Chinese President Xi Jinping has signed a new national security law for Hong Kong, which covers four categories of offenses, including “secession, subversion, terrorist activities, and collusion with a foreign country or external elements to endanger national security.” The new legislation aims to “stop and punish activities endangering national security” and “oppose[s] the interference … by any foreign or external forces.” It allows the Communist government to establish security agencies that can openly operate in the city. As the move has placed the former British colony firmly under Beijing’s control, observers worry that it will further curtail the political freedom and the rule of law that the “one, country, two systems” unification plan has promised. This development has wider implications that go beyond Hong Kong, as the same plan has been repeatedly pitched to Taiwan by Chinese leaders who view the island as a renegade province.

At the end of the Chinese Civil War in 1949, the two sides of the Taiwan Strait were divided and embarked on different paths. Since then, Taiwan has transformed itself from a one-party authoritarian regime to a full-fledged democracy while China has continued on its way of communism. Chinese leaders, nevertheless, have always considered “Taiwan’s return to the motherland” as an important step toward national rejuvenation. To entice Taipei into unification talks, Beijing has offered the “one country, two systems” framework. Essentially, the plan prescribes that the island be unified with China, and Beijing will be the central government, while Taiwan becomes a local special administrative region (hence the “one country”). After the proposed unification, the Chinese mainland would continue the practices of communism while Taiwan retains its capitalist system and enjoys a high degree of autonomy (hence the “two systems”). In attempting to force Taipei to accept its unification proposal, Beijing has isolated Taiwan internationally, backing up its claim over the island with the threat of military force.

Since the “one country, two systems” idea was raised in the Taiwan context in 1979, China’s unification plan was first implemented in Hong Kong and in Macau after their handovers to China in 1997 and in 1999, respectively. The implementation of Beijing’s plan in the two former colonies, however, has been far from what it has promised. As a result, Hong Kong has witnessed a series of large-scale public movements in recent decades, protesting the erosion of political freedom in the territory. Fearing that their rights and freedom would be further curtailed, millions of Hong Kongers took to the streets last year to demonstrate against a proposed extradition bill, bringing the city to a standstill throughout the second half of 2019.

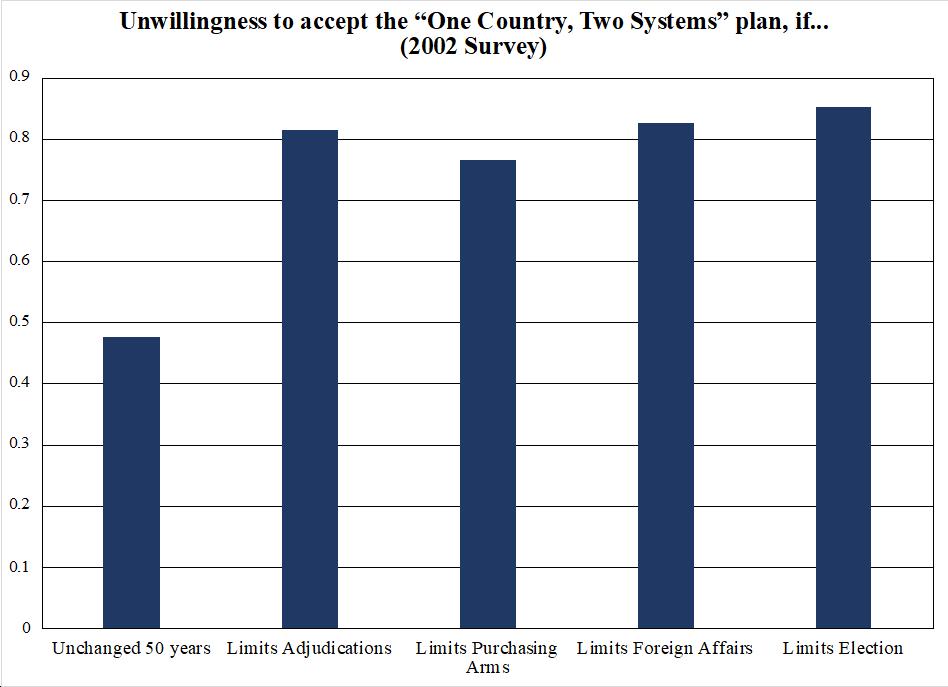

Taiwan citizens have always been skeptical about Beijing’s “one country, two systems” offer, despite the island’s close economic ties with the mainland. In a survey conducted 17 years ago, about 50 percent of the respondents considered Beijing’s unification plan unacceptable even if the plan promised to keep Taiwan unchanged for 50 years. In particular, more than two-thirds opposed the plan when its details were considered. These included limiting Taiwan’s 1) rights of judicial adjudication, 2) ability to conduct foreign affairs, 3) ability to acquire arms from foreign countries, and 4) rights of freely electing public officials. All of these limitations have been imposed onto Hong Kong in one form or another since 1997.

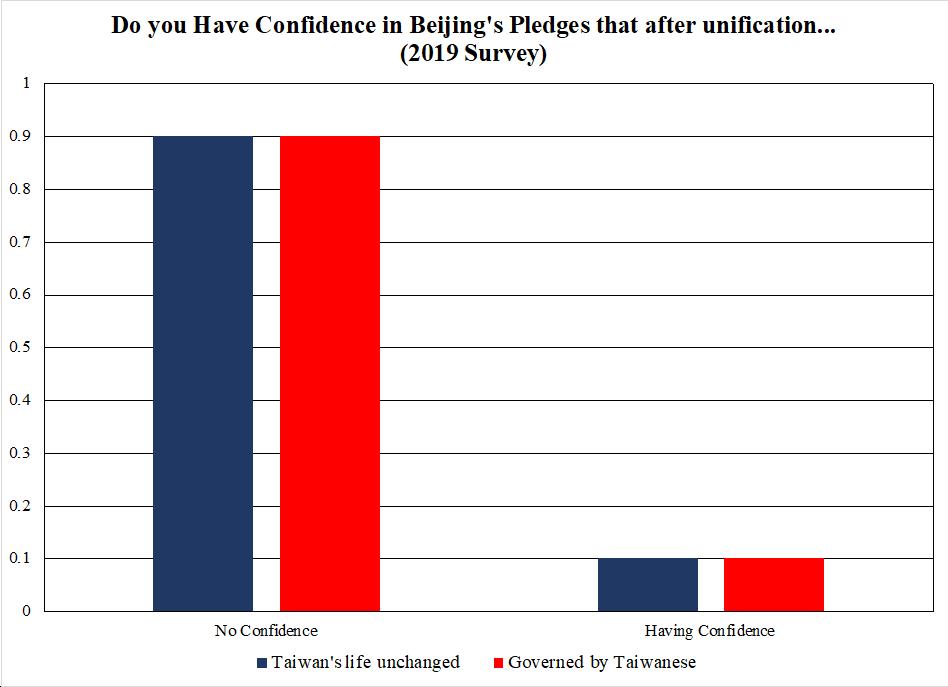

Since then, Taiwan citizens’ skepticism about Beijing’s offer has grown even stronger. A 2019 survey conducted by the Election Study Center of the National Chengchi University in Taiwan shows that 90 percent of the respondents have little confidence in Chinese leaders’ assurances that, under the “one country, two systems” plan, life in Taiwan would remain unchanged, and the government and the military would be governed by the Taiwanese themselves. Such negative sentiments are not surprising as nearby Hong Kong has provided a vivid example of what life would be like if Taiwan were unified with China under Beijing’s plan.

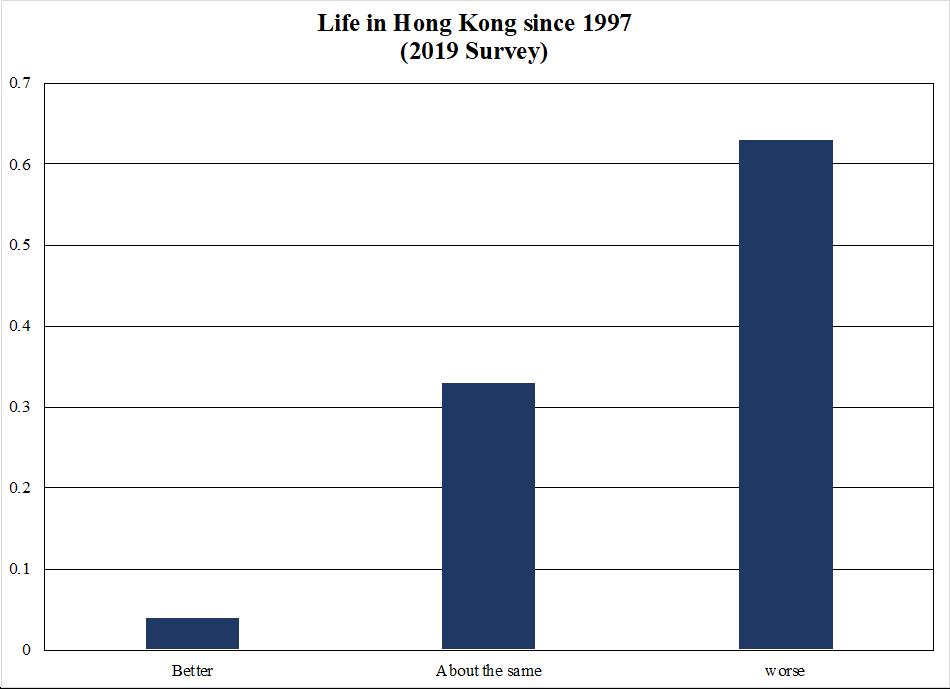

Indeed, the survey shows that over 60 percent of the respondents consider life in the former colony to be getting worse while only 4 percent give a positive appraisal. Taiwan citizens’ views of life in Hong Kong are highly correlated with their confidence in Beijing’s pledges. For those who see the former colony’s promised freedoms as having been eroded since the handover, they show almost zero confidence in Chinese leaders’ promises. Clearly, the erosion of Hong Kong’s rights and freedom since 1997 has heightened Taiwan citizens’ fear of a political integration with the Chinese mainland and hardened their resistance to Beijing’s unification offer. For many Taiwan citizens, “today’s Hong Kong” could be “tomorrow’s Taiwan” if they do not resist.

Early last year, Chinese President Xi Jinping, as all Chinese leaders have done since the 1980s, called on Taipei to enter into unification talks. He indicated that the “one country, two systems” plan was the only viable option for Taiwan, though he hinted that the island country would get a better deal than Hong Kong. While he pledged that Beijing’s effort of unification would be peaceful, Xi also stressed that “we make no promise to renounce the use of force and reserve the option of taking all necessary means.”

Xi’s overture was immediately met with a rebuke from Taiwan President Tsai Ing-wen, who had just won a landslide victory to secure her second term. Countering Xi’s speech, Tsai responded that “Taiwan absolutely will not accept ‘one country, two systems’” framework. She further emphasized that “this opposition is also a ‘Taiwan consensus,’” meaning a position supported by the island citizens. Judging from the above polling results, which span almost two decades, Tsai did not overstate Taiwan citizens’ sentiment. Now that China has unveiled new security legislation that is perceived as curtailing the rights and freedom of the people in Hong Kong, it will only harden Taiwan citizens’ determination to resist Beijing’s unification plan.

T.Y. Wang is University Professor and Chair of the Department of Politics and Government, Illinois State University, Normal, Illinois, USA. He is the co-editor of the Taiwan Voter. (Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 2017) (with Christopher Achen).