In U.S.-China relations, “coordinated inauthentic behavior” is no longer just a polite description for bilateral summits, but the latest tactic in the ongoing competition for power and influence in the Indo-Pacific. On September 22, Facebook announced that it had dismantled a Chinese disinformation campaign that used false accounts and profiles to dupe unwitting individuals into consuming Chinese disinformation. Dubbed “Operation Naval Gazing” by the social media analysis firm Graphika, the network consisted of 155 accounts, 11 pages, nine groups and six Instagram accounts and attracted an audience of at least 130,000 followers. The network particularly targeted the Philippines, where it actively interfered in Philippine politics and generated millions of digital interactions by promoting politicians favorable to China, including President Rodrigo Duterte. This marks the second time that Facebook has removed disinformation networks emanating from China and heralds a new age of information warfare in the Indo-Pacific, where the United States and allies like the Philippines are uniquely vulnerable to attack.

China’s embrace of foreign influence operations marks an important evolution in its cyber statecraft. While Beijing has long embraced cyber espionage in particular as a central facet of its national security, it has historically struggled with information warfare. Yet a reassessment appears to be under way in Beijing. After witnessing Russia’s successful use of information operations, particularly in election interference, China has made a concerted effort to learn Russian disinformation tactics and adapt them to its own interests. During the 2020 Taiwan presidential election, China conducted a dedicated but ultimately unsuccessful campaign to use disinformation to sway the election and derail the reelection campaign of President Tsai Ing-wen. China has enjoyed greater success in using information operations to rebuff criticism of its handling of COVID-19. One video titled “Once upon a virus….”, contrasting China’s response to the pandemic with that of the U.S. memorably led Peter Singer to tweet: “You know that scene in Jurassic Park, the moment when the Velociraptor learns to turn the doorknob? This is it for China in online info-war.”

Operation Naval Gazing reflects this evolution in Chinese cyber operations. The earliest accounts within the network date to 2016; they focused on Taiwanese politics and advanced pro-mainland positions like espousing the benefits of reunification. However, a shift occurred in 2018 when the network broadened its activities to include a more dedicated focus on naval affairs and regional politics. In particular, the network created several Facebook portals focused on the South China Sea that trumpeted Chinese naval accomplishments and derided American activities. The network would eventually create pro-China content targeting Indonesia and the U.S., but only managed to gain significant traction in the Philippines.

The Philippines provided an ideal target for China to exercise its capabilities in foreign influence operations and is uniquely susceptible to manipulation through Facebook. Beyond being an American ally and a strategic pivot in the Indo-Pacific, the Philippines is also the most social media addicted country in the world. The Philippines tops the world in daily usage of social media, with Filipinos spending an average of roughly 4 hours per day on social media. Facebook dominates the Philippine social media landscape with 75 million active users representing 71 percent of the Philippines’ population.

This fervor for Facebook is not an accident, but an acute reflection of the informational and digital realities in the Philippines. In a country plagued by poor digital infrastructure, mobile devices have become the primary means through which Filipinos access the internet. However, mobile data plans remain expensive. To circumvent this obstacle to entry, in 2013 Facebook partnered with local carriers to offer “Free Facebook,” a plan that allowed mobile subscribers to access Facebook without using data. The result has been a meteoric rise in Facebook usage throughout the country. As Davey Alba at BuzzFeed News noted, “for many in one of the most persistently poor nations in the world, Facebook is the only way to access the internet.”

Facebook’s dominance as an information source has already made disinformation a common feature of Philippine politics. It was critical to bolstering Rodrigo Duterte’s presidential campaign in 2016. Since the election, disinformation has continued to be employed to defend Duterte’s violent war on drugs, discredit critics and undermine rival media outlets like Rappler and ABS-CBN. It is this combination of social media supremacy and undermining of traditional media outlets that made the Philippines such a welcoming target for Chinese manipulation.

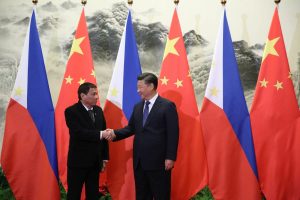

Beginning in March 2018, the Operation Naval Gazing began creating a series of Facebook accounts, pages and groups that explicitly targeted Philippine politics. The pages promoted the activities of politicians seen as sympathetic to China, including President Rodrigo Duterte, his daughter Sara Duterte-Carpio (the mayor of Davao City and a potential successor as president), and Imee Marcos (the daughter of the late dictator Ferdinand Marcos), who was elected to the Philippine Senate in 2019. While Naval Gazing’s other influence operations fizzled, its interference in the Philippines flourished. One Facebook group backing Imee Marcos attracted over 50,000 followers and, despite being active since January 2019, a group named Solid Sarah Z Duterte 2022 (referring to her potential presidential bid) made 115,000 posts and generated over 9.1 million interactions.

Operation Naval Gazing’s explicit and unequivocal interference raises difficult questions in Manila about the outsized role that social media plays in public life, and the nation’s subsequent susceptibility to disinformation. In particular, it will be fascinating to see whether President Duterte’s vocal disdain for foreign meddling extends to his allies or whether his ire is solely reserved for foreign critics. Yet, it is a mistake to view China’s activities only through the lens of Philippine politics. Facebook’s exposure of Chinese influence operations illustrates a larger strategic evolution and constitutes a direct challenge to both the U.S.-Philippine alliance and American defense prerogatives throughout the Indo-Pacific.

The launch of Naval Gazing’s Philippine campaign in March 2018 was not tied Philippine politics but was initiated immediately after U.S. Secretary of State Mike Pompeo reaffirmed American defense commitments to the Philippines in the South China Sea. On Facebook the various profiles, page, and groups not only promoted politicians aligned with China, but unambiguously campaigned for the Philippines to realign itself with China. For example, amid the COVID-19 outbreak Naval Gazing defended China’s handling of the pandemic, celebrated medical aid from Beijing despite its dubious benefits and praised China for its generosity in offering as-yet non-existent vaccines to the Philippines. The South China Sea featured prominently throughout these efforts, including praise for Duterte after he stated that China was “in possession” of the South China Sea. Taken collectively these elements demonstrate a concerted campaign to weaponize social media against the U.S.-Philippine alliance.

Having failed to either bully the Philippines into obedience or buy its acquiescence, China has now embraced political interference as a means of decoupling the Philippines from the U.S. Specifically, China has identified the political discord within the U.S.-Philippine alliance as the partnership’s greatest vulnerability and recognized social media as the ideal tool with which to inflame this divide and achieve its strategic objectives. Importantly, while the Philippines’ fondness for Facebook makes it particularly susceptible to foreign influence operations, the underlying conditions of intra-alliance tension that made the campaign dangerous color security partnerships throughout the region. Rather than being a brief foray into active measures, Operation Naval Gazing evinces a wider strategic embrace of foreign influence operations by China that could begin to erode the U.S. alliance system.

In the face of a similar threat from Russian active measures, NATO has pioneered a collaborative approach to cyber defense and created innovative programs like the Cooperative Cyber Defense Center of Excellence and a handbook on Russian information operations to help member-states detect and defeat foreign influence operations. It is essential that similar programs be developed and implemented in the Indo-Pacific as well. Proactive engagement with partners like the Philippines to develop capabilities to resist malicious cyber campaigns are essential to seizing the initiative in the information environment and must be enshrined as a strategic priority.

Expanding existing defense cooperation initiatives and training programs to include cybersecurity is an essential first step but combating disinformation cannot succeed as a military undertaking alone. Instead, as the U.S. adopts a more competitive posture in its cyber diplomacy, cooperative engagement with partners like the Philippines should be a focal point of these undertakings and provide a framework for collaborative action not just with partner states but also between American agencies as well. Indeed, to mitigate underlying conditions and societal factors like the Philippines’ Facebook’s addiction it is necessary to embrace an interdisciplinary and inter-departmental framework. Ultimately, a wide range of policy resources and expertise is required to implement programs like infrastructure development, media literacy training and cybersecurity education that are necessary to build community resilience against foreign manipulation.

At its heart, Operation Naval Gazing is a warning siren as to whether Tokyo, Seoul, Canberra, Manila and especially Washington are willing to take proactive measures to defend their information environments. If not, they will again risk being caught flatfooted as a foreign actor learns to use social media to undermine their collective security.

Gregory Winger is an assistant professor of political science and fellow at the Center for Cyber Strategy and Policy (CCSP) at the University of Cincinnati. He is also a fellow with the National Asia Research Program. Winger has written on the U.S.-Philippine alliance for War on the Rocks and the Philippine Star.