A new session of South Korea’s National Assembly officially opened last week following a long delay after April’s election. President Moon Jae-in’s Democratic Party now holds a clear majority and has a relatively free hand to pursue items on its agenda.

The day after the opening ceremony was Constitution Day, and the assembly speaker from the Democratic Party took the opportunity to raise the possibility of constitutional reform. An attempt at constitutional reform had been made – and thwarted – in the 2017-18 session. Now that the party has a majority, it can propose an amendment without needing the support of other parties.

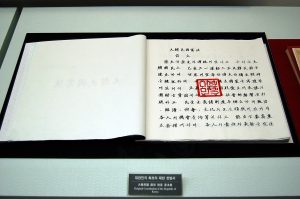

The argument for constitutional revision stems, in part, from the long period that has passed since the last amendments were made. South Korea’s constitution has stayed unrevised since 1988. That moment marked the single largest step toward democracy in the country’s political transformation. Prominent dissidents had their political rights restored and opposition figures were given a fairer chance to vie for power. In the three decades since the promulgation of the amended constitution in 1988, a feeling has grown that the constitution needs to be updated for a society that is far more democratic and facing new challenges.

Constitutional reform proposals center on the presidency. South Korea’s president serves a single five-year term. The Democratic Party is likely to propose a shift to a two-term presidency. The grounds for this proposal, which has been discussed since the 1990s, lie in the view that presidents become ineffective in the final two years as bureaucracies respond less enthusiastically to orders from above.

Another possible proposal would give expanded powers to the prime minister, who would have discretion over, for example, foreign affairs. The motivation for this proposal is, in ways, opposite to the first. It stems from a concern that the office of the president is too powerful. Sharing authority with a prime minister would address that concern, while also incorporating inter-party negotiation into the policymaking process.

Despite the favorable conditions in the National Assembly, constitutional revision is difficult. There have been multiple prior attempts. Most recently, in 2017-18, Moon’s Democratic Party held fewer seats but there was a broader commitment to constitutional reform. The Candlelight Movement of 2016, which culminated in the impeachment and dismissal of then-President Park Geun-hye, generated wide support for revising the constitution. And yet the moment passed.

The obstacle to constitutional reform relates as much to symbolic politics as to legal or procedural matters. South Korea lacks a precedent for legitimate constitutional amendment. Self-serving constitutional revisions occurred regularly under authoritarian rule. Those episodes made constitutional reform a suspect activity. What would a legitimate reform process under democratic conditions look like? In South Korea, we do not have an answer to that question. The president and the Democratic Party can make a strong argument, but the forces opposing revision – and their support in news media – will challenge it at every turn.

The next six months might be the perfect moment for updating South Korea’s formal order. The timing is good not only because of Moon’s support in the legislature but because of the strong legitimacy the Democratic Party has built through political events of the past few years. The historic Candlelight Movement was followed in 2019 by mobilization demanding reform of the prosecution, another element of the old order widely seen as in need of updating for a democratic society. April’s election result underscored popular support for the project of reforming the state. A constitutional revision in the same spirit could be an ideal next step in this project.

If, however, the challenges to constitutional reform prove too great – or if the Democratic Party opts not to pursue it – reformers need not feel too pessimistic.

The focus on constitutional revision might overstate the constitution’s significance. Constitutions do different things depending on the context. The South Korean Constitution, first written in 1948, was meant from the beginning to signal liberal commitments in a context of division where security concerns would trump those commitments. The condition of division meant that constitutional guarantees were circumscribed – a point that all major political figures understood perfectly well. The constitution promised many freedoms, but security laws drew boundaries around those freedoms. In the name of preventing alleged threats from Pyongyang, regimes put limits on political rights. As leading Korean intellectuals have argued, these conditions made the constitution a more superficial part of the public order.

In addition, South Korea has changed constitutionally without constitutional revision. A constitutionally-promised Constitutional Court was established after 1988 and has become an important body. The National Security Law has been used less frequently for domestic political purposes, enabling promises in the constitution to matter more. The Candlelight Movement also brought citizens onto the streets to defend the constitution; it was arguably a moment when ordinary people demonstrated a commitment to the constitution. All these developments are of constitutional significance, though none involved constitutional amendment.

For administrations seeking to address the challenges of the present and future, state reforms are needed and these may not require constitutional revision. The South Korean state is one that, for historic reasons, excels in activities such as infrastructure development. Moon and many in his party strive to improve the state’s ability to address problems of distribution, diversity, health, and the environment. Implementing reforms to make the state more responsive in these areas is a major task. Moving to a two-term presidency could be a major help in this effort. At the same time, if constitutional revision proves too difficult, other types of reform could also be effective.

When constitutional revision efforts stalled most recently, attention turned to other crucial areas, including election reform and prosecution reform. After major political and public battles, the election law was successfully revised; prosecution reform is currently underway. These developments indicate that movement toward profound change can occur.

The challenge of constitutional reform is big, but that does not preclude major change in the public order. Moon’s legislative majority can prove useful in enacting shifts that make the state more responsive to the demands and aspirations of Koreans in the 21st century.

Erik Mobrand is associate professor in the Graduate School of International Studies at Seoul National University. He is the author of “Top-Down Democracy in South Korea” (University of Washington Press, 2019).