On April 15, 2020, to ease the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic, the G-20 countries pledged to suspend debt service on all official bilateral credits due between May 1 and December 31, 2020, in low-income countries. As part of the effort to support the Debt Service Suspension Initiative (DSSI), the World Bank recently published the specific debt statistics of 72 low-income countries. This is a gold mine of data.

For decades, researchers have been frustrated by the lack of comprehensive, high-quality data regarding China’s lending overseas and to what extent the debt problems in poor countries are caused by China. Both the borrowers and China have been reluctant to bring more transparency to this matter. The World Bank regularly publishes debt statistics on most countries without providing a breakdown of the lenders. If borrowers agree, the IMF sometimes gives a lender breakdown in their Article IV summaries or Debt Sustainability Analyses, but the irregularity of reporting made it difficult if not impossible to track this systematically. Institutes like the China Africa Research Initiative (CARI) and AidData put armies of researchers to work, painstakingly collecting information about Chinese loans from a wide range of public sources. But those numbers show us only China’s loan commitments, and it is difficult to know how much of those commitments have been actually disbursed and repaid.

This new World Bank dataset is a great leap forward in transparency. It gives a detailed breakdown of stocks for public and publicly guaranteed debt in 72 low-income countries between 2014 and 2018, and projects debt service between 2020 and 2024. That is to say, we now know how much debt these governments have, and how much exactly they owe to Chinese official lenders.

We at CARI analyzed this data and this is what we found.

China Is a Big Lender

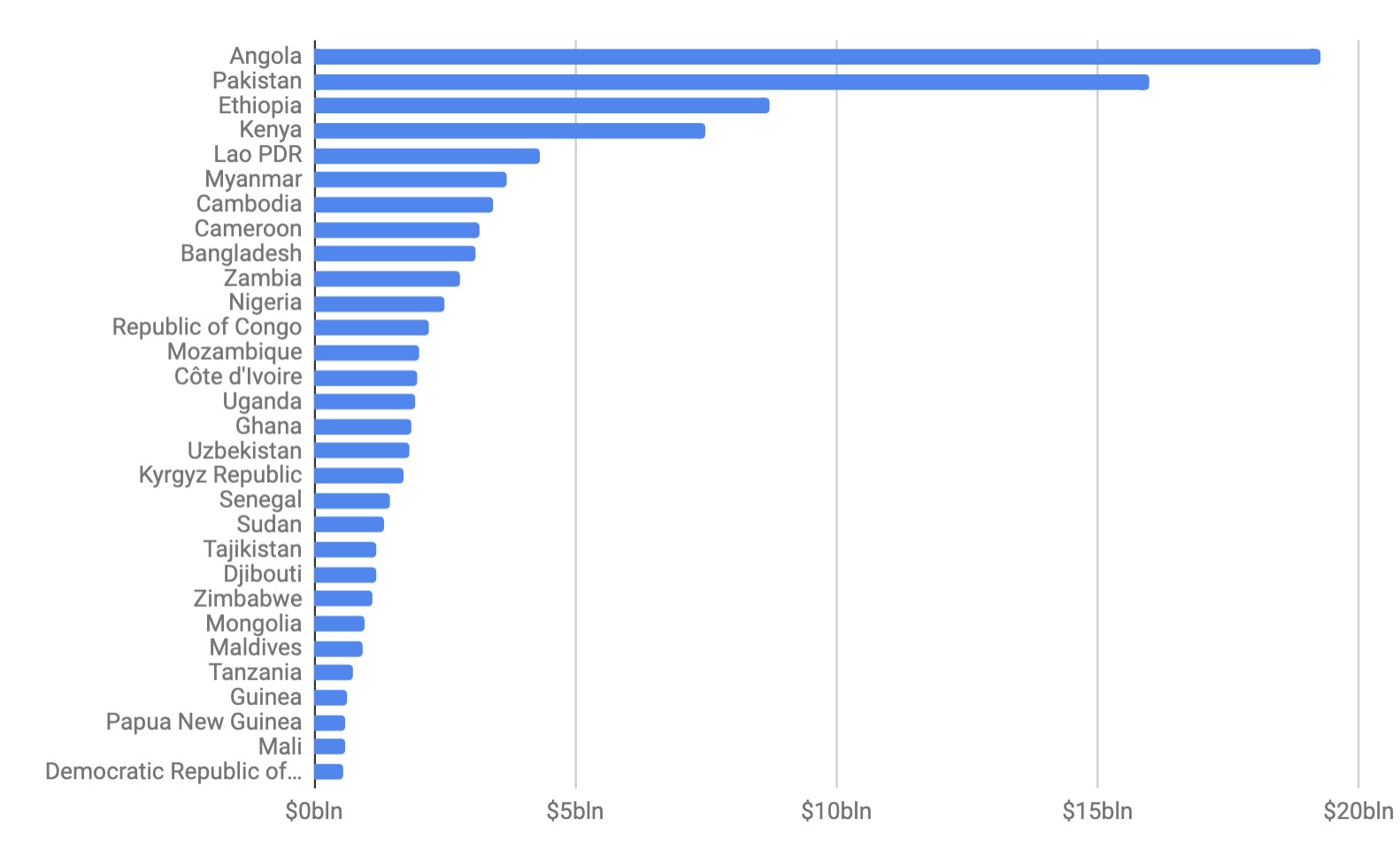

As of 2018, the 72 low-income countries covered in the dataset owed Chinese creditors $104 billion out of a total disbursed and outstanding debt of $514 billion. $64 billion of this Chinese debt, or 62 percent, was disbursed in Africa. However, overall China made up only 20 percent of the 72 countries’ total public external debt. In Africa, that proportion is 22 percent.

For the 72 low-income countries, a total of $44 billion of debt service is due in 2020, of which 29 percent would have gone to China. In Africa that amount is the same. Our Africa loan commitment data show a peak in Chinese lending in 2013 (aside from Angola). Since Chinese loans generally have grace periods of five to seven years, these figures suggest that countries are now facing significant principal repayments.

For 51 of the 72 low-income countries, and for 32 of the 40 African countries, China is the biggest bilateral official lender. In seven countries, Japan is the biggest bilateral lender; in six countries it is Saudi Arabia. The United States is a bigger official lender than China in only one country: Somalia.

Ten countries owed more to bondholders than to China. They are Côte d’Ivoire, Grenada, Ghana, Honduras, Mongolia, Nigeria, Rwanda, Senegal, St. Lucia and Zambia.

Chinese lending reached every one of the 72 countries except Afghanistan, Bhutan, Kosovo Moldova, and Timor-Leste. Of those, China does not have official diplomatic relations with Bhutan or Kosovo.

Angola owed China $19 billion and Pakistan owed $16 billion. Together, these two accounted for 34 percent of the Chinese debt for all of the 72 low-income countries. Half of all the debt service due to China this year — $6.5 billion — is owed by just these two countries.

China vs. the World Bank

In terms of outstanding debt, the World Bank is still the biggest lender for these low-income countries ($106 billion), but China is coming close ($104 billion). In sub-Saharan Africa, China ($64 billion) has outspent the World Bank ($62 billion) as the biggest lender to Africa’s poor countries. However, if Angola is removed from the data, the World Bank remains the largest creditor for low-income countries in Africa ($45 billion by China vs $61 billion by the World Bank).

Given the size of World Bank lending, it is understandable why China’s minister of finance has pointedly urged the World Bank to join in the debt moratorium. The World Bank Group (WBG) “should lead by example … If WBG fails to participate in collective actions for suspending debt service payments, its role as a global leader will be seriously weakened, and the effectiveness of the initiative will be undermined,” Minister Kun Liu said in April. David Malpass, president of the World Bank, rejected World Bank participation, arguing, “This would be harmful to the world’s poorest countries. MDBs [multilateral development banks] depend on financial markets, and instability in the payment stream would have a negative impact on the flows to client countries.”

China’s Role in Debt Problems

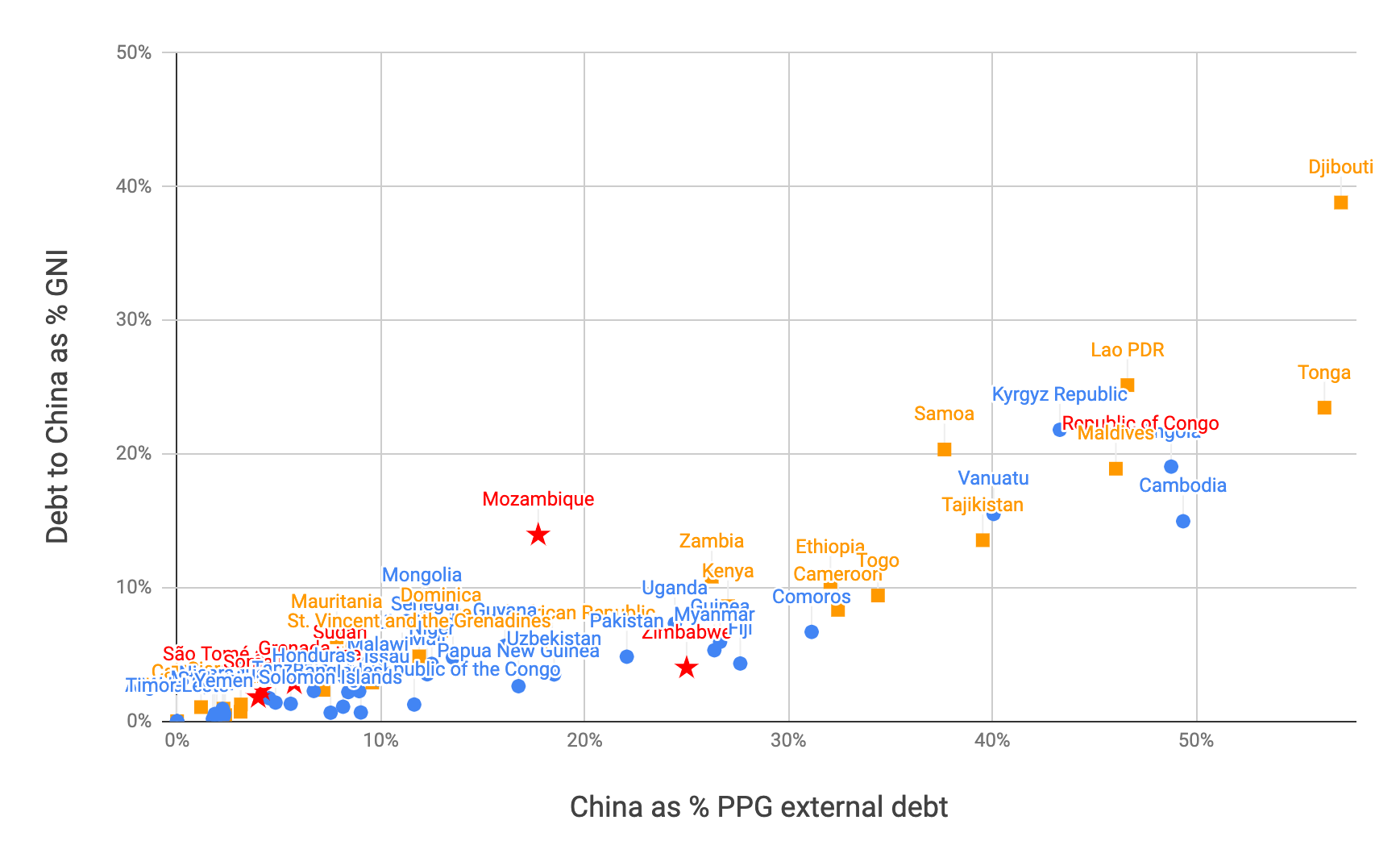

Among the 72 low-income countries, 29 are ranked by the World Bank as already in external debt distress (seven countries, marked hereafter with **), or at high risk of distress (22 countries, marked with *). China holds less than 15 percent of the debt stock in more than half of these 29 countries. That is to say, their debt problems are largely caused by lenders other than China.

In another five countries at high risk or already in debt distress, Chinese lending is between 15 and 30 percent of overall lending: Central African Republic* (18 percent), Kenya* (27 percent), Mozambique** (18 percent), Zimbabwe**(25 percent), and Zambia* (26 percent).

However, in nine countries that are at high risk, or already in debt distress, Chinese lending is an important part of the problem, making up more than 30 percent of their public external debt. These nine are Djibouti* (57 percent), Tonga* (56 percent), Laos* (47 percent), the Maldives* (46 percent), the Republic of Congo** (45 percent), Tajikistan* (40 percent), Samoa* (38 percent), Cameroon* (32 percent), and Ethiopia* (32 percent). Four of these countries are in Africa.

A scatterplot of the share of Chinese lending as a share of GNI and percent of overall debt for the 72 low-income countries. A star marks countries in debt distress; a square marks countries at high risk of debt distress. Figure by CARI.

Official and Non-official Chinese Lending

The World Bank data shows that 94 percent of the poor countries’ public and publicly guaranteed Chinese debt is from Chinese “official” lenders. In Africa, the number is 93 percent. There is no globally recognized definition of “official creditors.” The World Bank numbers were collected by its Debtor Reporting System, which uses definitions in its 2000 Debtor Reporting Manual. Here, official bilateral creditors include “central banks (but not government-owned commercial banks), and public enterprises (notably, governmental export financing institutions, development banks, and the like).” It appears that loans from China Exim Bank would be covered by the G-20 pledge, and it seems that loans from China Development Bank should also be covered, since it is a development bank. However, China might contend that CDB is a government-owned commercial bank, since it only provides commercial loans.

Our data on loan commitments for the entire continent of Africa show that for those loans with the financier identified, 56 percent are signed by China Exim Bank. China Development Bank signed 24 percent. Non-official lender the Industrial and Commercial Bank of China signed 5 percent, and Chinese companies’ suppliers credits were 7 percent. China Development Bank is mostly active in Angola, Egypt, South Africa, Ghana, and Kenya, not all of which are covered by the DSSI.

On June 17, Chinese president Xi Jinping gave a speech at a COVID-19 event in which he said: “We encourage Chinese financial institutions to respond to the G-20’s Debt Service Suspension Initiative (DSSI) and to hold friendly consultations with African countries according to market principles to work out arrangements for commercial loans with sovereign guarantees.” This is a positive sign because “encouragement” from China’s top leader will be taken seriously by Chinese banks.

However, this still leaves open which financial institutions are getting this encouragement. It’s possible that the dividing line on whether Chinese loans are considered “official bilateral credits” in Beijing is whether there is a government-to-government agreement. For example, the original $3 billion loan facility Ghana signed with China Development Bank was signed by Ghana’s Ministry of Finance and Economic Planning, but not by a Chinese government ministry. On the other hand, concessional foreign aid loans issued by China Exim Bank are government-to-government, and require an inter-governmental Framework Agreement before a separate loan agreement is signed. In Angola, China Exim Bank’s largest borrower in Africa, lines of credit from China Exim Bank are also preceded by a framework agreement signed by the Chinese Ministry of Commerce and the Angolan Ministry of Finance.

Loan Commitments and Disbursements

For the 40 African low-income countries listed, CARI was able to identify a total of $135 billion of Chinese loan commitments between 2000 to 2018. Their outstanding debt to China in 2018 is about 48 percent of that commitment. A big part of the gap we believe is due to repayments and loans not yet disbursed. In Nigeria, for example, our analysis showed that signed loan commitments between 2000 and 2017 came to $5.3 billion, but only $2.5 billion had been disbursed by that date.

Conclusion

Only countries that have no arrears to the World Bank or the IMF are eligible for the DSSI (this would eliminate countries like Zimbabwe, Eritrea, and Sudan). In the past, China has provided debt write-offs for countries that have not qualified for HIPC, the “heavily indebted poor countries” grouping, and it is also possible that China will decide to apply the moratorium more broadly.

We are now in a new era where Chinese lenders are the big bilateral creditors. A non-OECD member that does not publish details of its loan commitments creates new difficulties for the kind of trust that needs to evolve for collective action on debt reduction. Yet our latest study of Chinese debt relief showed that China has already provided loan restructuring in a number of debt burdened low income countries in Africa. Joining the G-20 moratorium is a very positive step and should be welcomed. The World Bank’s decision to publish data on all creditors provides the transparency that the markets and creditors need in order to manage debt distress in the era of COVID-19.

This piece was updated on June 25 to include additional World Bank data.

Yufan Huang is a Research Assistant at the China Africa Research Initiative at the Johns Hopkins School of Advanced International Studies (SAIS).

Deborah Brautigam is Bernard L. Schwartz Professor of International Political Economy and Director of the SAIS China Africa Research Initiative.