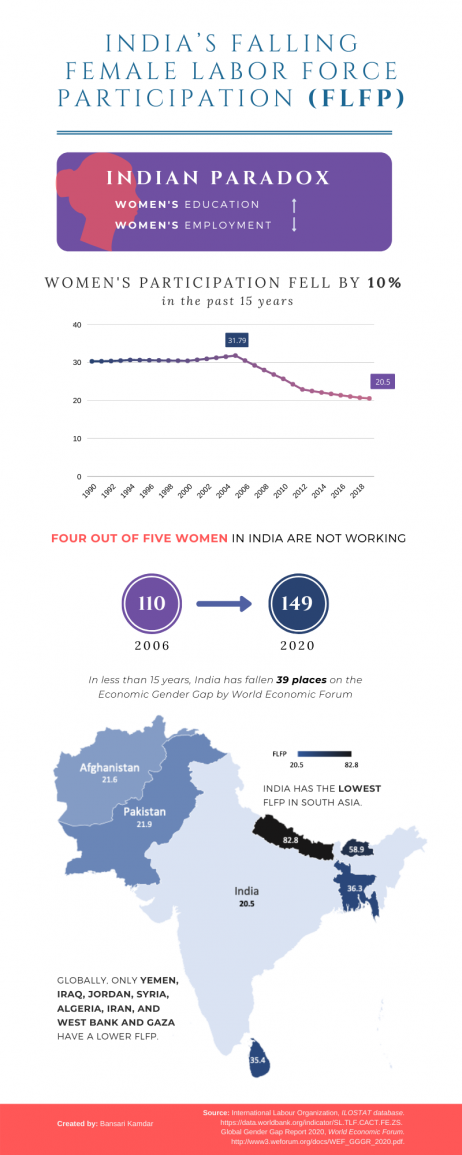

Four out of five women are not working in India. Only Yemen, Iraq, Jordan, Syria, Algeria, Iran, and the West Bank and Gaza have a lower female labor force participation (FLFP) rate than India. In 1990, India’s FLFP was 30.3 percent. By 2019, it had declined to 20.5 percent, according to the World Bank. While the men’s labor force participation rate slightly decreased over time, too, it is four times that of women at 76.08 percent in 2019.

Despite a rising GDP and increasing gender parity in terms of falling fertility rates and higher educational attainment among Indian women, India’s FLFP continues to fall. India’s job stagnation and increasing unemployment in the past few years — a problem that is aggravated by the COVID-19 pandemic — could further worsen this situation.

According to a 2019 report by Google and Bain & Company, women were already the worst hit by India’s unemployment crisis. While the overall Indian unemployment rate was at 7 percent before India’s March lockdown, it was already as high as 18 percent for women. A preliminary study found that Indian women have already lost more jobs than men during the COVID-19 pandemic.

More women entering the workforce is beneficial for both men and women. Research shows that median real wages for both men and women rise by 5-13 percent with a 10 percent increase in FLFP rate in a metropolitan area. Individually, studies have linked women’s wage work to increased autonomy and decision-making power in the household, delays in the age of marriage and first childbirth, and an increase in education for children in the house.

While labor force participation is declining globally on average, women’s participation has increased in high-income countries that have instituted gender-focused policies like parental leave, subsidized childcare, and increased job flexibility. On the Global Gender Gap Index by the World Economic Forum (WEF), India has fallen four places from 2018, now ranking 112 of 153 countries, largely due to its economic gender gap. In less than 15 years, India has fallen 39 places on the WEF’s economic gender gap, from 110th in 2006 to 149th in 2020. Among its South Asian neighbors, India now has the lowest female labor force participation, falling behind Pakistan and Afghanistan, which had half of India’s FLFP in 1990.

Possible Explanations for India’s Declining FLFP

Possible Explanations for India’s Declining FLFP

While greater education leads to greater economic participation for men, it is not the same for women. Researchers have observed a U-shaped relationship between education and labor force participation in India. Women with no education and women with tertiary education display the highest rates of labor force participation among Indian women. The lack of demand for moderately educated women and occupational segregation could explain the Indian paradox of increasing female education and decreasing women’s employment despite India’s economic growth.

Indian women are often required to prioritize domestic work, particularly if they are married due to the cultural and societal expectations of women as caregivers. In the Indian National Sample Survey (NSS) for 2011-2012, over 90 percent of women who did not work were primarily engaged in domestic duties. Around 92 percent of these women stated that their principal activity was domestic work in the previous year because they were “required (needed) to do so,” with 60 percent of women in rural areas and 64 percent in urban areas adding that their primary reason to spend most of their time on domestic duties was that there was “no other member to carry out the domestic duties.”

Women continue to do a majority of housework in India. On average, Indian women perform nearly six hours of unpaid work each day, while men spend a paltry 52 minutes, according to the Organization of Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD). Feminist economists have long debated what constitutes “work” and the invisibility of women’s household labor. In a working paper for the Centre for Sustainable Employment, researchers Bidisha Mondal, Jayati Ghosh, Shiney Chakraborty, and Sona Mitra question the classification of work and argue that domestic duties and women’s other paid but unrecognized work (ex. beggaring or prostitution) should be counted as they “involve the production of goods and services that are potentially marketable and are thus economic in nature.” When these are counted alongside market work, the drop in female labor participation is no longer so evident.

Rather, the researchers noticed a shift from paid to unpaid work from 1993-94 to 2011-12. They find that the total female work participation was greater than that of men in India at 86.2 percent compared to 79.8 percent for men if women’s domestic work and other paid but unrecognized work was counted. There is still some decline in female labor participation, 6.1 percent in the rural areas and 3.8 percent in the urban region, that the researchers attribute to women’s increased involvement in education.

Social stigma against women working outside the house, especially for the those who can afford not to work, continues to influence women’s presence in the labor market. A 2016 survey in the Economic and Political Weekly finds that around 40-60 percent of women and men in rural and urban parts of India believe that married women whose husbands earn a good living should not work outside the home.

Women from poorer households have a higher economic activity rate, suggesting that poor women cannot afford to abide by the social expectation of female seclusion. However, researchers note that as household income per capita increases, women start to leave the workforce. Since family status is linked to women staying inside the home, domestic work becomes more attractive as the family income increases.

Indian women also struggle with well-meaning but discriminatory government policies like the amended India’s Maternity Benefit Act 2017, which increased women’s paid maternity leave from 12 weeks to 26 weeks. This act reinforces women’s role as primary caregivers and increases employer bias, especially in the absence of similar benefits for fathers. Women in India are also not allowed to work in any factory overnight, with Section 66(1)(b) of the Factories Act 1948 specifically stating that women can only work in a factory between the hours of 6 a.m. and 7 p.m. There are no such restrictions on men. Ashmita Gupta finds that this policy had an adverse effect on women’s participation by constraining women’s work hours.

To combat the economic downturn brought on by COVID-19, some states have proposed changes in labor laws. This could disproportionately harm women. Uttar Pradesh, the largest and the most populous Indian state, has suspended 35 of its 38 labor laws for three years, including laws like the Minimum Wages Act, Maternity Benefit Act, Equal Remuneration Act (ERA), and more. Suspension of many of these labor laws could push even more women out of the workforce as employers extend work hours, widen the gender pay gap without the safety of the ERA, and reduce women’s mobility by taking away health and safety mechanisms.

Recent studies have shown that violence against women in public places, particularly the risk of sexual assault and unsafe work environment, discourages Indian women from entering the labor market. In a country ravaged by high rates of violence against women, these states will no longer hold companies accountable for providing safety like transport for night shifts, nurseries, or adequate lighting.

Another big impediment to women’s labor force participation is the gender wage gap. A survey by Avtar Group, a diversity and inclusion consulting firm, finds that women are paid 34 percent less than men for the same job with the same qualifications, despite India’s Equal Remuneration Act of 1976 that mandates equal pay for same work and prohibits hiring discrimination. Indian women perform a double shift at work and home just to earn less than their male counterparts at work, all the while facing down normative, cultural, and legal challenges — pushing many to leave the workforce.