As China’s dismal human rights record attracts increasing attention abroad, critics have latched on one potential means of giving teeth to the outcry: orchestrating a boycott of the Winter Olympics set to be held in Beijing in 2022.

Last month, an international coalition of human rights organizations wrote a letter to the International Olympic Committee, asking it to “reverse its mistake in awarding Beijing the honor of hosting the Winter Olympic Games in 2022.” The activists cited China’s lengthy record of human rights violations and noted that hosting the Summer Games in 2008 did nothing to improve China’s record on that front – quite the opposite, in fact.

Beijing leveraged the 2008 Games to showcase itself as a power on the world stage, and hopes to use the 2022 Games to cement that perception. As it did in 2008, the ruling Chinese Communist Party (CCP) will use the 2022 Olympic Games for its own propaganda purposes, shoring up its legitimacy at home and abroad. Reacting to China’s successful bid for the Winter Olympics, state news agency Xinhua said, “The glory belongs to China.”

But should an international sporting event be gifting any legitimacy, much less “glory,” to the CCP, which is being accused of crimes against humanity?

The most egregious rights question is China’s mistreatment of the Turkic Muslim population (notably the native Uyghurs) in Xinjiang. After well-documented reports of detention without trial, forced sterilizations, and forced labor – all of which China officially denies – numerous governments have expressed their concerns.

Despite evidence that China’s human rights record has only worsened since it was awarded the Winter Olympics, IOC President Thomas Bach has cautioned against an Olympic boycott “because of political background or nationality.” Bach later claimed he was not referring to the 2022 Games, but his comments match the IOC’s refusal to take a stand on rights issues. There is little chance the Olympic governing body would revoke China’s right to host. (In fact, China only won the 2022 Games because there was just one other contender: Kazakhstan.)

However, a boycott of the Beijing 2022 Olympics by individual countries remains a possibility, especially as China’s image continues to deteriorate overseas.

The two most prominent previous Olympics boycotts occurred during the Cold War. In 1980, the United States led its allies to shun the Moscow Summer Olympics in protest of the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan. In 1984, the Soviet Union returned the favor by leading a boycott of the Los Angeles Summer Olympics. However, the impact was diluted in each case, because a large number of sporting powerhouses were still participating.

Things could be very different should there be an organized boycott of the 2022 Beijing Olympics.

The Winter Olympics have far fewer nations in the running for medals than the Summer Olympics – the counties that dominate the medal standings in the winter sports are heavily concentrated in the developed world. Many of them are also liberal democracies, who have been the most vocal about their concerns regarding China’s rights record. That means there’s a massive overlap between the countries that would be expected to perform well in the 2022 Games and the countries that would be most likely to take part in a boycott, if one got off the ground.

In July 2019, 22 countries signed a letter addressed to the U.N. Human Rights Council demanding that China “refrain from the arbitrary detention and restrictions on freedom of movement of Uighurs, and other Muslim and minority communities in Xinjiang.” Since then, reports on the severity of rights abuses in Xinjiang have only escalated, with some critics now unreservedly calling the campaign against the Uyghurs an attempt at genocide.

Let’s take those 22 signatories as the starting point for a potential boycott coalition. Add in the United States, which did not sign the letter (because it has withdrawn from the United Nation’s human rights body under the Trump administration) but has been actively denouncing China over Xinjiang abuses, including enacting sanctions on companies and officials involved. That gives us a list of 23 countries that have gone on record expressing serious concerns over abuses in Xinjiang, and thus could potentially join an Olympic boycott. Our list: Australia, Austria, Belgium, Canada, Denmark, Estonia, Finland, France, Germany, Iceland, Ireland, Japan, Latvia, Lithuania, Luxembourg, the Netherlands, New Zealand, Norway, Spain, Sweden, Switzerland, the U.S., and the U.K.

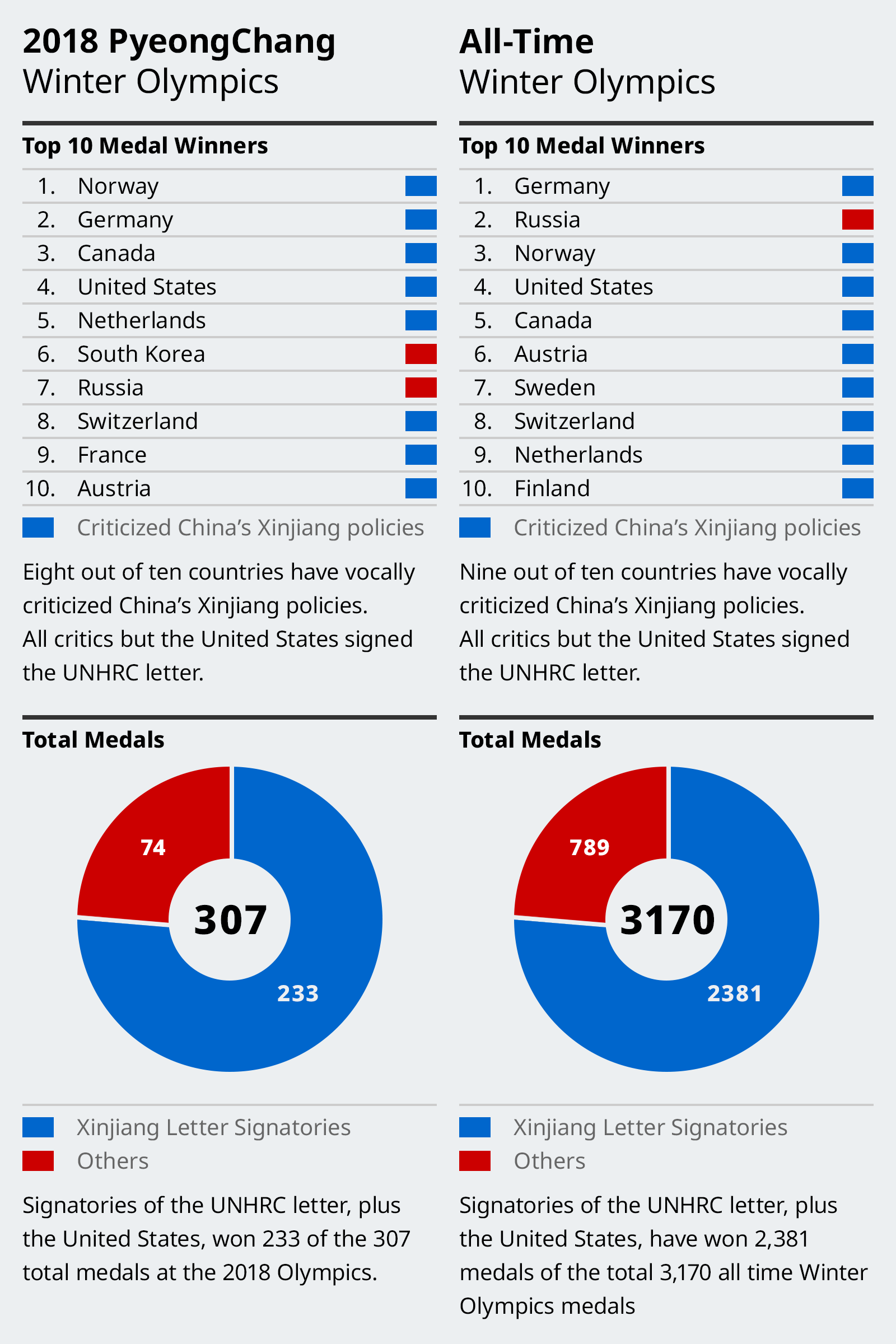

Countries on that list represented eight of the top 10 medal winners at the last Winter Olympics, the 2018 PyeongChang Games. They represent a whopping nine of the top 10 all-time Winter Olympic medal winners (with the lone exception being Russia).

Overall, the 23 countries mentioned above won 233 of the 307 total medals awarded at the 2018 Winter Olympics, nearly 76 percent. And that was no aberration; these countries combined have won more than 75 percent of Winter Olympic medals all-time.

Simply put, without these 23 countries, the Winter Olympics would be a pale imitation of itself. Based on past results, the athletes sitting out would otherwise have won roughly three-quarters of the medals.

Things become even more interesting if we posit an alternative “boycott Olympics,” as was held in Philadelphia for countries avoiding the 1980 Moscow Olympics. If the 23 countries on our list banded together to host such alternative games, athletes would face the best competition – and thus the most potential glory from a victory – not in Beijing but in the rival host.

Western liberal democracies dominate the Winter Olympics, both in terms of athletic prowess and interest in watching. If these countries put their values first and refuse to participate in an Olympics Games that at best overlooks and at worst normalizes China’s horrific treatment of the Uyghurs, their absence would entirely gut the 2022 Olympics. With athletes, viewers, and advertising dollars turning elsewhere, the Beijing Games could be made into an unprecedented flop, regardless of what impressive displays China has planned as host.

Western democracies have a chance to deny Beijing a PR victory, and instead turn China’s horrific rights record into a national embarrassment on the world stage. If the world is serious about the cry of “never again,” it’s time to start planning for that option.