. Baked into that is the possibility that China may seize on the fact that these countries are consumed by COVID-19 to undertake a series of actions designed to bolster its position and test the resolve of rival claimants.

Second, the risk of accidents or miscalculations that could then blow up into wider tensions remains and may in some cases be at an increased level. The collision between a Japanese warship and a Chinese fishing vessel in the East China Sea on Monday serves as a timely case in point. While details still remain unclear, given the fact that previous such incidents have sparked wider diplomatic crises as we saw back in 2010 between Tokyo and Beijing, it reinforced the fact that these developments could recur amid a much more uncertain COVID-19 context.

Third, geopolitical tensions either made worse by COVID-19 or intensifying within a broader context may spill over into specific flashpoints. Of particular note in this regard is U.S.-China rivalry, which has shown few signs of easing amid the coronavirus pandemic for now and could easily spill over into other flashpoints such as the Taiwan Strait. And beyond the U.S.-China lens, there are other dyads that remain important to watch, including India-Pakistan relations where though things remain calm for now, sudden incidents can quickly turn into tensions and then conflict as both countries contend with the ongoing fallout from COVID-19. Ongoing developments in 2019, including Japan-South Korea tensions and issues with respect to the various disputes between individual Southeast Asian states, also suggest that caution is warranted with respect to this as well.

Of course, attention to these developments should not be read to suggest that the global coronavirus challenge necessarily or inevitably makes the management of Asia’s security flashpoints more difficult – peace and conflict management are ultimately what countries choose to make of it within the context they face. But it is to say that in spite of the more collaborative environment that COVID-19 ought to foster, the realities of putting aside or deemphasizing flashpoints is likely to prove much more challenging than the aspirations of doing so. That is worth keeping in mind in the months.