Tensions between Japan and China over the Senkaku/Diaoyu Islands dispute have recently increased. Japan’s Defense White Paper released in July 2020 stated that China has “relentlessly continued attempts to unilaterally change the status quo by coercion in the sea area around the Senkaku Islands” and that “Japan cannot accept China’s actions to escalate the situation.” Lt. General Kevin Schneider, commander of U.S. Forces Japan, stated that “the United States is 100 percent, absolutely steadfast in its commitment to help the government of Japan with the situation in the Senkakus.”

Meanwhile, a growing chorus of voices in Japan has been calling on the Japanese government to cancel Chinese President Xi Jinping’s state visit to Japan because of the crackdown of dissidents in Hong Kong and China’s aggressive behavior near the Senkakus. The pandemic has already forced the postponement of the historic bilateral summit in Tokyo which was originally slated for spring 2020.

At a time when U.S.-China relations are deteriorating rapidly, it is puzzling that Xi would risk jeopardizing his state visit to Japan by escalating tensions over the Senkaku/Diaoyu Islands. Maintaining the momentum of China-Japan rapprochement, which began in spring 2017, would serve China’s interests because greater stability in China-Japan relations might help to moderate U.S.-China rivalry. So why does China appear to be escalating tensions with Japan over small, uninhabited islets in the East China Sea? A closer examination of recent developments yields a more complicated picture than the popular view of one-sided Chinese escalation.

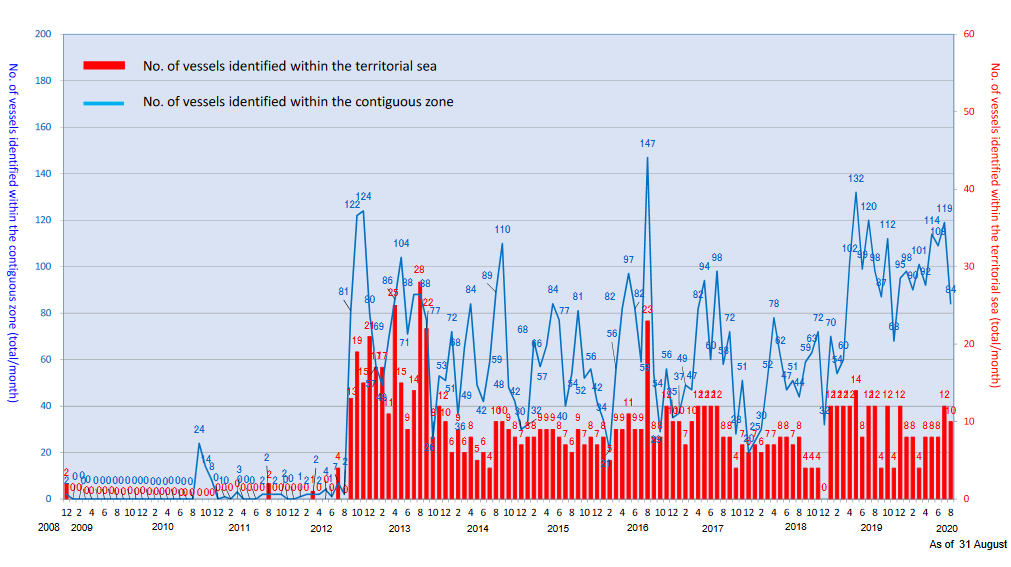

According to Japanese observers, China has been aggravating tensions by increasing the presence of China Coast Guard (CCG) vessels in the contiguous zone of the Senkaku/Diaoyu Islands. The frequently cited graph put together by the Japan Coast Guard (JCG) shows that the number of Chinese official ships inside the contiguous zone increased dramatically starting in April 2019. In the 17-month period from April 2019 through August 2020, Chinese vessels were inside the contiguous zone 456 days out of 519. In the previous 17-month period from November 2017 through March 2019, Chinese vessels were inside the contiguous zone 227 days out of 516.

This near constant Chinese presence in the contiguous zone, which lies between 12 nautical miles (nm) and 24 nm of the Senkaku/Diaoyu Islands, is no doubt irritating and appears threatening to Japan. Nevertheless, foreign ships sailing within the contiguous zone is not a violation of international law. According to Article 33 of the U.N. Convention of the Law of Sea, ratified by both China and Japan, the contiguous zone allows a coastal State to (a) “prevent infringement of its customs, fiscal, immigration or sanitary laws and regulations within its territorial sea” and (b) “punish infringement of the above laws and regulations committed within its territory or territorial sea.” In other words, Japanese authorities can take actions in the contiguous zone against those violating laws and regulations within Japan’s territory and territorial sea, but the contiguous zone does not demarcate the sovereign waters of Japan. Therefore, foreign ships enjoy high sea freedoms in the contiguous zone as long as they do not counter coastal state rights regarding the exclusive economic zone.

So why is China now maintaining a near constant coast guard presence in the contiguous zone of the Senkaku/Diaoyu Islands? One factor may be efficiency. The ports of CCG ships are between 180 and 270 nautical miles from the islands, which means that it takes about 8 to 12 hours to make the trip. After the Japanese government purchased three of the islands in September 2012, China moved to challenge Japan’s administrative control of this territory by regularly entering the territorial sea. To undertake this mission, it would be more efficient for Chinese vessels to linger in or near the contiguous zone for many days and from there make entry into territorial waters rather than shuttling back and forth between the Chinese coast and the islands. Moreover, the modernization of CCG ships may facilitate staying inside or near the contiguous area for a lengthy period of time.

Another explanation of the contiguous zone presence may be deterrence and crisis prevention.

By maintaining a regular presence of ships in the contiguous zone, the CCG can deter provocative behavior by non-governmental actors, including activists from mainland China, Taiwan, and Hong Kong as well as from Japan. There are indeed many rumored and confirmed cases of civilian Chinese activists being coerced away from approaching the disputed islands. While the CCG presence in the contiguous zone may suggest further Chinese “salami-slicing” in the East China Sea, it may also represent a more “professionalized” phase of gray-zone competition and sovereignty dispute management whereby the central government has more precise control of the situation by preventing trouble-making by civilian actors that could undermine national interests and policy.

In addition, the way the JCG presents its data may give a misleading picture of Chinese activity near the islands. By depicting the daily number of Chinese vessels that were present per month in the contiguous zone, the JCG’s widely cited graph could give the impression that over a hundred different Chinese ships have been in this area.

This graph from the Japanese Ministry of Foreign Affairs shows the number of Chinese vessels reported within the Senkaku Islands’ contiguous zone and territorial sea each month.

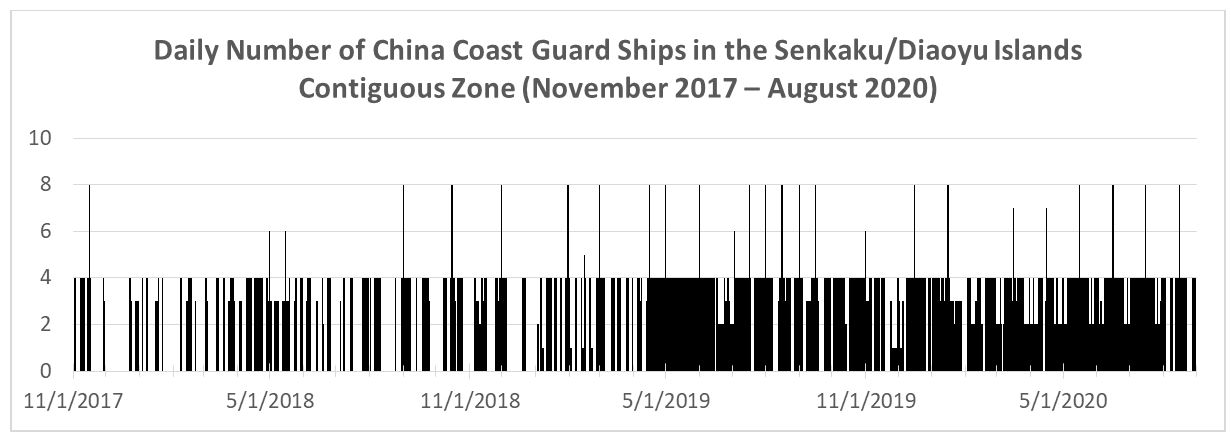

If one took the data in the JCG Japanese-language reports and created a bar graph that showed the number of Chinese ships in the contiguous zone per day, then what becomes clear is the constancy of the Chinese presence, not an increase in the number of ships. The periodic spikes to the number of vessels in the graph below indicates a rotation in the CCG ships maintaining a presence in the contiguous zone.

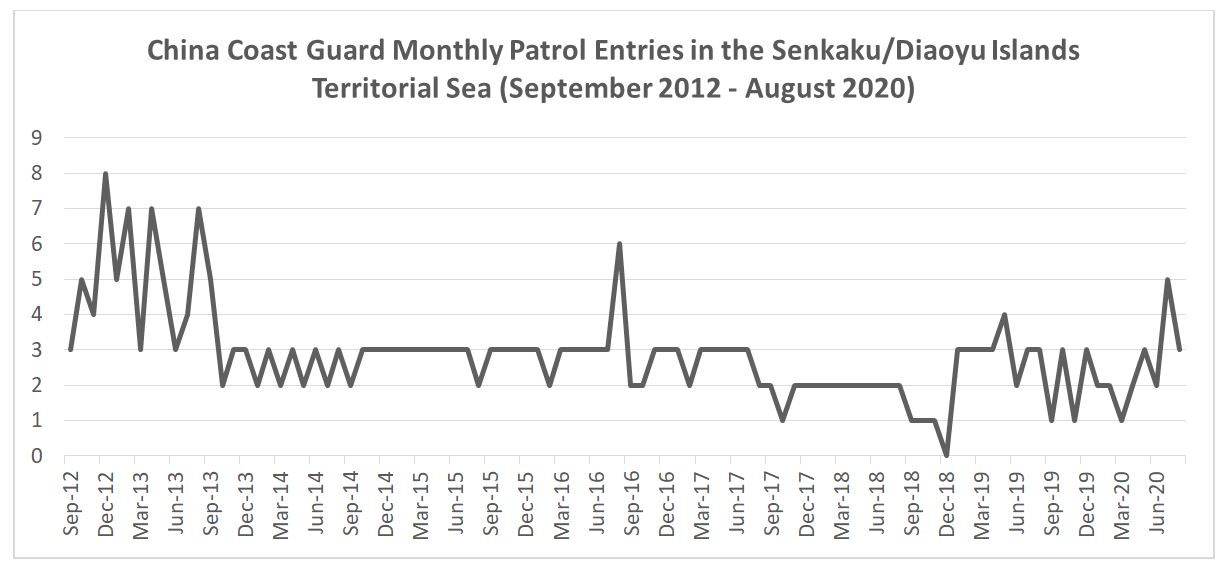

While this constant presence is troubling to Japan, the more salient indicator is the number of Chinese patrols (not the number of ships) inside the territorial sea of the islands, which Japan sees as an explicit violation of its territorial sovereignty. The graph below depicting these patrols inside the territorial waters from September 2012 to August 2020 shows that there has been a stabilization of these patrols to between one and three per month rather than an escalation. Since October 2013, there have been only three months in which CCG patrols in the territorial waters exceeded three: six in August 2016, four in May 2019, and five in July 2020. These specific cases are explained below.

According to Japanese observers, another sign of Chinese escalation was the tailing of a Japanese fishing boat operating inside the Senkaku/Diaoyu Islands territorial waters in early May 2020. Although the JCG initially reported that this tailing behavior was unprecedented, the JCG later corrected the statement by saying that Chinese vessels had followed Japanese boats inside the territorial waters on four previous occasions since 2013. Another case of the CCG tailing Japanese boats occurred in early July, reinforcing the interpretation of Chinese escalation. In April 2013, Chinese official and JCG vessels followed boats carrying Japanese nationalists to prevent them from landing on the islands. The more recent cases of Chinese tailing of Japanese boats, however, requires an analysis of Japanese local fishing interests as well as nationalist activities.

The regular CCG presence near the Senkaku/Diaoyu Islands after September 2012 has discouraged Japanese fishing boats from operating in the area, especially within the territorial sea. According to some media reports, the JCG has even warned Japanese boats not to provoke Chinese state vessels by fishing near the islands. In other words, after the September 2012 island nationalization crisis, Japanese fishing boats have tended to refrain from fishing inside the territorial waters of the disputed islands. At the same time, the fishing agreement between Japan and Taiwan concluded in April 2013 angered Okinawa fishing interests, especially those from the Yaeyama Islands, because competition from Taiwan has reduced the available catch. The combination of the 1997 Japan-China and the 2013 Japan-Taiwan fishing agreements allowing Chinese and Taiwanese fishing boats to operate in a large area surrounding the Senkaku/Diaoyu Islands except for the territorial sea has economically strained local Japanese fishermen.

With resentment growing among Yaeyama fishing interests, one fisherman from Ishigaki City began in October 2017 to talk openly about catching fish near the Senkakus and using such fish as a “brand” to boost sales. Also a local nationalistic politician, this fisherman declared he wanted to monitor CCG ships. In late May 2019, his boat entered the Senkaku territorial sea, causing two CCG ships to tail it and depart from the routinized patrols inside the territorial waters. As a consequence, the tally of CCG patrol entries for May 2019 increased to four. After this incident, the Ishigaki fisherman told local journalists that the JCG vessel that had moved toward his boat used a speaker to instruct him not to provoke the Chinese official ships. Soon thereafter Okinawa Governor Denny Tamaki told the press that fishing boats should refrain from engaging in provocative actions when China Coast Guard vessels are nearby. The Ishigaki City Assembly then passed a resolution criticizing the governor for undermining Japan’s territorial interests.

In early May 2020, a man from Yonaguni Island who runs a recreational fishing company decided to go into the Senkaku/Diaoyu territorial waters. Because his tourist business had dried up due to COVID-19, he wanted to fish inside the territorial waters. This action led two CCG vessels to follow the Yonaguni boat over a two-day period. Then on June 20, an Ishigaki-based fishing boat accompanied by a boat of the nationalistic Channel Sakura television network departed for the Senkaku Islands and fished in the territorial waters the next day. For about four hours, four CCG vessels monitored the Japanese boats while remaining in the contiguous zone. The Chinese vessels made their patrol inside the territorial waters after the Japanese vessels returned to Ishigaki on June 22. The JCG stated that the Chinese Coast Guard ships had not approached the two Japanese boats. On the very day that the boats returned to Tonoshiro Fishing Port on Ishigaki, the Ishigaki City Assembly passed a resolution to change the name of the area encompassing the Senkakus from “Tonoshiro” to “Tonoshiro Senkaku.” This action provoked protests from both China and Taiwan.

With tensions brewing, three boats from Ishigaki sailed into the Senkaku/Diaoyu territorial sea to fish in early July. This prompted two CCG ships to tail the boats inside the territorial waters for four straight days, and the JCG vessels moved between the CCG ships and Japanese fishing boats to prevent an altercation. During this face-off, the CCG ships stayed in the territorial waters continuously for over 39 hours, the longest period since the September 2012 nationalization. As a consequence, there was a spike in the number of CCG patrol entries inside the islands’ territorial sea to five in the month of July 2020. The Chinese and Japanese governments lodged protests against each other through diplomatic channels. China reportedly asked the Japanese government to prevent Japanese boats from fishing in the territorial waters of the Diaoyu Islands and block the name change approved by Ishigaki City. Japan vigorously rebuffed the Chinese demand. Japan fears that Beijing is using these developments to weaken Japanese control over the islands and strengthen its sovereignty claims. But from the Chinese perspective, local fishing entities encouraged by Japanese nationalists are provoking China to respond to protect its sovereignty claims.

Finally, Japanese policymakers and analysts are concerned that China uses Chinese fishing boats as an instrument of “salami-slicing” to undermine Japan’s territorial sovereignty. In August 2016 after the lifting of China’s seasonal fishing moratorium, a fleet of about 200 to 300 Chinese fishing trawlers sailed near the Senkaku/Diaoyu Island area accompanied by CCG ships. The CCG vessels maneuvered in and out of the territorial waters, suggesting that they were policing Chinese fishing boats. This behavior sparked concerns in Japan that China was using fishing boats along with CCG ships to weaken Japan’s administrative control. Although a definitive explanation of this episode has not come to light, China may have been signaling its hostility to Prime Minister Abe Shinzo, who at the time had been using various international fora to criticize China’s activities in the South China Sea.

After Abe moved to improve relations with China by deciding to send Liberal Democratic Party Secretary-General Nikai Toshihiro to the May 2017 Belt and Road Forum in Beijing, the swarming of Chinese fishing boats to the Senkaku/Diaoyu Islands did not occur again in August 2017, 2018, and 2019. On August 3, 2020, however, the nationalistic Japanese newspaper Sankei Shimbun reported that China had indicated that a large flotilla of Chinese fishing boats would go to the Senkaku Islands after the end of the seasonal fishing ban and Japan had no right to stop this. In a press conference the next day, Foreign Minister Motegi Toshimitsu denied that the Japanese government had received such “an advance notice” from China. Nevertheless, the Japanese government seemed concerned enough to use diplomatic channels to ask China to avoid a situation of Chinese fishing boats surging near the Senkaku area. Japan allegedly warned China that if Chinese fishing boats came in large numbers, Japan-China relations would be destroyed. While it’s unclear whether the Japanese diplomatic message was behind this, local Chinese officials warned Chinese fishermen to stay away from the disputed waters after the lifting of the summer fishing ban. As a result, China and Japan avoided a crisis in bilateral relations.

Although Japan must remain vigilant about protecting its territorial interests, Tokyo should avoid inflating the Chinese threat and should continue to work with Beijing to prevent crises and the militarization of the Senkaku/Diaoyu Island issue. One of Abe’s important legacies is his pragmatic partnership with Xi to improve Japan-China relations since spring 2017. Consistent with the November 2014 four principles that China and Japan forged to improve bilateral relations, both countries should be careful to avoid incidents and escalatory behavior regarding the Senkaku/Diaoyu Islands that will unravel this Abe legacy. At a time of intensifying U.S.-China competition and conflict, promoting Japan-China rapprochement by moving ahead with Xi’s planned state visit to Japan will contribute to peace and stability in the Asia-Pacific region.

Mike Mochizuki holds the Japan-U.S. Relations Chair in Memory of Gaston Sigur at George Washington University.

Jiaxiu Han is an MA student in Asian Studies and a research assistant at George Washington University’s Elliott School of International Affairs.