“It’s worse, much worse, than you think,” David Wallace Wells writes in his 2019 book about climate change, The Uninhabitable Earth. After interviews with over 100 climate experts, he contends, “climate change disproportionately devastates the developing world, and will continue to do so, with India set to be hit the hardest of any country on earth.”

Wells explains the kinds of climate cascades we will see: “Sea-level rise inundation of cropland with more and more saltwater flooding, transforming agricultural areas into brackish sponges no longer able to adequately feed those living off them; flooding power plants, knocking regions offline just as electricity may be needed most; and crippling chemical and nuclear plants, which, malfunctioning, breathe out their toxic plumes.”

On Sagar Island, in the Bay of Bengal, many of these climate cascades are already playing out and are expected to worsen in the coming decades. Across the more than 100 islands constituting the Indian Sundarbans (an area with a population of 4.5 million), Sagar Island is the largest and most populated with more than 200,000 inhabitants, and growing. As the world’s largest delta region, connected to Bangladesh, Sagar has become emblematic for climate scientists and researchers as a climate change “hotspot” and a glimpse into what India’s climate future may look like.

With more than 20 percent of India’s population (about 250 million people) living within 50 kilometers (31 miles) of the sea, the country’s 7,500-kilometer-long coastline is considered the world’s most vulnerable to the impacts of climate change. Extreme temperatures, changes in rainfall, the incidence of extreme weather events, and sea-level rise are all expected to increase.

Hindu pilgrims pack dilapidated ferries running from the mainland, Kakdwip, to Sagar Island to bathe in the waters and pray at Kapil Muni temple. Photo by Nicholas Muller.

Depending on various emissions scenarios, it is projected that the sea level in the Asia-Pacific region could rise between 0.4-0.6 meters (1.3-2 feet), and temperature could see increases of up to 2.6-4.8 degrees by 2100. The multitude of climate stressors India faces is overwhelming: increasingly severe storms (cyclones), floods, heatwaves, droughts, water stress, disease, poor air quality, food insecurity, and mass displacement. According to the UN’s Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), the maximum intensity of hurricanes will increase by about 5 percent within the century. The economic cost would run into tens of trillions per year by 2100.

A Hindu pilgrim entering the sea as part of a prayer ritual. Hundreds of thousands of pilgrims come from all over India to this spot on Sagar Island each year in January. Photo by Nicholas Muller.

According to Dr. Joyashree Roy, an eminent researcher in the field of environmental economics and climate change, and among the network of scientists who shared in the 2007 Nobel Peace Prize awarded to the IPCC, “India should lead the demand for greater and accelerated collective ambition towards mitigation efforts at the global level. It is absolutely urgent for India to save a huge burden of loss and damage as it has the largest share of the global poor population exposed to all kinds of climate risks and megacities with high population densities. Putting a monetary value will not do justice to capture the enormity of the problem.”

Female Hindu pilgrims on the beach of southern Sagar Island come to bathe in the holy waters and pray at the Kapil Muni temple 700 meters away. Photo by Nicholas Muller.

Sagar Island is of great significance to Hindus. Every January, more than half a million pilgrims descend on Sagar for the Gangasagar festival as one of Hinduism’s most sacred pilgrimage sites. Pilgrims come for puja (prayer) at the Kapil Muni temple, and bathe in its southern beaches, where the Ganges collides with the Bay of Bengal. With the site only connected to the mainland by ferries, hundreds overcrowd onto decrepit barges to get there. The temple has supposedly been lost to sea at least four times.

The island is under threat: Coastal erosion is happening here faster than anywhere in the world. NASA Landsat satellite imagery shows that the sea level has risen in the Sundarbans by an average of 3 centimeters (1.2 inches) a year over the past two decades, and the area has lost almost 12 percent of its shoreline in the last four decades.

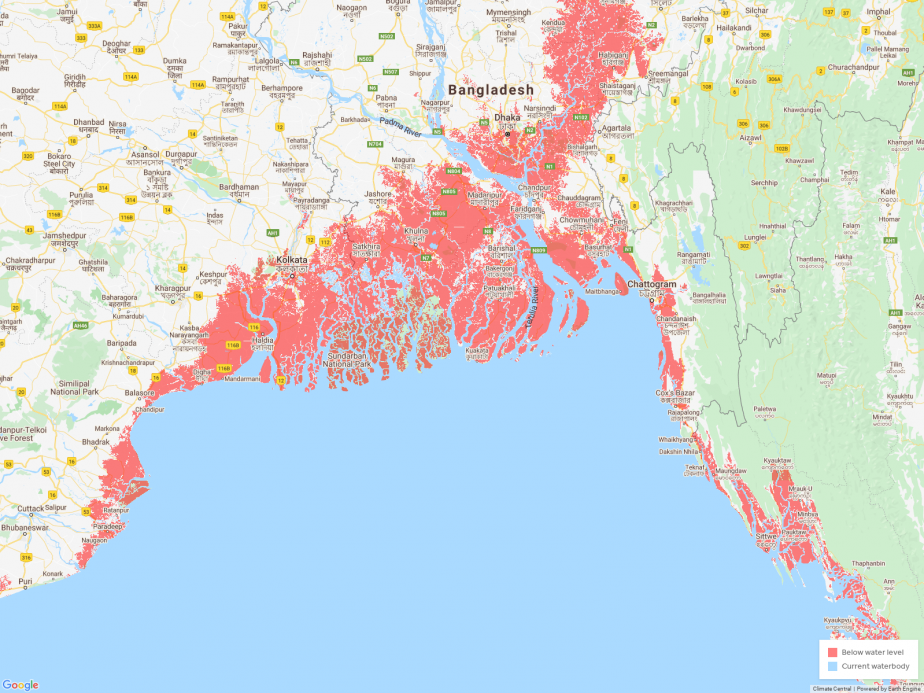

From Climate Central. The areas in red denote places that would be below the annual flood level by 2050.

According to Climate Central’s latest research, sea level rise could affect three times more people than previously calculated by 2050. This would erase Asian megacities including Bangkok, Shanghai, and Mumbai at high tide. Climate Central’s data indicates that the Sundarbans, Kolkata, and Dhaka would not be immune either. The organization’s coastal risk screening tool models land projected to be below annual flood level in 2050. Based on elevation alone, the tool does not factor in coastal defenses such as seawalls or dikes being built.

Erilokesh Dhali runs an ashram (a retreat community) for pilgrims coming to the island. A lifelong resident of Sagar, he has seen immense changes in the Sundarbans. Over the past 25 years, four islands have already disappeared: Bedford, Lohachara, Kabasgadi, and Suparibhanga. Lohachara became well-known as the first inhabited island in the world to disappear. Together, these delta inhabitants are India’s first climate refugees. Dhali has temporarily housed people displaced from neighboring islands.

Erilokesh Dhali, lifelong resident of the island, fears another major storm like cyclone Bulbul, which hit in November of 2019 in West Bengal and caused tens of thousands to flee the Sundarbans (West Bengal and Bangladesh). Some did not return. Photo by Nicholas Muller.

One of them is Bablu Paik.

Paik, born on neighboring Ghoramara Island, fled the island several years ago after he lost his home to the sea. The ever-shrinking island is now less than 5 square kilometers, with more than half of the land already underwater. Paik’s family and thousands of other displaced people were relocated to Sagar Island over the last three decades.

Bablu Paik brought his family from neighboring Ghoramara Island to Sagar Island after losing his home to the sea. He is not optimistic about the future for Sagar island either. Photo by Nicholas Muller.

Dr. Nilanjan Ghosh, director of the Observer Research Foundation in Kolkata, says, “While the intensity of extreme events has increased (despite its frequency coming down), it is further challenged by relative mean sea-level rise.”

A plot of land in Paik’s village destroyed by last November’s cyclone. Besides farming, many on Sagar Island throughout the Sundarbans rely on fish farming or aquaculture to survive. During storm surges, these tiny plots are destroyed by sea water. Photo by Nicholas Muller.

Dimming Prospects

When farming has faltered, people in the Sundarbans turn to fishing as a second source of sustenance. Lamentably, unsustainable fishing practices in the delta, such as commercial trawling, have depleted the hilsa, a key fish of high nutritional value to people all over the Bay of Bengal. The increased number of boats, in combination with continued land degradation decreases the prospects even further for fishermen. Aquaculture is also popular, but depends on farmers’ small plots being protected by embankments, which are often flooded during storms. When water rushes in from the sea, the plots are ruined.

Houses a kilometer away from the shore are still susceptible to sea water if a storm surge occurs. Salinization has seeped into the soil, which has made increasing amounts of land unfarmable. Photo by Nicholas Muller.

Last year, cyclones Fani and Bulbul battered the island and Paik’s village in the south of Sagar. Paik’s house was damaged, but many neighbors were not as lucky. Besides the harsh winds and heavy rains, residents have to live with the reality that at sea level, any storm surge can come several kilometers inland and inundate everything. Even after a storm passes, the salt water lingers and penetrates the soil, leaving it unusable sometimes for multiple seasons. Access to freshwater is increasingly difficult for those living on the island.

Two boys on Sagar Island bring back freshwater to their village from one of the few remaining water sources left on the island, which is several kilometers away. Photo by Nicholas Muller.

As sea levels rise, salinization creeps into the soil and can ruin crops for multiple seasons while devastating farmer livelihoods. Salt-resistant crops have been introduced and met with some success, but it is merely a temporary fix. The Bay of Bengal is one of the hardest-hit regions in the world from cyclones, mainly in April-May, and in October-November. Cyclone Bulbul, a category 2 storm in November 2019, affected more than 3.5 million people. In the last two decades alone, there have been 10 cyclones to hit West Bengal and neighboring Bangladesh. Cyclone Aila in 2009 displaced a million people in both countries.

Deeper into the Sundarbans, on both sides of the border, starting in April locals can get by, although perilously, in the forest, collecting honey, crab, or shrimp. None of that exists on Sagar, where resources are depleted. Unprotected communities are more vulnerable to increased food, water, and health insecurity, which will make it harder for them to adapt in the future in an already highly dense state. The state of West Bengal alone has an estimated 92 million people. These difficulties have been documented in neighboring Bangladesh, where coastal climate change has led to conflict and mass migration among shrimp farmers to its cities.

Fishermen sell their catch at dusk in the market near the Kapil Muni temple. Fish stocks have severely dwindled because of overfishing and the hilsa, one of the most important fish to Bengalis, is hard to find. Aside from farming, fishing is the main source of income for people in the Sundarbans. Photo by Nicholas Muller.

Crop failure can be so dramatic on some parts of the island that a large portion of male residents are forced to find work elsewhere: in nearby Kolkata, south India, or in Gulf countries at construction sites. Across India, crop failure has pushed thousands of debt-ridden farmers to suicide. According to a 2017 study published in the journal PNAS, over the last three decades in India, 60,000 suicides have been attributed to climate change. Dr. Tamma Carleton forecasts that as temperatures continue to rise, suicide rates will continue to increase as well.

In a Global Climate Risk Index 2020 analysis by Germanwatch, India was ranked fifth in the world for countries affected in 2018-19 by extreme weather events. Since 2004, India has experienced 11 of its 15 warmest recorded years and is “highly vulnerable to extreme heat due to low per capita income, social inequality and a heavy reliance on agriculture.”

According to the World Bank, in South Asia upwards of 800 million people will be directly affected by climate change and their living conditions will sharply diminish by 2050. According to the AQ Index, 21 out of the 30 most polluted cities in the world were in India in 2019. India was ranked fifth among the world’s most polluted countries. The economic toll for India is already enormous. It is estimated that the Indian economy is 31 percent smaller than it would have been without climate change. According to the World Bank, India’s healthcare costs and productivity losses from pollution amount to up to 8.5 percent of its GDP.

Fisherman at dusk after all day at sea on Sagar Island. Livelihoods are becoming harder and riskier for fishermen as fish stocks become increasingly depleted. This forces them out even further to sea by several kilometers. Photo by Nicholas Muller.

Coal Is King, But Fading

Although India has made significant efforts and progress to diversify its energy supply toward more renewable sources, coal remains king. According to the IEA, coal will continue to drive India’s economic growth by an estimated 4.6 percent through 2024, and the country’s demand for coal will likely grow faster than any other country globally within that period.

In the background thousands of villagers and pilgrims commute each day from the mainland to Sagar Island on old ferries. Food must be imported on the same boats, as numbers of people rise on the island and agricultural sources become more scarce. Photo by Nicholas Muller.

Even as coal use has slightly faded in 2019, CO2 emissions by coal are anticipated to grow by 1.8 percent this year, which is substantially less than half the average growth rate of the last five years. India’s emissions were expected to increase by only 1.8 percent in 2020, compared to an 8 percent jump in 2018. Power generation from renewables is forecast to expand strongly, with wind capacity doubling and solar increasing fourfold between by 2024.

Women walk off the old ferry onto Sagar Island. Photo by Nicholas Muller.

Despite progress, dozens of coal-fired power plants are still in planning throughout India. One of the most controversial is on the other side of the Sundarbans, where India has backed a large station in Bangladesh (Rampal). Many climate experts see this as counterintuitive to India’s stated climate objectives and something that could potentially lead to even more pollution in the delta.

A Crumbling Wall

For the 4.5 million who live in the Indian delta region, the mangrove forest is a crucial natural blockade against cyclones, storm surges, and tides. In 1999, during a super cyclone that struck the neighboring state of Orissa, research found that villages with wider mangroves between them and the coast experienced significantly fewer deaths than ones with narrower or no mangroves. The felling of trees is rampant throughout the delta region, although illegal, with the strong wood used to build boats and for building materials.

This unique mangrove ecosystem also is one of the last sanctuaries for thousands of plant and animal species, most famous for endangered Ganges dolphins and Royal Bengal tigers. Now that the two countries better understand the importance of mangroves as an important barrier to mitigating strong storms, India and Bangladesh have sought to harshly punish those caught illegally logging. In practice, however, the expansiveness of the delta makes enforcement difficult.

Although logging is banned, local villagers haul away logs from trees on the beach, which have served as a natural barrier to coastal erosion and flooding. Mangroves, which serve the dual purpose of carbon sequestration and protection from water surges, have also been heavily stripped bare. Photo by Nicholas Muller.

According to Ghosh of the Observer Research Foundation, “The problem also lies with the decline of sediment flow through the Ganges and its tributaries due to upstream constructions (including the Farakka barrage), which arrest the sediments in their upstream. Hence, the soil formation of the delta (the Ganges delta is formed by the sediments brought in by the Ganges and its tributaries) is largely inhibited. On the other hand, sea level rise and decline in streamflow also leads to salinity ingression (intrusion).”

Fishing boats parked inland during low tide. Photo by Nicholas Muller.

Degradation of the mangrove ecosystem has severely depleted the tree stock of the most important trees in the Sundarbans: The Sundari tree. The number of Sundari trees has decreased by 76 percent in 70 years. To survive, Sundari trees need low saline conditions, but they are under severe threat from the lack of freshwater reaching the Sundarbans and increasing amounts of salt water inundating them from the sea. Meanwhile, the roots of the mangroves secure the soil from disintegrating, literally holding the land together, but today it’s not enough.

Much of Sagar Island’s natural barriers have been severely eroded by coastal flooding and rising sea levels. This has resulted in the displacement of people to the mainland due to increasingly unusable land destroyed by the storm surges during cyclones. Photo by Nicholas Muller.

A Threat From Both Sides

According to the World Resources Insitute’s Aqueduct Water Risk Indicator for 2019, India ranks 13th for overall water stress, fourth for drought risk and has more than three times the population of the other 17 extremely highly stressed countries combined. West Bengal and the Indian Sundarbans are no exception. Reliant on the Ganges-Brahmaputra Basin, the area is labeled as at high water risk.

Mangroves also act as vital “carbon sinks,” efficiently removing CO2 through natural carbon capture. One study estimates that the Sundarbans have soaked up 45 million tons of carbon dioxide. Black carbon is likely to be responsible for a considerable part (around 30 percent, by some calculations) of the glacial retreat that has been observed across the larger Hindu Kush-Himalayan region. Glacial melt from the Himalayas has doubled since 2000 and in the last 40 years approximately 25 percent of glacial ice has been lost. Melting Himalayan glaciers and loss of snow accumulation pose a significant risk to stable and reliable water resources to major rivers such as the Ganges, Indus and Brahmaputra, which depend significantly on snow and glacial melt water. This in turn presents a freshwater risk for the Sundarbans as part of the Ganges River Basin.

Three young boys run towards the cut down mangroves on Sagar Island. Most of the trees and mangroves on the island which have protected the surrounding villages have been cut for firewood, boats, or building materials. Photo by Nicholas Muller.

More Chinese dams are also planned for the Brahmaputra basin, which could devastate the Himalayas, subsequently starving Sundarban mangroves of their last freshwater resources. By 2060, according to the Hindu Kush Himalaya Assessment, suggested that “Increasingly uncertain and irregular water supplies will impact the 1 billion people living downstream from the Himalaya mountains in South Asia.”

A Future Health Emergency

Coastal flooding, which often comes to the delta, has important health implications, too, for a future health crisis in the region. Cyclones, storm surges and flooding can become vectors for a host of water-borne illnesses, as well as dengue and malaria, both mosquito-borne. Under high emissions scenarios, climate change is expected to make the prevalence of disease, particularly water-borne illnesses even higher.

In the 19th century, cholera spread across the world from the waters of the Ganges delta, becoming a global pandemic. After Cyclone Aila in 2009, a severe cholera outbreak across the delta occurred, and has been a major concern for health officials ever since as contaminated drinking water is often the main source for such outbreaks. Increased saline water levels also increases incidence of high blood pressure and fever, as well as respiratory and skin diseases.

The World Health Organization’s 2014 risk assessment predicts climate change could cause a quarter of a million more deaths per year between 2030-2050, with tens of thousands of people dying of heat exposure, diarrhea, malaria, and malnutrition worldwide. Longer term effects of coastal flooding will include PTSD and high levels of displacement. A high incidence (30.6 percent) of post-traumatic stress disorder was reported after a cyclone that struck India in 1999. A WHO report showed that there was a “high prevalence of PTSD and major depressive symptoms have also been reported following cyclones (hurricanes) in India, Nicaragua, Sri Lanka and the USA.”

A young man riding along the seawall built to separate the island from the Bay of Bengal. Much of the island is directly at sea level making it vulnerable to coastal flooding during storm surges and from continual erosion. Photo by Nicholas Muller.

The WHO’s 2018 report on health and climate change interconnects the myriad risks which are expected to increase especially in countries like India and China. By 2050, 20.3 million people could be living in high risk cyclone zones compared to 8.3 million at present and an additional 7.6 million people could be exposed to very high salinity. In the next 50 years, over 147 million people are projected to be at risk of malaria.

International health experts warn that more “careful preparation for epidemics before the arrival of a cyclone is important to ensure a rapid response and control of outbreaks.” The rapid global spread and impact of COVID-19, even without the complications of a natural disaster, hopefully has governments paying closer attention to future outbreak preparation.

A clear example of coastal erosion happening all over the Sundarbans. Rising sea levels, stronger storms and tides, and the loss of mangroves accelerate this process. Photo by Nicholas Muller.

Mounting Climate Refugee Numbers

The World Bank says in their 2018 report, Groundswell-Preparing for Internal Climate Migration, that “without urgent global and national climate action, Sub-Saharan Africa, South Asia and Latin America could see more than 140 million people move within their countries’ borders by 2050.” The International Organization for Migration (IOM) does not put a figure forward, but forecasts the amount of environmental migrants by 2050 “will vary by a factor of 40” (between 25 million and 1 billion). The United Nations expects tens of millions of people to be displaced due to the climate crisis in the next decade alone. UN projections are even starker: 200 million climate refugees by 2050.

India has seen one the highest levels of disaster displacement globally. According to the latest figures from the Internal Displacement Monitoring Center (IDMC) (Internal Displacement Monitoring Center) India ranks at the top of the world for countries with the highest new displacements from disasters in the first half of 2019. Between 2008 and 2018, about 3.6 million people were displaced per year, mainly by monsoonal flooding.

A fisherman walks through the tide on Sagar Island to get from his fishing village to the the main town on the island. Photo by Nicholas Muller.

Politics Impeding Progress

There is an important political dimension to climate mitigation efforts in West Bengal. Political infighting between the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) and All India Trinamool Congress (TMC) has taken a toll on people in the region. Dr. Amrita Sen of Azim Premji University, wrote in Mongabay that, “The atmosphere of terror, violence and homicides that had beset election rallies of the BJP and the TMC, the two parties presently at loggerheads in the area, has only intimidated inhabitants to safeguard zones of political influence.”

Hindu monks perform a religious ritual at sunset for a family which has come to bathe in the holy waters on Sagar Island. Every January, hundreds of thousands of pilgrims come to the island. Photo by Nicholas Muller.

National and West Bengal government responses have been criticized for a lack of cohesive and comprehensive approaches to address climate stress issues. In 2017, the government of West Bengal released a second action plan on climate change and stated that they are taking climate change seriously, putting more regulations in place for the Sundarbans. Sen disagrees, writing that “[d]espite environmental regulations in place for conserving the forests of Sundarbans, the ecological crisis which manifests in the form of shrinking mangroves, remains unattended and has always taken a backseat in the agenda of the political parties.”

The newest version of the Kapil Muni temple on Sagar Island hosts millions of Hindu pilgrims a year for Makar Sankranti in January. The original site of the temple was washed away by the sea. The Indian and West Bengal governments have poured substantial investments into the temple and development of the island. Photo by Nicholas Muller.

In comments to The Hindu, Sagar Island’s development agency, GBDA, said that there is a plan for “beach protection and coastal erosion protection for 2,300 metres along the stretch of the Kapil Muni temple and the Gangasagar mela ground.” Residents of the island are not convinced that it is for them. Many island residents, who are from lower castes, are illiterate or from the Muslim minority, are resentful of being discriminated against and marginalized. Hindu nationalism is on the rise in India and violence between Hindu nationalists and Muslims has deepened since the 2014 election of Narendra Modi.

A woman brings freshwater from a water source several kilometers away as she walks over a bridge built by the local development authority. Photo by Nicholas Muller.

“In the context of climate change and Sundarbans, both central and state governments have rightly recognized that most important is coastline protection,” says Dr. Joyashree Roy. “It is good that there is growing realization that hard embankments may not be enough, and more attention and investment are going towards a nature-based solution like large scale mangrove plantation, which the IPCC reports also show as sufficiently resilient to rising temperature, and act as a cyclone protector while simultaneously providing mitigation benefits and includes citizen participation.”

On the national level and on the international stage, Indian climate policy has oscillated as New Delhi positions itself alternatingly as a developing economy and then as a country ready to take climate issues seriously. Finding an equilibrium between mitigating climate change and development necessities will be a challenge as the country will have to choose between what will drive the economy in the future and what is easily in the present: renewables versus coal. Despite hefty promises and goals, many countries, India included, as one of the top three global polluters, is not meeting targets it set during previous climate accords to seriously curtail emissions.

Nonetheless, India has put the issue of climate change higher on its foreign policy agenda, has increased the domestic awareness of the climate issue, and has seen a rise of green technologies taking off in the business sector.

Two women walk over a bridge on Sagar Island. Due to coastal flooding and degradation, much of the land previously arable has been destroyed by salinization and has turned to mud. Photo by Nicholas Muller.

Early warning dissemination systems and cyclone risk mitigation infrastructure continue to be built throughout the country, with four cyclone shelters on Sagar Island alone. To increase disaster preparedness, stronger coastal embankments, shelters, and reforestation initiatives, a coordinated response will be needed in vulnerable areas all over West Bengal. Increased cooperation with Bangladesh will also be key for the future of the region. Further investments today will minimize climate change multipliers; the economic impact of inaction will be exponentially greater in the future.

Ghosh, who views the economic outlook as bleak for the Sundarbans, has proposed the proactive adaptation approach termed “managed retreat” for the population over time as potentially the only viable option.

“In one of my estimates, if managed and strategic retreat is opted for as a mode of adaptation under global warming and climate change by 2050, the benefits will be 12.8 times that of the status quo situation,” Ghosh says.

Thousands of villagers and pilgrims commute each day from the mainland to Sagar Island on old ferries, the only current transport connection. Photo by Nicholas Muller.

As cyclones continue to intensify in this often distressed region and environmental challenges multiply, residents know another Aila or worse will wreak havoc in the near future. Tens of thousands of ill-equipped residents sitting in this perilous zone are among the least responsible for climate change emissions, but are most vulnerable to its wrath.

Bablu Paik is not optimistic about Sagar’s future. “Things won’t get better; I could lose my home again,” he says. He knows the sea is coming.