With Joe Biden having chosen California Senator Kamala Harris as his running mate, the 2020 U.S. presidential election tickets are complete. The Democratic National Convention is currently underway; the Republican one will follow next week.

Whatever the outcome of the November election, given economic uncertainty and the unprecedented COVID-19 public health crisis, the next president will have much to address.

Polls currently suggest a double-digit Biden lead over incumbent President Donald Trump, with these data echoed in those battleground states Trump carried in 2016. But to quote former U.K. Prime Minister Harold Wilson, “A week is a long time in politics.” And a lot could certainly happen in two and a half months. How should those of us outside of the United States view the November election? And what should U.S. allies expect if Trump does, polls notwithstanding, win a second term? Will they be able to rely upon the United States under another four years of Trump?

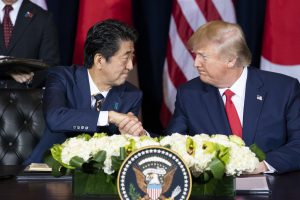

Japan, for example, which counts the U.S. as its only treaty ally, has been challenged by having to court an unpredictable, norm-breaking president who exhibits a bizarre fondness for authoritarian figures, such as the leaders of North Korea and Russia. Trump has also made a number of controversial moves without any indication of long-term strategic thinking, such as the sudden courting of North Korea’s Kim Jong Un. After the initial photo ops concluded, there was no progress in disarmament talks and it now appears as though Trump has lost interest. As informed skeptics predicted, North Korea has continued to develop its missile and nuclear capabilities. The Trump-Kim summit produced nothing to promote either regional stability or U.S. leadership.

We should consider other major policy reversals that concern the Asia-Pacific and beyond. On his third day in office, Trump announced the United States’ withdrawal from the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP) which, in former President Barack Obama’s words, would have allowed “America — and not countries like China — to write the rules of the road in the 21st century.” By inviting ardent critics of the Joint Comprehensive Action Plan, such as John Bolton and Mike Pompeo, into the administration, the U.S. disavowal of the P5+1 Iranian nuclear deal was complete. Trump also withdrew the United States from the 190-party Paris Climate Agreement. Notice of the U.S. intention to withdraw from the Reagan-Gorbachev era 1987 Intermediate-Range Nuclear Forces (INF) Treaty was served in February 2019, with the treaty consequently falling in August 2019. To the latter point, the scrapping of a treaty that eliminated this dangerous class of nuclear weapons from the U.S. and Russian stockpiles only adds further concerns to an already negative nuclear proliferation outlook given the advancing WMD programs of North Korea and others.

If the past three and a half chaotic years serve as any indicator, a second Trump term would likely be even more volatile and unpredictable than the first. Moreover, and more worryingly, perhaps we have, to date, only seen a glimpse of a new world in which America negates its global leadership role.

New foreign policy initiatives are not unusual when an administration takes office. In the past, such changes have formed part of an overall policy doctrine. In the case of Trump, though, the approach appears to be simply targeting and rescinding landmark policies with little or no consideration of the consequences or the merits of such abrogation. Disruption, in and of itself, appears to have become the objective, and not merely a means to an end. Furthermore, major policy shifts, historically, were debated, analyzed, and rigorously contested. Yet with a submissively compliant set of Republicans in Congress, oversight has vanished, with the GOP leadership assuming no more than a procedural rubber-stamping role.

To the Trump base, America’s standing in the world is of little or no interest. And this disinterest, coupled with a lack of understanding, has led to a myopically domestic populist policy agenda. Explicitly and implicitly, the “America First” and “Make America Great Again” mantras ignore America’s allies in favor of a short-term “transactional” form of politics in which Trump’s penchant for isolationism and inability to comprehend a complex and multilayered international security environment are laid bare.

Where foreign policy is of utility to the president, however, is in promoting an “America as victim” narrative. Fitting neatly into a narrative of foreigners stealing the jobs of Americans and trade agreements taking advantage of U.S. largesse is the argument that the United States is unfairly footing the bill to defend its friends. Specifically, the president argues that NATO allies, South Korea, and Japan should pay more. In this assertion, Trump has a point. In base dollar terms, the U.S. does pay much more than its allies. Discourse is legitimate and an ongoing dynamic reassessment of defense burden-sharing is appropriate. But a decision in terms of how much each nation pays needs to be accompanied by an appreciation of the delicate military and political considerations balancing a multitude of countervailing incentives that have determined existent defense expenditure. Yet, to Trump, the only consideration is a “red meat” message to a domestic political base that views allies’ defense spending as an act of opportunism, funded once again by a well-meaning but naïve United States.

Trump’s electoral appeal is, however, waning. With his 2020 re-election campaign underway, the president is failing to appeal to new voters or even to retain those swing voters who gave him his marginal victory in 2016. With polls against him, the behavior of the president, his administration, and his campaign have become increasingly desperate, even to the extent of propagating QAnon and other conspiracy theories. There is even the absurd assertion that Senator Harris, born in Oakland, California, is ineligible to serve as vice president, based on a calculated and mendacious misreading of the constitution. And, apparently, the deliberate sabotage of the United States Postal Service is underway in an attempt to prevent postal voting.

With November 3 fast approaching, Trump remains incapable of articulating a second term agenda. Perhaps he himself does not even know. U.S. allies can only watch anxiously as the election countdown progresses. There are, thus far, no grounds to anticipate any greater stability or support should a second Trump term transpire. Rather, there is much cause for concern.

Yukari Easton is a researcher and a 2014-2015 ACE-Nikaido Fellow at the East Asian Studies Center at University of Southern California whose research focus is upon international relations, diplomacy, and security issues in the Asia-Pacific region. Previously, she worked for ten years in international banking in Europe and Asia.