Australian barley exports to China worth AU$1.4 billion (US$960 million) were shaken in October 2018 when China opened an anti-dumping investigation. The trade came to a grinding halt in May 2020 when China imposed tariffs totaling 80.5 percent.

The case has been widely reported as economic coercion (against Australia’s call for an inquiry into COVID-19), retaliation (for Australian anti-dumping measures against China), and a “trap” by China (to shore up steel exports).

However a new research report argues that these factors are really just triggers for a measure that China wanted to take anyway. In the case of the barley tariffs, the underlying driver is food security. High Australian barley exports over the 2010s became a serious threat to China’s food self-sufficiency and import diversification policies, which it arrested through a dubious anti-dumping case. In other words, the barley tariffs are a classic case of protectionism.

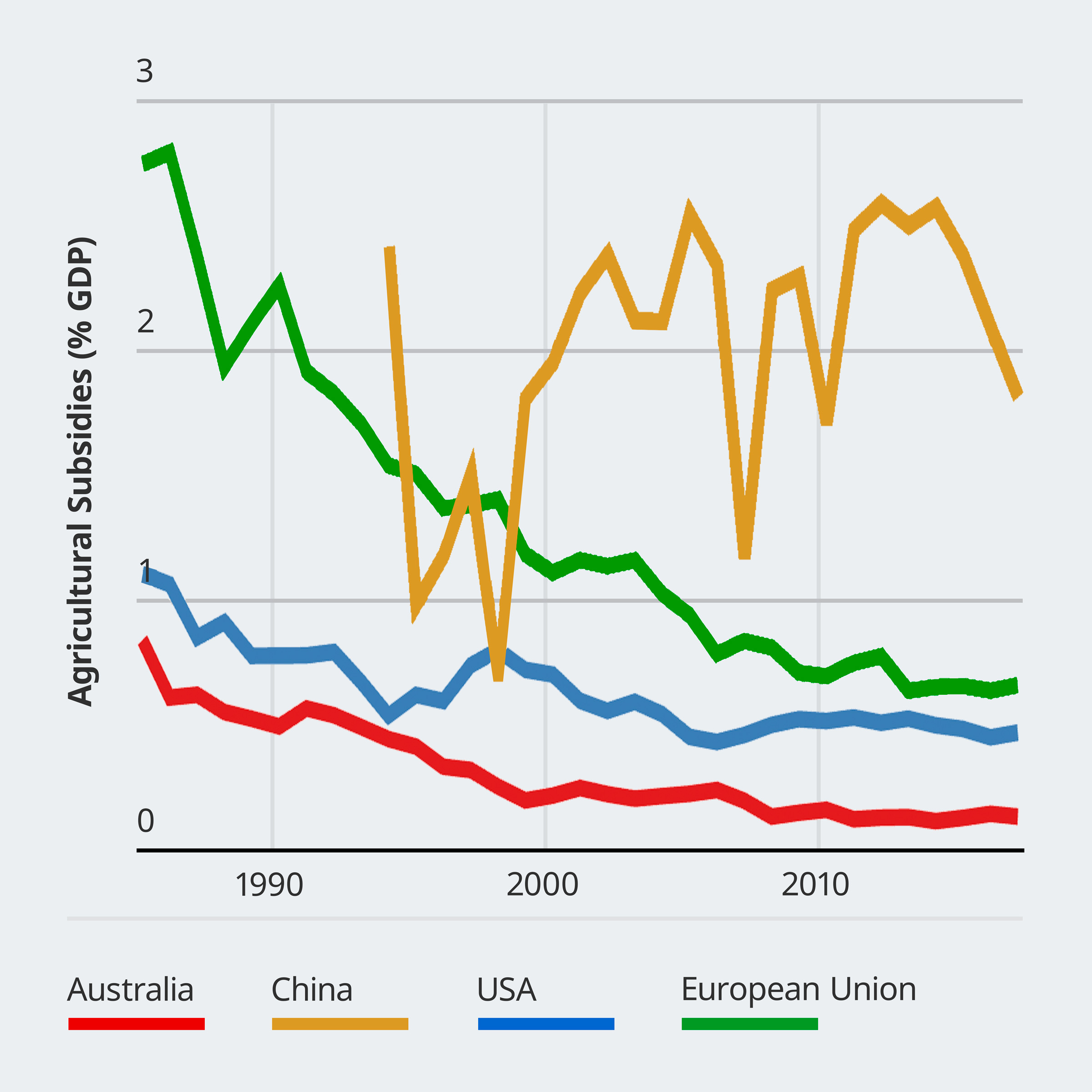

Accession to the WTO has reduced quotas and tariffs on agricultural imports but, with a history of conflict and famine, China remains preoccupied with food security. This was heightened in the global food crisis of 2008, when Chinese policymakers were convinced that the world had entered into a new era of food shortages and inflation. China now has the highest and most volatile levels of agricultural protection in the world, compared to other economies where levels are steadily declining (Figure 1). Australia has the lowest levels in the OECD.

Figure 1. Total support to the farm sector in China, the EU, the U.S., and Australia, as a percent of GDP. Total support to the farm sector includes support to individual farmers, support to the sector collectively, and consumer subsidies. Source: OECD.

In the 2010s, Chinese agricultural subsidies were directed mainly to production and price support for rice, wheat, and corn. By 2015 China had 250 million tonnes of corn in storage – half the worlds’ reserves – bought at up to double world prices and taking years to draw down. The differentials with world markets didn’t increase corn imports because they are controlled by tariff rate quotas (designed partly to reduce reliance on U.S. corn). But it did lead to massive imports of corn substitutes not protected by quotas used for livestock feed and brewing – including barley.

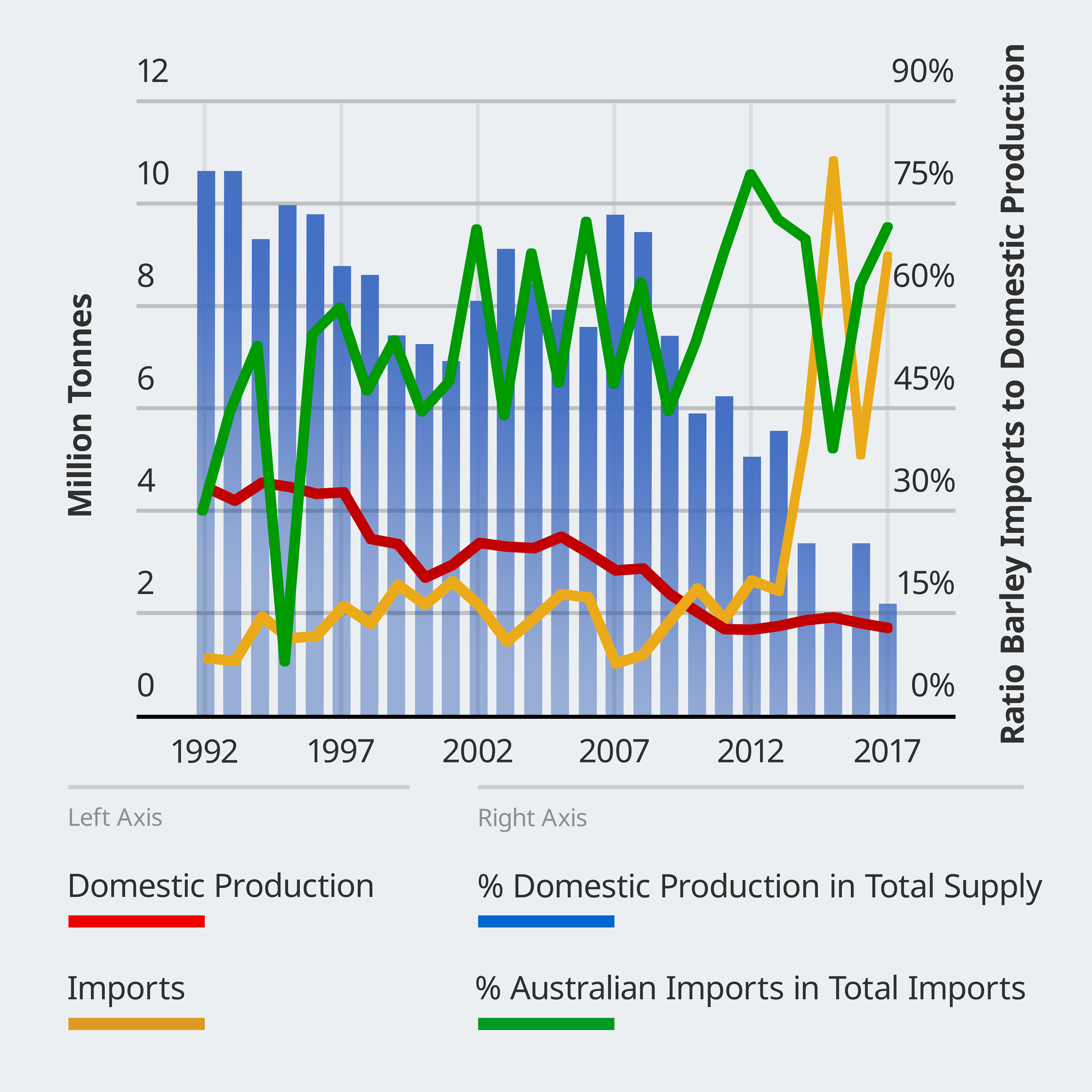

Chinese barley imports surged from 2013-18, while domestic production continued a long-term decline. The combination meant that domestic production accounted for an average of just 20 percent of total barley supply between 2014 and 2018 (Figure 2). This is an anathema to China’s food security and self-sufficiency policy. On top of that, Australia accounted for a large proportion of total barley imports – up to 80 percent in some years – which also contravenes Chinese policy to diversify import sources and reduce exposure to “unsecure” or “unstable” sources. There are parallels with corn and soy from the United States.

In the absence of quotas to control barley imports and sources, China turned to anti-dumping tariffs. The case bought by the China Chamber of International Commerce and the Ministry of Commerce (MOFCOM) is outlined in documents on the investigation and the ruling.

MOFCOM argued that Australian exporters sold barley to Chinese importers at below the cost of production. Among the inconsistencies in the claim is that the price of Australian barley sold to China – Australia’s largest market – was compared with the much higher price of barley sold to Egypt, which ranks 23rd out of 27 export markets for Australian barley. That was used to set the anti-dumping tariff of 73.6 percent. UNComtrade data shows that if prices from the second biggest market (Japan), were used as a comparison, the difference would be just 5 percent (or 7 percent for the world average, excluding China). The differences can be explained by varying volumes and grades of barley. China ignored extensive price data submitted by the Australian side.

China also claimed that the dumping caused damage to its domestic industry between 2014 and 2018, citing declines in land planted to barley, production, and the (already negative) profits of barley farmers. Importantly, most barley is produced in remote and poorer parts of China. However as shown in Figure 2 above, Chinese barley production has been in decline for decades. Even if more recent declines are related to imports, the uncompetitiveness of small-holder barley production in China compared with large-scale production in Australia does not constitute dumping. China rejected claims that domestic corn and wheat subsidies contributed to the decline of barley production.

The documents don’t specify the mechanisms by which Australia may have dumped the grain to incur a 6.9 percent anti-subsidy tariff. Conceivable subsidies, including drought relief and R&D, are green box items in WTO, and irrigation would also comply if for water-saving purposes. In any case, barley is virtually all dryland in Australia.

The China Alcohol Association made a submission to the investigation arguing that the anti-dumping measures would reduce the industry’s access to high-quality malting barley and increase the price of corn. Unlike in some other trade decisions (e.g. wool), industry interests were over-ridden by powerful agricultural and strategic interests, represented by the Ministry of Agriculture and probably adjudicated by the State Council. The final findings were that domestic barley production and logistics could be developed to fill the import gap and that the anti-dumping measures would protect farmers, national economic security, agricultural security and the healthy development of China’s barley industry.

Market and policy trends may also have contributed to China’s decision to impose the trade barriers. The Chinese beer industry is over-supplied by low-quality “water” beer and consumption is declining. Demand for feed grains declined dramatically in 2019 due to African Swine Fever, which led to a cull of half of China’s 450 million pigs. And of course the opening of the investigation coincided with the deteriorating China-Australia bilateral relationship in 2018 and the ruling coincided with Australia’s announcement of its demand for inquiry into COVID-19 in 2020.

The broader lesson from the barley case is that Australian agriculture faces significant and rising risks through high trade exposure to China. Trends in Chinese domestic agricultural policy, the bilateral relationship, and the international trading system suggest that disruptions will continue or even escalate in one form or another. Australian industry and government agencies have a strong stake in understanding and responding to the risks in a proactive and proportionate way. A good start would be to challenge China’s anti-dumping case in the WTO to uphold rules-based trade. This risks escalation, but the risks are manageable for most Australian agricultural industries.

Scott Waldron is a Senior Research Fellow at The University of Queensland’s School of Agriculture and Food Sciences.