Youth in Nalaikh, Mongolia are eager to engage with their local government and participate in community-driven social initiatives, but a disconnect between democracy in theory and democracy in practice may be impeding their ability to do so. With Mongolia’s 2020 election around the corner, it is essential for leaders to note that Nalaikh’s youth view democracy in a positive light but are unclear on the role they play within it. Proactive, youth-specific outreach is required to capitalize on their enthusiasm and increase civic engagement among young Mongolians (especially if COVID-19 containment measures create barriers to election participation).

As graduate students in the Master of Public Policy and Global Affairs (MPPGA) program at the University of British Columbia in Vancouver, Canada, we spent two weeks in Ulaanbaatar center and Nalaikh District in December 2019. Nalaikh is one of the nine districts of Ulaanbaatar. With a population of just over 37,000, it is approximately 48 kilometers southeast of the capital. Working with the Governor’s Office of Nalaikh, we conducted field research to investigate how public policy can address low levels of youth civic engagement in their district.

We conducted a series of focus groups with youth in Nalaikh. These sessions included a “Democracy Mind Map” exercise, in which we divided participants into small groups and gave them a chart with “Democracy’ written in the center. We asked them to fill it in with anything that came to mind when they hear the word “democracy.” When we amalgamated the data from all groups for analysis, the results surprised us.

The majority of youth in our focus groups hesitated when asked to do this activity, and most needed some prompting to start writing. Participants were highly engaged in other activities we ran, often asking for more time or more paper — but when we turned the conversation to democracy, youth seemed less comfortable and less confident. The word cloud below shows all the terms that participants wrote down on their Mind Maps. The larger a word is in the cloud, the more often it was written.

The four translators working with us told us that during the exercise, participants seemed to be trying to recall definitions they had learned in school, rather than describing a lived experience. This inference aligns with a surprising observation from the results: the majority of terms listed are concepts or structures, but the actions of participating in a democracy are largely absent. We drew the conclusion that our focus group participants understand democracy in theory but are less clear on their role in it.

This disconnect could be one of the factors driving low levels of youth civic engagement in Nalaikh. If youth only think of democracy as a concept from a textbook, and do not relate to it personally or see evidence of it impacting their lives, then they may have little incentive to participate in local or national governance. It appears to us that for youth in Nalaikh, the link between actions (like voting or completing a survey) and outcomes (a government that better responds to their needs) is missing.

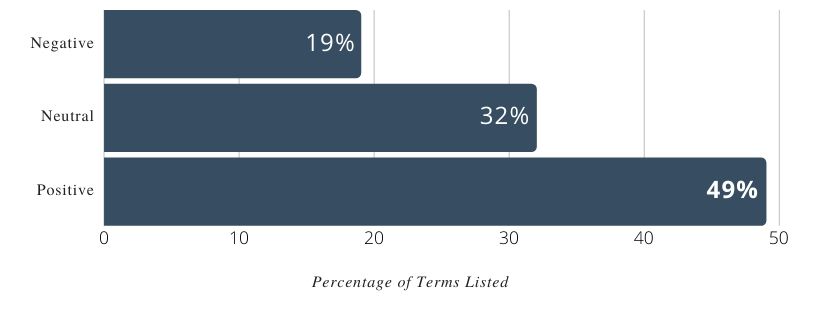

We also wanted to understand how youth feel toward democracy. We cannot gauge this definitively, because we did not ask participants to categorize their terms as “good” or “bad” during the exercise. However, we have attempted to estimate these sentiments. We assigned a value to each term based on its most common definition: positive for terms indicating an increased standard of living (i.e. “human rights”), negative for terms indicating a decreased standard of living (i.e. “alcoholism”), and neutral for descriptions of things (i.e. “law”) The results are shown in the chart below.

These estimates must be interpreted with caution, but the results do show a telling pattern nonetheless: Many of the things youth associate with democracy are neutral descriptors, but where value judgments are clear, positive associations with democracy outweigh negative ones. Despite the prominent protests against corruption scandals in Mongolia’s democracy in recent years, youth in Nalaikh do believe in democracy as a positive force. This reinforces our conclusion about civic engagement: Low engagement is not driven by opposition or negativity on the part of youth, but a lack of information about how to participate and why it’s important to do so.

There are some caveats to our findings: Our study focused on youth in Nalaikh, specifically, and was constrained by a two-week timeframe for fieldwork. Nonetheless, our data tell an interesting story that is relevant to discussion of democracy and Mongolia’s youth.

As the 2020 election approaches, Mongolian leaders should strive to involve and engage youth in the process. This begins with re-examining any perceptions of youth as apathetic or disengaged. All of the youth that we interacted with in Mongolia were bright, insightful, and passionate, and these impressions are backed up by the data we collected. Governments at all levels have an opportunity to harness this enthusiasm and foster civic engagement in the next generation of its citizens and leaders.

A high level of youth civic engagement is important for any country. Civic engagement is widely considered to be a marker of human development. Youth, in turn, are key actors in an engaged citizenry. An excerpt from the Handbook of Research on Civic Engagement in Youth puts it best: youth citizenship, in the form of “values, attitudes, knowledge, identities, and practices,” has “a direct impact on human and social capital and [creates] the political conditions within which socioeconomic development is possible.” Clearly, the stakes are high. Youth themselves also have a vested interest in the democratic process, as they will eventually inherit the results of political decisions made today.

At this critical juncture, it is essential to capitalize on the positive perceptions of democracy that Mongolian youth hold, and fill in any gaps in their understanding of themselves as democratic participants. There is consensus across various fields of research, from political science to psychology, that direct application and learning through experience are essential to building a robust sense of political efficacy in youth. We believe that if governments provide engagement opportunities catered directly to youth, Mongolia can close the gap between theory and practice and increase youth civic engagement resulting in a more robust democracy.

Claire Casher, Samantha Coronel, Rasmus Dilling-Hansen, and Cassandra Jeffery are students in the Master of Public Policy and Global Affairs program at the University of British Columbia