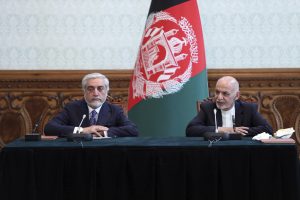

Out of the four presidential elections Afghanistan has conducted since 2001, only one has gone undisputed. The remaining three have either ended in a political crisis or resulted in some kind of power-sharing deal. The result of the 2009 elections was not accepted by Hamid Karzai’s runner-up, Abdullah Abdullah, who claimed the election was full of corruption and fraud. The 2014 election, with Ashraf Ghani declared the winner but Abdullah again disputing the results, ended in the formation of the National Unity Government (NUG). The third presidential election conducted last September led to the formation of another coalition government between the same two rivals, Ghani and Abdullah. After months of negotiations, they both agreed on a deal that gave Abdullah leadership of the peace process and a 50 percent share in the cabinet.

While the 2014 election that led to the creation of the NUG was riddled with fraud and corruption, the resultant peaceful transfer of power from one government to another was unprecedented in Afghanistan’s history. Also unprecedented was the election of a Western-educated technocrat as the country’s president. Afghans hoped that an outsider with no ties to tribal leaders and with expertise in fixing failed states would be in the best position to bring peace and development to Afghanistan. Unfortunately, they were in for a painful surprise.

Looking back, Afghanistan was comparatively better off in the years prior to the formation of the NUG. The insurgency, while threatening, did not pose an existential threat and the economy was in a better shape. But the bulk of U.S. troops withdrew from the country in 2014, just as the NUG was taking power. As a result, during the NUG’s term the Taliban expanded their area of control, were able to take over three provincial centers, and a posed significant threat to the others across Afghanistan. Today, the Taliban are in control of or contesting more territory than at any point since 2001. Civilian deaths and the number of Afghan security forces killed in battle have exponentially increased as well. President Ghani, in an interview last year, admitted that over 45,000 security forces had been killed in battle since 2014.

The unity government also marked the immigration of thousands of Afghans to other countries and the displacement of around 1,174,306 internally. The number of Afghans living below the poverty line increased from 38 to 55 percent under the NUG’s watch — a government whose stated goal was to fulfill the “aspirations of the Afghan public for peace, stability, security, rule of law, justice, economic growth, and delivery of services.”

The NUG turned out to be a disappointment because it was anything but united. It was riddled with internal conflicts, corruption, and violence. Almost none of the major promises stipulated in the NUG agreement — including electoral reform, organizing a Loya Jirga to discuss the position of executive prime minister, and conducting district elections — were realized. A study found that out of the 18 promises, only one was achieved in the first three years of the NUG. The government eroded people’s trust in democracy and public institutions and widened the gap between the government and the governed. Research shows that Afghan confidence in public institutions substantially decreased during the unity government.

The NUG, however, provided some important lessons that the current government, which also came into existence through a power-sharing deal, could use to avoid past mistakes.

Oversight and Implementation of the Agreement

Unlike the NUG agreement, the new power-sharing deal stipulates an oversight mechanism. It calls for the establishment of an oversight and mediation commission and a joint technical team to identify and prevent instance of violations of the agreement. These two yet-to-be-created bodies will have the important job of monitoring the compliance of Ghani and Abdullah with their joint agreement and providing recommendations when they violate it. If the oversight commission has some of the leaders who mediated the agreement as its members, its chances of making both sides stick to the agreement will increase, thereby increasing the likelihood of the government’s success. These mediators are respected by the people and are listened to by the leaders.

Electoral Reform

In a study conducted on the heels of the formation of the NUG in 2014, an overwhelming majority of Afghans (92 percent) recognized significant flaws in the 2014 electoral process and made strong calls for electoral reform. Unfortunately, electoral reform was not at the top of the agenda of the two leaders during the first three years of NUG. They started to pay attention to it only toward the end of the government. For more Afghans to participate in future elections, the government must make good on its promise of electoral reform as envisaged in the political agreement. What people want is not just dismissal of the electoral officials, as has happened in the past, but a real and comprehensive electoral reform. Afghanistan’s nascent democracy will likely experience another crisis — from which it may not be able to recover if people’s trust in the electoral process is not regained

It is also important for the government to conduct district council and mayoral elections as stipulated in the agreement. District councils would complete the quorum for a Loya Jirga that will be required to ratify a possible deal with the Taliban, while mayoral elections will improve service delivery and pave the ground for decentralization of power.

Decentralization of Power: The current unitary form of government has not helped Afghanistan much. It has led to a fight for power among the elites and influential leaders, increased corruption and violence, and brought about a culture of impunity among various political players. Given the diverse ethnic make-up of Afghanistan, the only reasonable form of government capable of providing security and development is a federal government. The new government is in good position to start the decentralization process by slowly devolving power to the provinces and letting them be in the driving seat of development, as they are in much closer contact with the people than the central government.

Mutual Cooperation With the Parliament: The NUG did not enjoy a lot of support from the parliament. In fact, the whole period of NUG rule was marked by conflict between the two branches. Half of the NUG ministers could not secure vote of confidence from the parliament for the first two years. Even when the ministers did finally get a vote of confidence, they allegedly paid heavy sums in bribes to the lawmakers in return for their vote. The new government has an opportunity to turn the parliament into an ally by establishing a working relationship that is beneficial for the Afghan people.

Addressing these lessons could regain people’s trust in democracy and help prevent Afghanistan from plunging into another political crisis.

Hadia Haqparast is a democracy and governance expert and a Fulbright scholar with a Masters degree in Public Administration. She has over a decade of experience in working with development projects in Afghanistan.