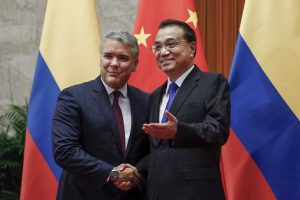

Chinese entrepreneurs have closed more contracts in Colombia during the past six months than throughout the previous four decades of relations between the two countries. 2019 saw Colombian President Ivan Duque pay a state visit to China, commemorating 40 years of bilateral relations. Beyond the usual business-related engagements and the signing of treaties, the event saw the Colombian leader navigate a barrage of questions regarding the future relations of the two countries. In an interview with Beijing-based media giant Caixin, Duque highlighted the aim of making Colombia “the Golden Gate” for Chinese enterprises and its people in South America.

For years, Colombia has witnessed close neighbors Ecuador and Venezuela attract considerable investment from China, while standing by as Washington’s most powerful ally in the region – a position that, for many decades, has meant having among the lowest Chinese investment figures in the region. Recent months have seen the trend reverse, however, as Chinese and Colombian officials are on the cusp of signing an agreement to strengthen trade ties and further Chinese infrastructure investments in the country. Until the pandemic, these investments had not received much scrutiny or examination, particularly with regards to future great power relations within the region.

The agreement, which is being finalized, will include projects labelled under the Belt and Road Initiative as well as various bilateral agreements ranging from politics to culture. It proposes the development of Colombian 5G networks under the mantle of Chinese tech giants Huawei and ZTE. And perhaps most notably, last November witnessed Colombian lawmakers award the often-frustrated and delayed contract for what will be Bogota’s first metro-rail system. The winning firm, a Chinese consortium by the name of APCA Transmimetro, pitched the lowest-cost proposal, satisfying all the metrics prescribed by the local budget. But the deal would also pave the way for more, including ventures in renewable energy, technology, and agriculture. China is also looking to import major goods such as flowers, meats, and dairy products.

In the Colombian context, Chinese investment is linked to two major conditions — the multimillion-dollar local business environment that allows for the awarding of large industrial contracts, such as the Bogota metro, and the fact that the country has had, prior to the COVID-19 crisis, some of the best economic growth metrics in the hemisphere. With an increase of 3.3 percent last year, Colombia’s growth was the fastest among the major Latin American economies. Finally, Colombia has the unusual characteristic of possessing — unlike many neighboring states — a stable political environment that has not seen its government suffer any major revolts or turmoil.

Ironically, these developments come at a time when China’s relations with left-wing governments like Venezuela’s are being questioned internally. The China Institute of International Studies’ Blue Book reports have been increasingly negative toward left-wing governments in South America, and issued sharp criticisms of the economic performances of Bolivia and Venezuela. As a result, China has been warming up to right-wing leaders across the continent — including in Argentina and Brazil. In the case of Colombia, it was previously believed that President Duque would continue normal relations with Washington via the status-quo ideology of the Centro Democratico party, which belongs to the far-right side of the spectrum, and is led by former President Alvaro Uribe — who was himself the architect of the country’s prosperous rapprochement with the United States at the start of the 21st century. In light of declining foreign direct investment (FDI) from the U.S., however, local business leaders have urged greater Chinese participation in the country.

In the past, Colombian foreign policy in Asia has been reactionary, instead of strategic. And while closer relations have begun to emerge by emulating the strategies of Chile and Peru, Colombia’s relationships with Asia-Pacific countries have been otherwise quite limited. But with the Trump administration voicing Colombia’s dispensability, including sharp criticisms over its handling of drug trafficking as well as declining FDI, the latter now finds itself seeking diversification and economic reassurance. China is gladly willing to fulfill that role.

The Chinese strategy for the region was updated in recent years into a multifaceted plan named 1+3+6, meaning one “plan,” three “engines,” and six “attractive industries.” The strategy consists of investing in energy and resources, infrastructure, farming, manufacturing, science, technology, and information technology.

These economic endeavors have been paired with increased public diplomacy efforts aimed at reinforcing China’s “soft power” in the region. Under President Xi Jinping, Chinese Communist Party (CCP) doctrine has championed the importance of “discourse power,” or the mobilization of the story of China and its values as means to shape outsider preferences. State-run media outlets, such as China Global Television Network, Xinhua, China Daily, People’s Daily, and Global Times, have increased their presence in Colombia, and further been used — especially Xinhua — as de facto arms of Chinese intelligence. The outlets are leveraged to seek new and innovative ways to propagate the CCP’s message globally, while denying space and attention to adversarial narratives. A highly scrutinized video, which appeared on the same social media platforms that are currently banned on the Chinese mainland, presents a case of narrative manipulation through didactic Lego-like figures as means to bolster China’s image in face of the pandemic, while at the same time disparaging that of the United States.

These public diplomacy maneuvers surgically pick and persuade local officials. Beijing’s ambassadors often broadcast the same messages in tandem with one another across multiple countries, differentiated only by the local language. China’s ambassador to Colombia, Lan Hu, reiterated his country’s intent to construct cultural centers in Colombia with Chinese money. These centers would serve to attract and create a Chinese diaspora within the country, which remains among the smallest in the region. Under the context of the Bogota Metro project — which would see an influx of 1,300 Chinese workers into the city — his goal has inched closer to its intent. Indeed, a local council member proposed that Mandarin be taught as a foreign language in schools as a new cultural pivot.

This is in spite of the questionable role of China’s investments, given that Chinese aid can ferment corruption and low standards of quality assurance. Since 2002, only half of the 150 South American infrastructure projects led by China have been completed. In Colombia, the much-lauded metro deal has already begun to show cracks, with a construction delay of two years added to the initial eight, coupled with increased scrutiny over the role of certain local actors.

South America has in the past been labelled, if somewhat crassly, as “America’s backyard.” But among countries such as Peru, Brazil, Chile, and Argentina, perhaps no country completes the analogy more than Colombia, whose position in the region has been likened to that of Israel in the Middle East — a militarily strong and pro-American democracy. China’s push into Colombia comes at a time of relative absence from the United States, which has paid little attention to the continent aside from the Venezuelan crisis. A protectionist pivot by the U.S. predicated on tariffs and criticisms has left longstanding trade partners in the hemisphere considering China an increasingly attractive alternative.

Under the cusp of the COVID-19 pandemic, geoeconomic opportunities are being seized by China — and welcomed by Colombia — in the absence of U.S. reassurance. As the United States has turned inward to handle its own coronavirus crisis, it has further left nations in Latin America to secure medical and humanitarian assistance from elsewhere, particularly China. As these countries contend with the public health crisis and fallout wrought by the pandemic, the U.S. halting of funds toward the World Health Organization (WHO), which impacts the functionality of the Pan-American Health Organization, will certainly be seen negatively. Margaret Myers, director of the Asia and Latin America Program at the Inter-American Dialogue, highlights that “a number of years ago there was concern about angering the United States by engaging more extensively with China,” but, in the absence of attention from the present U.S. administration, countries such as Colombia have felt their hand forced.

In South America, CCP donations are the result of a shared effort between authorities linked to the Labor Department of the CCP’s United Front, Chinese state-owned enterprises, and part of the Chinese diaspora. China has not shied from showcasing its ongoing “mask diplomacy” and has multiplied efforts to strengthen its public image. A simple look at the Chinese diplomatic mission’s presence on social media highlights this point. From “truths” that propose an alternate origin for the virus, to the general highlighting of its diasporic charity, the recently created Twitter account of the Chinese Embassy in Colombia has taken every chance to highlight China’s contrast to the United States and its responses throughout the pandemic.

Ultimately, where many industrialized nations — and particularly the United States — may call for a decoupling from China as a consequence of COVID-19, countries in South America, and the Global South at large, may otherwise buy into Beijing’s message. If a regional rapprochement with China worries Washington, it would be wise for a shift in foreign policy that exercises reassurance and backing to some of its longstanding allies.

Lukas Mejia is a Colombian-American open-source analyst who has worked with New York University, the UN CTED, and the U.S. State Department’s Global Engagement Center. On Twitter @LukasNMejia.

Marine Ragnet is a French-American public and international affairs professional who has previously conducted research for the French Ministry of Foreign Affairs, the European Commission, and presently for a U.S. State Department-mandated platform. On Twitter @MarineRagnet.