Over the past week, news of a long-term strategic pact between China and Iran has caused an uproar among the Iranian public and politicians alike, with both supporters and opponents voicing strong opinions on social media. Iran’s former president, Mahmoud Ahmadinejad, rang alarm bells when he warned of a public backlash totally rejecting the deal should the government fail to consult lawmakers before signing the agreement. In response, government officials were quick to denounce his proclamation as fake news, claiming that there is nothing secretive about the deal. On the contrary, Iran’s government has held the agreement up as a major diplomatic achievement for the country at a time of increasing international isolation.

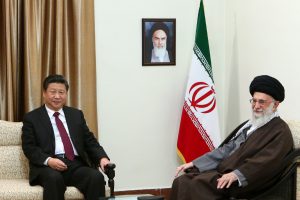

News of the pact first emerged in the immediate aftermath of the Chinese president’s visit to Tehran, where Xi Jinping met Iran’s Supreme Leader Ali Khamenei, who has reportedly approved the deal. Under the agreement, titled “Comprehensive Strategic Partnership between I.R. Iran and P.R. China,” China is supposed to receive preferential access to various sectors of the Iranian economy. However, according to the recently leaked documents, the pact, once enforced, is set to go further than economic cooperation and instead include unprecedented collaborations in transport and logistics in Iran’s southern ports and islands, as well as the country’s defense and security sectors.

How accurate these details are is hard to tell. What is indisputable, however, is that a number of official meetings have already been held and that a pact of some sort is in the making. This, and the ensuing public reaction to the prospect of a deal, in turn, offers important insights into both Iran’s current strategic thinking as well as the evolving nature of China-Iran relations. It also entails an important lesson for Beijing as it pushes through its Belt and Road Initiative.

Beginning toward the end of Akbar Hashemi Rafsanjani’s presidency in the late 1990s, Tehran has been steadily turning toward Asia as part of its Look East strategy. Embattled by its eight-year war with Iraq and dismayed at the slim prospect of improved relations with the West, there has been a general agreement among top officials that Tehran has much to gain and learn from the rising powers of Asia. For instance, Iran not only could implement a modified version of South Korea’s chaebol model to drive industrialization, but it could also find reliable economic partners and energy consumers among the major economies of the continent.

With regard to China in particular, Iran has been drumbeating the importance of the Beijing- Tehran axis as a counterweight to the U.S.-led global order as early as 1995. So far, the expert consensus on the nature of their bilateral ties has centered on the categorization of the two countries as grieved states who, as a consequence, have shown a common desire to engage in aggressive, revisionist regional moves without wanting to start a large-scale war. As such, relations between the two have lacked a sustained degree of coordination and instead have been limited to occasional and opportunistic support for each other’s positions on certain issues.

The agreement would reverse this and thus signals the start of a new strategic partnership between the two whereby, according to the Iranian interpretation at least, they work in concert in order to counter the United States’ dominance in the Middle East. This goal is clearly captured in a recent editorial in the conservative daily Javan titled “The Lion and Dragon Pact.” In it, the author claims that the strategic partnership would enable Iran not only to avoid isolation but also to mount a serious challenge to U.S. supremacy in the Middle East. However, what the author fails to mention is that the deal would increase Iran’s reliance on China in its conduct of foreign affairs; a bitter reality that showcases yet another painful turnaround from the country’s revolutionary ideals.

Inherent in the revolutionary slogan of “neither West nor East” was a desire for independent foreign policymaking and a departure from being a client state. It is not at all clear if Tehran can do so once it is in a partnership with China. Instead, its ability to conduct an independent regional policy would slowly fade away as it must take into account the priorities of its more powerful patron. In other words, Beijing is unlikely to allow Iran to implement policies that are deemed detrimental to China’s own interests and/or reputation in the region. Its angry reaction to Iran’s Health Ministry spokesperson complaining about China’s initial handling of COVID-19, which led to the issuance of multiple formal apologies from Tehran, is a clear indication of the Chinese government’s likely attitude toward its partners: total obedience first, mutual respect second.

Looking at it from the perspective of Iran’s regional foes, however, this might be a welcome development. Given China’s strategic objective of cementing diversified relations, remaining neutral on regional issues, and strengthening its relations with Saudi Arabia and Israel as reliable energy and technology partners, respectively, Beijing might be better positioned to trim Iran’s regional behavior. Once again, Iranian officials are in for a bad surprise if they think that a strategic partnership with Beijing would enable them to expand their influence and agenda in the region. As most recently stated by its foreign minister, China neither has the will nor the capabilities to become another United States, and Beijing is not going to make the same mistake as Washington has by taking sides in regional disputes.

For its part, Beijing is best advised to pay close attention to the Iranian public’s largely negative and highly nationalistic reaction to the prospect of a long-term strategic pact with China. In countries like Iran, where social capital and public trust in the government are in short supply, Chinese investments run the danger of being perceived and/or portrayed as propping up unpopular governments who tend to sacrifice national interests in order to safeguard their own survival. Not only would this tarnish Beijing’s image, but it could also jeopardize its ability to do business with these countries should there be a change of guards at the top of the political echelon.

Nima Khorrami is a Research Associate at The Arctic Institute.