The COVID-19 pandemic has added to the woes of the Indian economy, which was already reeling from a pre-lockdown slump. With the exception of the rice milling sector, a survey conducted by the United Nations Industrial Development Organization (UNIDO) to assess the impact of COVID-19 on India’s economy noted that manufacturing in India has come to a complete standstill. Economic stagnation was already beginning to reflect in data released by India’s Central Statistics Office, which indicated that gross domestic product rose only by 3.1 percent in the fourth quarter of financial year 2020 (January to March) — the lowest quarterly GDP growth since the fourth quarter of financial year 2009.

To spur economic growth in India, Prime Minister Narendra Modi recently announced a $265 billion stimulus package, called the “Atmanirbhar Bharat Abhiyan” (Self-Reliant India Scheme). This scheme amounts to roughly 10 percent of India’s GDP. In his address, Modi said: “India’s self-reliance will be based on five pillars — economy, infrastructure, technology-driven system, vibrant demography and demand.” Indian Commerce and Industry Minister Piyush Goyal later argued that India did not want to be “dependent or at least not overly dependent on the rest of the world.” Instead, it was confident of its ability to “produce quality products…in a cost-competitive manner, that [it could] compete with anybody in the world…even given some of disadvantages that [India] faces.” New Delhi has declared its intention to prioritize cottage and home industries, small and medium enterprises (SMEs) and other ancillary industries. Further, it has committed to enhance manufacturing in the PV cell sector, and identified five “Champion Sectors”— pharmaceuticals, textiles, gems and jewelry, renewable energy, and leather—to boost production.

The effects of this reorientation toward domestic manufacturing are already visible in India’s international trade policy, where it seems determined to protect its domestic policy space. For instance, at the Special Virtual Meeting of the General Council of the World Trade Organization (WTO) on COVID-19 Trade-Related Measures, India’s Ambassador and Permanent Representative J.S. Deepak emphatically rejected demands for permanent tariff liberalization and implementing binding commitments on e-commerce. This was in response to calls by some countries to permanently eliminate tariffs on an extensive list of “essential goods.”

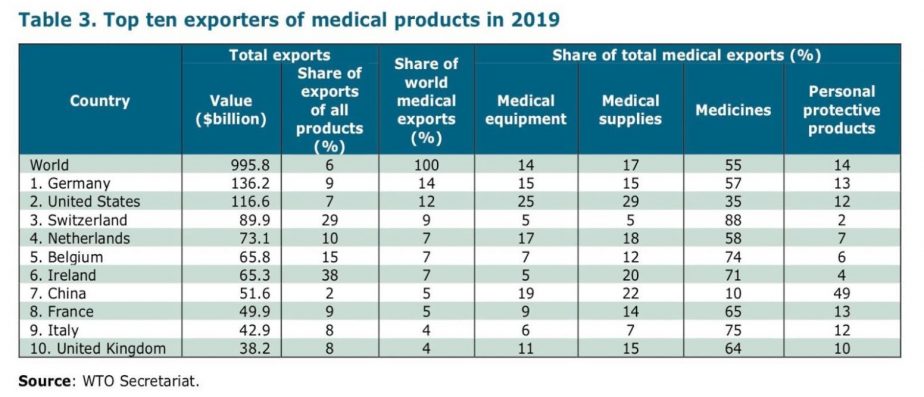

Tariffs are likely to play a key role in Modi’s agenda with respect to providing a fillip to India’s manufacturing sector. For example, while India is a major exporter of the world’s APIs (Active Pharmaceutical Ingredients) — which are used in the making of medicines — India does not account for a significant share of medicines exported in their final form. With the singular exception of China, the market of medical products in their final form, which includes medicines, medical supplies, medical equipment and technology, and personal protective products, is dominated largely by developed countries. The top 10 exporters of medical products exercise a clear monopoly and account for almost three-quarters of world exports reflecting a highly concentrated distribution. The table below shows the share of world exports by the top 10 exporting countries:

Currently, India applies a 10 percent tariff on imported medicines and a 12 percent tariff on personal protective products. Succumbing to the calls of permanent tariff liberalization would have the effect of flooding Indian markets with medical goods from developed countries. Not only would this hinder long-term growth of the domestic industry and prevent local manufacturers from being competitive, it would also create dependencies on developed countries for access to essential products. Tariffs, therefore, remain an important policy tool for India to aid the growth of the domestic industry and stabilize prices as the country seeks to enhance manufacturing capabilities.

Second, on the e-commerce front — which is defined as the “production, distribution, marketing, sale or delivery of goods and services by electronic means” — India has censured negotiations at the WTO on binding disciplines that could limit India’s ability to regulate in this space, especially with regard to data localization. Data localization is defined as “policies [that] involve restrictions on the ability of firms to transmit data on domestic users to foreign countries.”

A technology-driven “Atmanirbhar Bharat” relies heavily on digitizing India, with an emphasis on health and education technologies. As a part of this scheme, the government aims to implement the National Digital Health Blueprint under the National Digital Health Mission. India’s increased use of digital health technology is captured in a recent report titled “Digital Health in the Aftermath of COVID-19” by Invest India. The report highlights the use of digital health technologies in India, including the use of the Aarogya Setu app and the e-Sanjeevani app, and the development of digital frameworks such as National Heath Stack (NHS) framework and the National eHealth Authority (NeHA) framework. It further notes the importance of big data in relation to “citizens’ movement, disease transmission patterns and health monitoring, which could be used to aid prevention measures.”

Digitization, especially in sensitive sectors such as health, raises concerns regarding the safety and security of data. Health data is particularly sensitive as it allows governments and corporations to access an individual’s private sphere. It thus becomes necessary for countries to limit offshore data storage and implement strong data localization laws. Committing to disciplines at the WTO that require the free flow of data would limit India’s ability to regulate its citizens’ data. The existing digital divide and asymmetry in digital technology would result in a unilateral flow of data from India to the advanced economies and make such countries the repositories of global data. In the absence of data localization requirements, infant digital platforms and industries would be denied support, resulting in an increase in existing inequalities. Data localization requirements would thus play an increasingly important role in securing India’s technology-driven economy and claiming an equal stake in the benefits of a digitized world.

Much like the rest of the world, COVID-19 seems to have ushered a greater emphasis on domestic capacity building in Modi’s India. However, its economic ambition to become a global manufacturing hub sits awkwardly with protectionist trade practices and supplementary emphasis on data localization described here. The Indian government looks to attract foreign investors by leveraging the availability of cheap labor and access to domestic and international markets, while simultaneously trying to protect nascent domestic industries from crushing international competition. Thus, Modi’s ambition to achieve a self-reliant but globalized India rests on his administration’s ability to dexterously navigate this seemingly contradictory terrain.

Ameya Pratap Singh is DPhil student in area studies (South Asia) at the University of Oxford.

Urvi Tembey is an international trade and investment lawyer.