After Canberra called for an independent, international inquiry into the origins and handling of COVID-19 in April 2020, its bilateral relations with Beijing have reached a nadir. China’s ambassador to Australia, Cheng Jingye, warned of a potential Chinese consumer boycott against Australian products and services if Canberra insisted on pushing for an international investigation. China then imposed an 80 percent import tax on Australian barley, and suspended beef imports from four Australian abattoirs. In response, Canberra indicated that it would consider logging a complaint against China with the World Trade Organization over the barley tariffs.

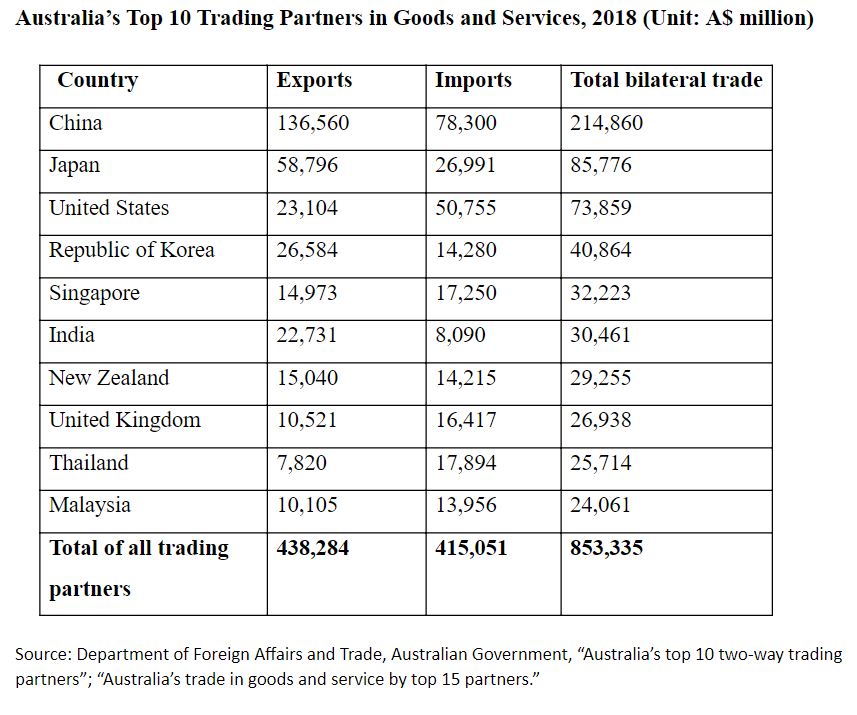

The current trade tensions have been widely seen as a tit-for-tat strategy retaliating against Canberra’s call for an independent investigation into the COVID-19 pandemic. However, this also exposes Australia’s preexisting economic vulnerability to China. Since 2009, China has been an indispensable trading partner for Australia due to its insatiable demand for mineral resources and agricultural products. Excessive reliance on China for economic growth has become a potential security risk for Australia. In 2018, Australia’s trade surplus with China (A$58.26 billion) amounted to more than 250 percent of its total trade surplus (A$23.23 billion), indicating that Australia ran a trade deficit with many of its trading partners (such as the U.S., the U.K. and ASEAN). China accounted for more than 31 percent of Australia’s total exports, and Australia’s bilateral trade with China (A$214.86 billion) was also much larger than that with its second trading partner, Japan (A$85.78 billion).

Many have agreed that Australia is too dependent on China economically but we need to have a cool-headed assessment of just how fragile Australia is to China’s economic pressure. Second, while this paper is not proposing any decoupling, which has been labelled a “zombie economic idea” by some, it explores how Australia can reduce its dependence and mitigate the risk of its economic vulnerability over the longer term.

Theoretically speaking, Australia should insure itself against external economic coercion in order to reduce its economic dependency on China while protecting its economic growth. However, is it readily feasible for Australia to find new markets to diversify the destinations of its exports? Can more free trade agreements with other countries help Australia reduce its economic vulnerability?

How Effective Has Chinese Economic Pressure Been?

Australia-China trade relations could broadly divide into two categories: primary products (including iron ore, coal and agricultural products) and service industry (such as tourism and education). China issued a safety warning to all Chinese students in Australia in 2018 after an accusation by then-Minister for International Development and the Pacific Concetta Fierravanti-Wells of China’s infrastructure aid to the Pacific as “white elephant” projects. Beijing undertook a year-long anti-dumping investigation into Australian barley in the same year after Canberra’s decision to expand its naval base on Manus Island in order to counter China’s growing influence in the region. In this round, Ambassador Cheng also focused on the Australian agricultural industry but not mineral products. Why?

China heavily relies on iron ore for its steel industry (iron ore prices are going up again because of the resumption of production in Chinese steel mills), and Australia has leverage in this area. Australia is not only one of the largest iron ore producers of the world, but also geographically closer to China than most others. The shipping costs are arguably much lower than from the world’s second largest iron ore producer, Brazil. The COVID-19 pandemic may lead to an economic collapse of the Latin American country. Thus Australia will continue benefiting from Chinese demand for its mineral resources in its determination to boost economic growth after the country’s GDP contracted by 6.8 percent year-on-year in the first quarter of 2020.

In the education sector, will Chinese students heed the “call” by the Chinese ambassador not to go to Australia? As a country in the Anglosphere, Australia’s education sector has an inherent advantage in using English as the medium of instruction. On paper, Chinese students could choose Canada, New Zealand, the U.K. and the U.S. instead of Australia. But Australia still maintains an advantage, in addition to geographical proximity to China. After the COVID-19 pandemic, will Chinese students and their parents feel it safer to study in the U.K. and the U.S., which are among the hardest-hit countries? Due to the escalating Sino-U.S. conflict, Republican lawmakers in the U.S. have called for tightening the issuance of student visas to Chinese students and researchers.

Although China’s economic sanctions may not be implemented permanently and not be effective, it makes good sense for Australia to take steps to reduce its economic dependency on China and to protect its economic growth.

How to Flatten the Curve of Excessive Reliance on China for Economic Growth?

Let us examine what has happened to the Australian trade balance after signing FTAs with major economies such as the U.S. and the ASEAN members. The Australia-U.S. FTA, which came into force in 2005, indeed helps American goods and services enter the Australian market. In 2018 Australia’s exports to the U.S. merely accounted for 5.2 percent of its total exports and Australia ran a trade deficit of more than A$27 billion with the U.S. that year. The ASEAN-Australia-New Zealand FTA came into force in 2010 with six ASEAN countries and by 2012 with all of the 10 ASEAN members. Australia has also signed bilateral FTAs with Indonesia (2019), Malaysia (2013), Singapore (2003) and Thailand (2005). Three of them (Malaysia, Singapore and Thailand) were among Australia’s top 10 two-way trading partners in 2018. However, similar with the U.S., Australia ran a trade deficit with ASEAN as a whole, and with Malaysia, Singapore and Thailand (see table below).

There are at least three steps Australia can take to reduce its economic dependency on China and to protect its economic growth. First, Australia should carve out its own niche in the tertiary sector to turn its trade deficit to a surplus. Australia may consider promoting ecotourism and education to ASEAN countries. Second, Australia could attempt to clinch new FTAs with other economic partners in the region, including Taiwan, which also faces a similar dilemma as Australia – how to lessen economic dependency on China without harming its economic growth. With its New Southbound Policy, Taiwan is engaging more with Southeast Asia economically. Could Australia consider widening its net of key trading partners to include Taiwan? A third step would be for Australia to upgrade its industrial structure by transforming it into an industrial economy, relying less on exporting raw materials and agricultural products. Turning its abundant raw primary resources into higher value-added manufactured products would not be aimed at completely decoupling the Australian and Chinese economies, but to flatten the curve of its dependency.

Lai-Ha Chan is a senior lecturer in the Social and Political Sciences Program, Faculty of Arts and Social Sciences, University of Technology Sydney, Australia. She was a Fung Global Fellow (2016-2017) at the Princeton Institute for International and Regional Studies, Princeton University, New Jersey. Her current research centers on the impact on regional order of China’s economic statecraft and infrastructure investment; and on Australia’s hedging policy in the Indo-Pacific.