The Indian political arena features an interesting imbalance in which one party dominates the central government but maintains a disproportionate position in state governments.

In 2019, the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) won 303 of 543 electable seats for Members of Parliament (MPs) in the lower house of Indian Parliament (the Lok Sabha). At the same time, however, its results in state elections, while impressive during the 2014-2018 period, have waned. In some states the party has gone through ups and downs, and it has lost control of some of the bigger and more populous regions. As of now, the BJP has 1,305 members across state-level legislatures, out of a total of 4,123 (these members are termed Members of Legislative Assembly, MLAs for short). This means that across India, 55 percent of MPs but just 31.6 percent of MLAs belong to the BJP.

To be sure, the latter number is not low by itself in Indian history – it is just that it is in disproportion to the former number. One would perhaps expect a party that won so resoundingly on the national level to be more predominant on the regional tier, too.

A similar disproportion occurs when it comes to the states ruled. The highest point of this disparity so far came around the end of 2019, when the BJP was ruling 15 of India’s 28 states. This statistic, by itself, is a good result, and a clear confirmation of the party’s domination. Moreover, as of now the party has climbed up to 17 states (its biggest success being the recapturing of Madhya Pradesh by poaching some of the lawmakers).

Of these, however, it rules five states with other partners, among which it is a significant part of the ruling coalition in three (Bihar, Nagaland, and Sikkim), and an insignificant part in two others (Meghalaya and Mizoram). Further, of the 15 states where it has a significant presence in the government, six are small by Indian standards (Goa, Arunachal Pradesh, Manipur, Tripura, Nagaland, and Sikkim). This leaves us with nine states where the BJP rules and the population of which is large enough to translate into meaningful results on the national level.

Moreover, out of the five states that send the highest number of lawmakers to the federal Parliament – Uttar Pradesh, Maharashtra, West Bengal, Bihar, and Tamil Nadu – the BJP is currently ruling in two: Uttar Pradesh and Bihar. But in the latter state Modi’s party is a junior partner in a coalition. Of these two, Uttar Pradesh is far more important than any other state. Even more generally, of India’s 10 highest-represented states – the MPs from which would be numerous enough to provide a stable majority on the national level – the BJP now rules just five (Uttar Pradesh, Bihar, Madhya Pradesh, Karnataka, and Gujarat).

One obvious reason behind this is that many voters make different choices in national and state elections (and this is also hardly new in Indian politics). There are many strong regional parties in various states but on the national level there is no alternative to the BJP’s predominance at present. Thus, when it comes to central elections, a considerable part of the electorate may assume that the BJP is the only party that can deliver – or, indeed, the only party that can win.

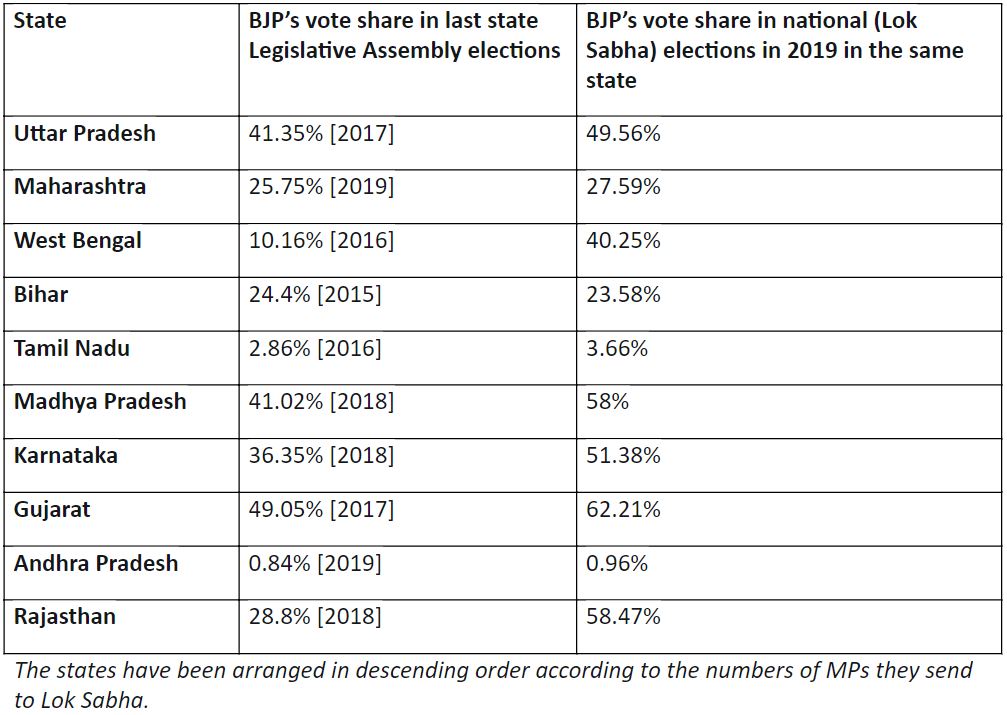

This can be illustrated by comparing the party’s vote share in the last state and general elections in the 10 regions that send the highest number of MPs to the Lok Sabha.

In some cases, such as Bihar or Maharashtra, the BJP’s vote share is very similar in both types of elections. However, in as much as six of 10 politically crucial states its tally in the national elections has been much higher than in the last assembly elections in the same state. This translated into millions of votes.

The last assembly elections in these states were held at various times and in each case regional circumstances would have to be considered. The most recent state elections in West Bengal were held in 2016, so the fact that in 2019 the BJP achieved a four times higher vote share may not only be because these were two different kinds of elections but also a reflection of the party’s growing popularity in that particular state. Elections in Rajasthan and Madhya Pradesh were held just before the national vote. In both cases, the BJP’s results in the assembly elections, while not bad in of themselves, were not enough to achieve a clear edge. In both cases Modi’s party ended up neck-to-neck with its rival and eventually lost the elections. Soon after, however, the same two states showed their clear preference for the BJP in the national poll, as more than half of their electorate offered their votes to the party.

Another major factor that partially explains this disparity is money. There were periods in modern Indian history when acquiring resources in larger states was crucial even for national parties. But this does not seem to concern the BJP so much now. Modi’s government and party enjoys the trust of India’s tycoons. The BJP receives more funds through electoral bonds — a form of donation to political parties — than all other Indian parties combined. The source of these funds has also been controversially made anonymous for the public by the BJP’s central government. With these and other resources, not to speak of a robust PR machinery, a strong presence in electronic media, and the support of most television channels, the BJP can afford to lose in even some of the larger states and yet remain dominant on the national stage.

Yet another factor may be the changing nature of Indian politics and narratives. Narendra Modi has made much of the BJP’s campaigning about himself. His image is everywhere and it is not often easy to tell how many votes are cast more for him as a leader, and how many for the BJP as a party. Currently no opposition party has a face and an image that can counter Modi, and there would need to be one such face on the national level to be effective. This is different on the state level, where in some regions local parties and leaders are much more popular and recognized than either Modi or the BJP.

A last factor, but perhaps one of the most crucial, is the divided opposition.

A similar disproportion between state and national level representation occurred in 1988, when another party, the Indian National Congress, held power in the central government with a record number of MPs, but ruled alone in 14 states. Moreover, while its victory in the national elections of 1984 was one the most resounding in Indian history, the party proceeded to lose six subsequent state elections in the next three years. Hindsight shows us that these events were revealing the shape of things to come. In 1989, the Congress was unable to form the government after the national elections.

This is where the parallel between now and 1988-1989 ends, however. In 1989, Congress could not retain rule because a wide coalition was formed against it; but as of 2020, such a wide coalition of opposition forces against the BJP has not been formed, and the existing opposition is not popular and powerful enough to take on Modi’s party. The above-mentioned statistics on the BJP’s presence in the states must be compared to how much power its rivals enjoy in the same field. The fact that the BJP has 31.6 percent of lawmakers across state assemblies matters less when we notice that its only rival on the national level, the Congress, has just 19.2 percent of them, the rest being scattered among various other players. It is also clear that there are regional parties that can compete with the BJP in their own territories but they are not united and strong enough to challenge Modi’s position on the national level, as of now.

In other words: At the right time and under carefully examined circumstances, a review of state elections may offer some conclusions about the national mood. But it does not seem that this time the BJP’s results in state elections are a signal that it could lose the next general polls, to be held in 2024. Any shifts that could change its standing then would arguably have to take place on the national level.