As the United States and much of the world face down the spiraling COVID-19 crisis, the functioning of the U.S. postal system has temporarily taken center stage in the news cycle. Questions over mail-in ballots and the sufficiency of U.S. Postal Service’s infrastructure to face escalating election season demands have percolated through Congress and the media, while threats of downsizing and funding cuts loom large over an already-struggling system.

This is not the first time a postal system has struggled in the face of a global pandemic. The last time, the struggle was on horseback, when another deadly pathogen brought an impressive postal system to a halt.

Early postal systems were in no small part responsible for the genesis of international networks of people, culture, and commerce that we take for granted as part of 21st century life. The first formalized postal relay was generated in the first millennium BCE by the Persian Emperor Cyrus the Great, on the heels of the spread of mounted horseback riding in interior Eurasia. More than 100 stations linked the capital of Susa, in present-day Iran, with the edges of Anatolia in Sardis. As other empires rose and fell, new horse postal systems emerged – in China during the Han and Tang Dynasties, and in places such as Egypt, Syria, France, and Italy during the Middle Ages. In the United States, as well, horses helped form the country’s first postal infrastructure. Before the railroads, colonial mail on the eastern seaboard was delivered by horse post, while the short-lived Pony Express underwrote efforts to connect newly accessioned California with settlements in St. Louis across a territory of more than 3,000 km.

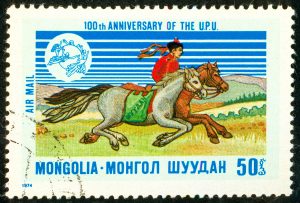

The most famous horse-based postal relay came with the rise of the great Mongol Empire in the 13th century, which created a system of postal outposts spanning a distance of roughly 60,000 km. Transit across the Mongol Post played a central role in maintaining coherence across the massive and loosely connected empire. Across the postal roads moved messengers, diplomats, and traders – including Marco Polo, who would famously narrate his travels in “The Travels of Marco Polo.” These institutionalized networks helped ruling dynasties regulate and facilitate trade and maintain both communication and authority across vast continental distances.

A passport or “paiza” carried by messengers along Mongolia’s postal relay system during the 14th century, now in the collections at the National Museum of Mongolia. Photo credit: National Museum of Mongolia

In a curious echo of our present day, the hyperconnectivity generated by the Mongol Empire (and its postal relay) carried with it the seeds of disaster. As the 14th century approached its midpoint, the bubonic plague (Yersinia pestis) – native to the Eurasian steppes – made the jump from animals to humans. The guilty party might have been marmots, which remain both a popular food in steppe cultures and a pernicious reservoir for the plague to this day. As the plague spread westward along the trade routes linking Mongolia with Central Asia and beyond, the destruction it wrought caused political turmoil that ultimately saw the postal roads ceasing to function in the late 1340s.

While the pandemic helped to end the Mongol Empire’s relay, a horse-based postal system continued to serve the remote regions of Mongolia long into the 20th century. Bat-Erdene Bayarmagnai, a native of Khuvsgul province in northern Mongolia, recalls how his grandparents worked for years on one section of the country’s pony express in the years following the Communist Revolution during the 1930s and 1940s. In lieu of paying national taxes, the family was required to keep a team of horses saddled and at the ready. Other families were responsible for maintaining food and lodging for those using the postal road. The arrival of the mail – day or night – to their yurt would require one of the grandparents to swiftly mount their horse and deliver the post to the next station, nearly 30 km away. “Some days, there was pretty heavy traffic, even in the middle of the night,” Bat-Erdene says.

Despite its length, this ride was accomplished in around two hours. Once in a while, an important letter might arrive that needed special handling – in this case, the visiting courier would commandeer horses for his own use, traveling to the next station accompanied by the station attendant to protect against injury or wolves.

Map showing the location of the postal stations in Bat-Erdene’s family stretch of the Mongolian postal network, each spaced roughly 30 km apart.

Ultimately, the increasing accessibility of motorized vehicles would spell the end of horse-based postal delivery in Mongolia. Throughout the 1940s, horses remained the main form of transport in the region (Mongolia even fought a famous cavalry battle with Chinese forces at Baitag Bogd along their southwestern border in 1947). However, the post-war intervention of the Soviet Union brought more access to cars and obviated the need for mounted riders. Nonetheless, the grassland nation, which has one of the lowest population densities in the world, has remained committed to rural postal delivery — the Mongolian postal system recently made headlines for its partnership with “what3words,” a GPS-based system that, in principle, allows any location to become a deliverable mail address — including the mobile camps of herders living in remote regions.

Today, there are no more horses carrying the post in the United States, either – other than the annual Pony Express reenactment ride that remains popular among horse and history buffs (appropriately enough, this ride itself was also canceled in 2020 due to pandemic-related concerns). For rural Americans, especially Indigenous peoples living far from urban centers, the USPS is a crucial link to goods, services, and election ballots. The challenges posed by COVID-19 make these services more important than ever to the functioning of democratic governance, public health, and the economy. And, while many things have changed since the time of Genghis Khan, it is hard not to see the declining health of the USPS in the face of a global pandemic as a similarly dire omen of eroding infrastructure – and eroding authority – for the United States on the world stage.

William Taylor is curator of archaeology and assistant professor of anthropology at the University Colorado-Boulder.