Just three years ago, the World Bank was proud to highlight its growing engagement with China Development Bank (CDB) in Africa. Yet in July this year, World Bank President David Malpass, a Trump appointee, publicly criticized China Development Bank for not participating in the G-20’s Debt Service Suspension Initiative (DSSI) for official bilateral creditors, announced earlier this year.

Malpass’ focus on CDB followed a public statement in April from China’s minister of finance calling on the U.S.-dominated World Bank to participate in the DSSI. So far, neither of the two big banks has budged.

What’s going on? Will the rising hostility between the United States and China make a comprehensive approach to debt relief more difficult in Africa?

Africa and the Pandemic

The COVID-19 pandemic has hit African countries hard. The IMF now estimates that sub-Saharan African economies will shrink by nearly 3.2 percent this year, the worst decline on record. Debt service relief is imperative.

Malpass framed his comments on CDB as an Africa issue. China Development Bank’s “full participation” in the G-20 debt relief effort, he said, was “important to make the initiative work, especially since it has played such an important role in providing development assistance to Africa [emphasis added].”

However, as far as Africa goes, the World Bank president’s focus on China Development Bank appears to be a red herring. As we explain below, with the important exception of Angola, CDB is not a significant lender in the group of African countries that are participating in the DSSI.

The Controversy Over Chinese Lenders

China’s two largest overseas lenders are China Export Import Bank (Exim Bank) and China Development Bank. The World Bank’s definition of official bilateral creditors — those that the G-20 agreed would participate in the DSSI — includes export credit agencies but explicitly excludes government-owned commercial banks, which are considered “private.”

The World Bank confirmed to us earlier this month that as China’s official export credit agency, China Exim Bank has been participating in the G-20 initiative and has concluded agreements with a number of countries.

Our data on China-Africa loan commitments suggest that China Exim Bank has provided close to 75 percent of all Chinese loan commitments in the DSSI-eligible African countries (excluding Angola, which we discuss below) and China Development Bank only 5 percent. Chinese commercial banks and companies account for the rest.

Although China Exim Bank is participating in the DSSI, Chinese officials have argued that China Development Bank is a commercial bank. China would “encourage” CDB to take part, just as other G-20 members were encouraging their commercial lenders and bondholders firms to participate.

To be fair, there is some ambiguity about CDB. In 2008, CDB was officially restructured as a commercial bank. Then, as the Chinese magazine Caijing explains, the global financial crisis hit, and Beijing back-pedaled. CDB became a hybrid: part policy bank, part commercial bank. China can’t have it both ways: Beijing should include CDB as an official bilateral lender in G-20 debt relief.

But for most of Africa, CDB’s inclusion would make little difference.

Angolan Exceptionalism

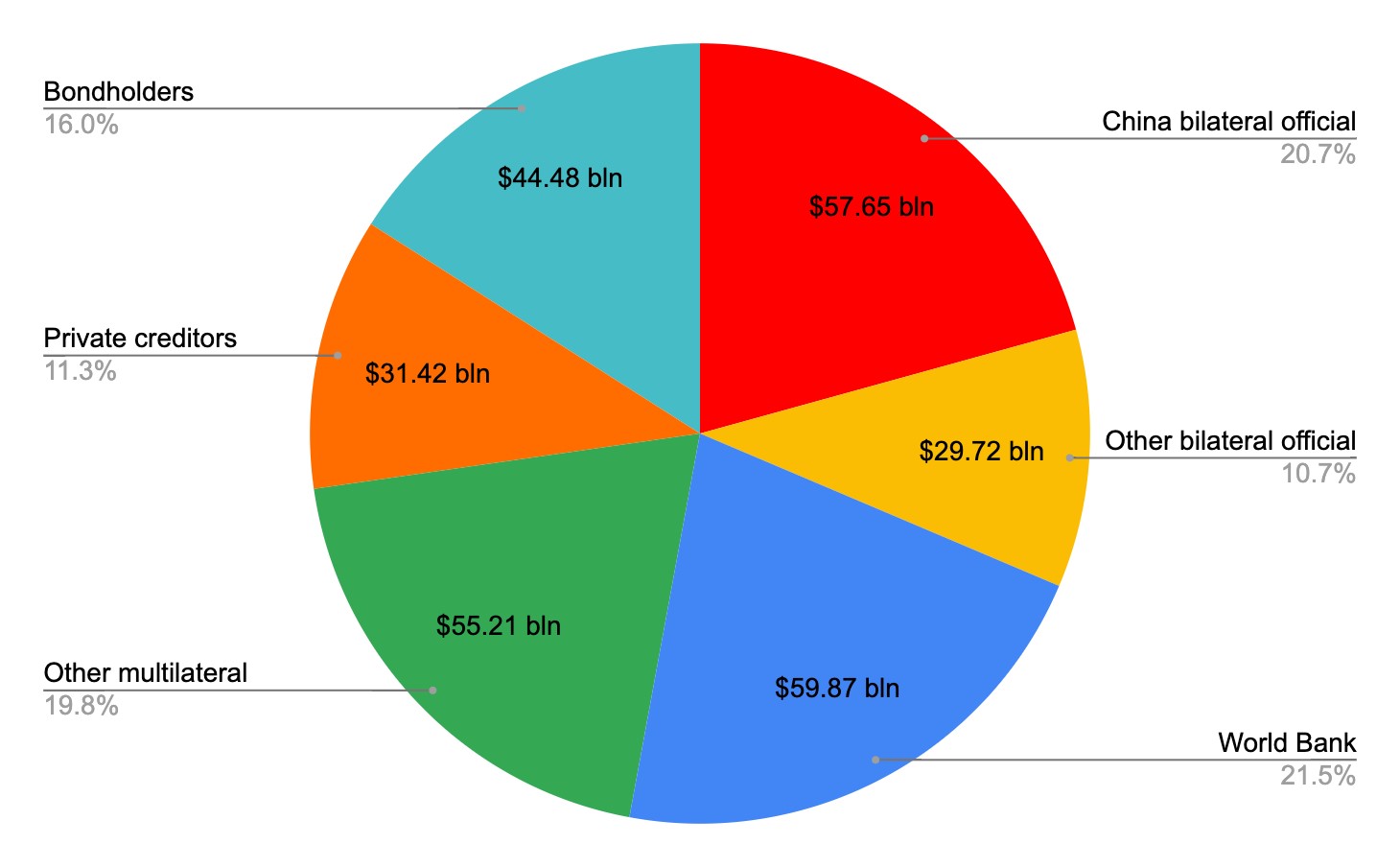

In Africa, 38 countries are eligible for debt relief under the G-20 program. World Bank data indicate that as of 2018, Chinese official lenders accounted for almost 21 percent of public and publicly guaranteed debt in these 38 countries (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Creditors’ debt stock in Africa’s DSSI-eligible countries, 2018. Graphic by CARI using World Bank data.

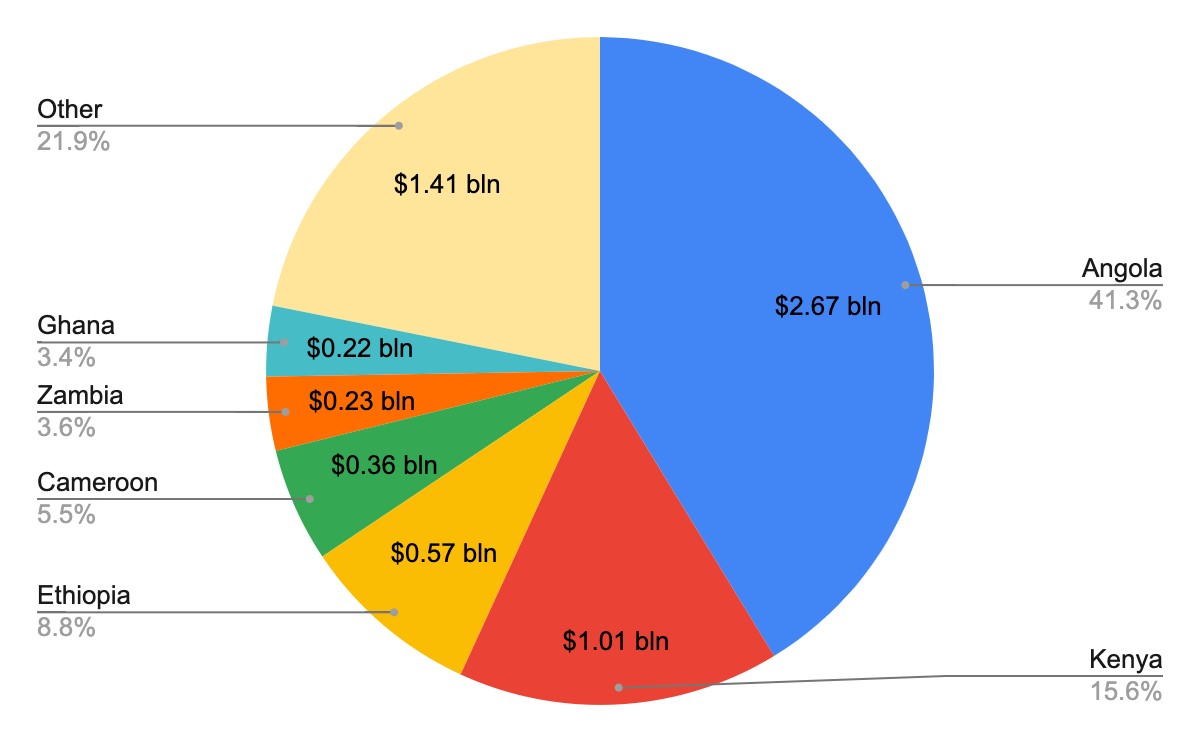

As noted above, the Chinese official creditor debt stock figures for Africa are distorted by the exceptional case of Angola, where Chinese banks believed they had reduced risks by collateralizing their infrastructure loans with Angola’s substantial oil exports to China. Angola accounts for 31 percent of Chinese debt stock, and over 41 percent of all the Africa debt service due to official Chinese lenders this year, in the DSSI-eligible countries (Figure 2).

Figure 2: Official Chinese debt service due in Africa’s DSSI eligible countries, 2020. Graphic by CARI using World Bank data.

China Development Bank is heavily involved in Angola lending. Our data suggest that since 2011, CDB has accounted for 75 percent of all Chinese official bilateral lending in Angola. And in turn, Angola accounts for over almost 90 percent of CDB’s lending to the African countries eligible for the G-20 debt moratorium.

Aside from Angola, only six other DSSI-eligible African governments have borrowed from CDB. Two — Ghana and Kenya — have not joined the DSSI, hoping to be able to continue to access bond markets (the initiative forbids non-concessional borrowing during the moratorium).

As a result, aside from Angola, CDB’s loan commitments to the other 28 African governments currently participating in the DSSI amount to less than $2 billion. Including CDB in the DSSI would be of huge benefit to the 30 million people of Angola but would hardly make a dent in African debt more generally.

U.S.-China Rivalry

If CDB is not actually an important lender in low income Africa, why did Malpass single CDB out as key to the G-20 effort? It’s possible this has more to do with the sharply rising rivalry between China and the United States than deep concern with solving the debt distress caused by this global pandemic.

Take disagreements over whether the World Bank should join the DSSI. China’s Minister of Finance Liu Kun has been vocal in calling for the U.S.-dominated World Bank to join. In April, immediately after the G-20 announced the debt relief agreement, he pointedly urged the World Bank to join in. If not, he said, in language very like that used by Malpass, “the effectiveness of the initiative will be undermined.”

United Nations officials and anti-poverty groups like Bono’s One Campaign are also calling on the World Bank and other multilaterals to join the G-20 effort. So far, Malpass has refused, saying that the multilateral banks need poor countries to keep paying debt service so that they can provide new loans.

Perhaps by focusing on China Development Bank, Malpass was trying to deflect attention from the World Bank’s own reluctance to provide debt relief in Africa.

Furthermore, the focus on CDB — and by extension, China — takes attention away from other actions to mitigate debt distress, such as an expansion of the IMF’s special drawing rights (SDR), a quick infusion of liquidity that has been supported by China, African countries, and Europe, but not the United States.

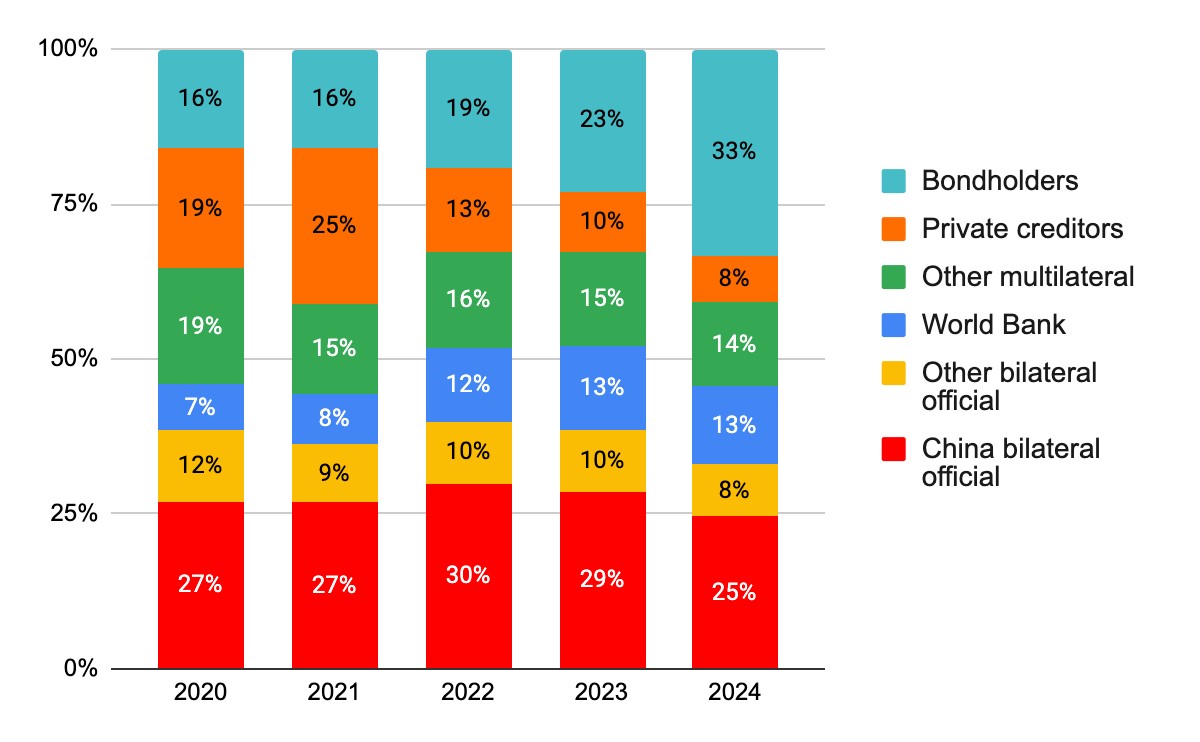

Finally, keeping the focus on CDB obscures the larger issue. Africa’s pandemic-triggered debt problems are not simply a China story. Figure 3 shows debt service that African DSSI countries will owe for the next five years. Multilaterals, bondholders, and private lenders that are not currently providing debt relief will be collecting 61 percent of these countries’ debt service this year and 68 percent by 2024 (Figure 3).

Figure 3: Projected Debt Service in DSSI-Eligible African Countries, 2020-2024. Graphic by CARI using World Bank data.

The World Bank president’s use of the bully pulpit to push China to include CDB could work, but it could also backfire. How long will stakeholders in China continue to participate in a debt relief process where most of the relief is provided by Beijing, while most of the debt is owed to others?

The G-20 agreement was a historic example of cooperation by the world’s largest economies. For the G-20, keeping China on board while bringing these other stakeholders to the table is going to take skillful diplomacy, mutual concessions, and genuine cooperation, not Trump-style confrontation.

Deborah Brautigam is Bernard L. Schwartz Professor of International Political Economy and Director of the SAIS China Africa Research Initiative.