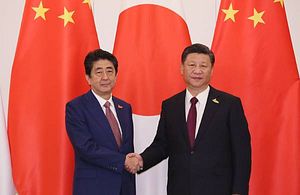

Japan’s Prime Minister Abe Shinzo, considered a strong leader in several foreign capitals, including Beijing, abruptly announced last Friday that he is resigning for health reasons. But writing for the New York Times last Sunday, a leading political scientist in Japan, Koichi Nakano, did not believe a relapse of ulcerative colitis was the only reason why Abe abruptly announced his decision to quit.

Like Nakano, most analysts both at home and abroad have cited multiple factors preventing Abe from extending his record as Japan’s longest serving prime minister – seven years and eight months, to date. At the time of Abe’s “surprise” announcement, his disapproval ratings stood at 34 percent, the highest ever during his record tenure. Among the most prominent reasons for his rising unpopularity include a negative view of Abe’s response to the pandemic and allegations of a series of scandals and controversies he is still mired in – including extravagant, lavish events such as “the cherry blossom viewing party” that the prime minister hosts every year but is paid for by taxpayer money. Other factors behind his dropping popularity include: a dismal failure in rebuilding the Japanese economy as promised by his signature “Abenomics”; the controversial re-militarization of Japan, which saw massive street protests by the anti-war Japanese people; and last but not least the ill-conceived “Abenomasks” policy, under which each household was promised two washable cloth masks – the plan not only irritated the people but was immediately dismissed as “useless” and “inefficient.” The endless list of the Abe government’s failures goes on and on, analysts are telling us.

Interestingly, neither Japanese experts nor Japan watchers in the West have seen a possible connection between the prime minister’s resignation and the worsening U.S.-China rivalry. On the other hand, as the South China Morning Post put it, Abe’s “eight-year spell in office saw several ups and downs in Japan’s relations with Beijing, the most recent being the straining of ties between Tokyo and Beijing due to the introduction of a national security law in Hong Kong earlier this year.”

To be fair, some analysts in Japan haven’t lost sight of the predicament Japan finds itself in: The country continues to depend on China economically while remaining dependent on the United States for security. “Aligning with the U.S., but at the same time maintaining functioning relations with China, is Japan’s top priority…this will not change,” Michito Tsuruoka, associate professor at Keito University in Tokyo, told SCMP on the day Abe announced his decision to step down.

The authorities in Beijing have refused to react to political developments in Japan, preferring to maintain a stoic silence — even while knowing full well the implications of a new leader in Tokyo. Chinese foreign ministry spokesperson Zhao Lijian declined to comment both on Abe’s resignation and on the leadership succession.

Chinese experts, however, have not only been forthcoming but even voiced differing opinions.

Liu Jiangyong, a Japanese affairs expert at the Tsinghua University in Beijing sees a “friendlier” post-Abe Japan. But Liu does not rule out continuation of the current Abe government’s foreign policy approach of trying to maintain a balance between Beijing and Washington in the event of U.S. President Donald Trump winning a second term. “If Trump wins and continues his aggressive policies with China, Sino-Japanese relations would be affected because Japan is, after all a key ally to the U.S. but Joe Biden may adopt a less extreme approach to Beijing,” Liu told SCMP.

Some Chinese scholars have been more appreciative of Japan’s mature approach toward Beijing under Abe in recent years, be it in the context of the two East Asian neighbors’ territorial dispute in the East China Sea — where Tokyo is not keen on starting a direct conflict with Beijing — or more recently, in tackling tensions with China over the COVID-19 pandemic and over Beijing’s imposition of a national security law in Hong Kong. “His [Abe’s] policy is one that emphasizes being both realistic and pragmatic,” according to Huang Dahui, an IR expert with Renmin University in Beijing.

Sima Nan, the stage name of a well-known nationalistic commentator, on Monday displayed a more hard-line approach toward Abe’s Japan. Sima dismissed a Keito University professor’s predictions about Japanese policies toward America and China in the post-Abe era as untenable. Overall, the take sounded like a warning to whoever is going to succeed Abe: “If you wish to reap China’s economic benefits, but at the same time you do not wish to sin against both China and America, this will no longer be possible in the face of the irreversible worsening U.S.-China bilateral relations.”

In 2007, Abe resigned for the first time from the prime minister position. Then, as now, the mainstream media both in Japan and in the West cited the following reasons for the fall of the government: Abe’s failing health, his controversy-plagued government, which foundered on scandals and gaffes, Japan’s decision to continue its military’s participation in the Afghanistan war, and most of all Abe’s rising unpopularity. In China, on the contrary, it was widely believed that a significant factor leading to Abe’s resignation in 2007 was his failure to maintain a perfect balance in Tokyo’s relations with the United States and China. Abe, who had just become prime minister, actually wanted to revive the fledgling Japanese economy by developing good relations with China and at the same time he wanted to establish a China-Japan-South Korea free trade area. Unfortunately for Abe, the United States found this to be against its national interest.

Abe proved to be wiser as he began his second tenure as Japan’s prime minister in 2012, Chinese Japan watchers say. He won former U.S. President Barack Obama’s confidence in Japan as a reliable ally committed to free trade and a stronger military ally in the Asia-Pacific region. Notably, Abe and Obama reached an agreement that would extend Japan’s ability to come to the defense of the United States. However, with the change of guard in the White House following the Trump victory in 2016, Abe’s policy of wooing the United States faced a huge challenge. And now as the worsening U.S.-China rivalry is accelerating, Abe has fallen sick once again.

In the words of veteran “leftist” Chinese foreign affairs observer Zhang Zhimin, if U.S.-China relations today were at the same level as before Trump launched the trade war or even before the outbreak of COVID-19, it would have been okay for Japan to still dabble with both parties. But now Japan is caught in a dilemma of having to choose between China and the United States. No wonder, Zhang uses the famous Chinese saying “one cannot have fish and bear’s paws at the same time” to describe Abe and Japan’s predicament. The saying actually means that in order to get something, one must sacrifice something.

In other words, what Zhang is implying is that Abe’s timing to resign both times has been perfect. And both times, his resigning in the middle of worsening U.S.-China tensions was not a coincidence.

Hemant Adlakha is professor of Chinese at the Jawaharlal Nehru University, New Delhi and Honorary Fellow, Institute of Chinese Studies, Delhi