Vietnam’s prime minister has defended his nation’s exchange rate policy, arguing that it is not aimed at boosting its exports and asking that U.S. President Donald Trump come to “a more objective assessment of the reality in Vietnam.”

On October 2, the U.S government announced that it was opening an investigation into whether Vietnam has been purposefully suppressing the value of the dong. According to a statement from the office of the U.S. Trade Representative (USTR), Washington will “investigate Vietnam’s acts, policies, and practices that may contribute to the undervaluation of its currency and the resultant harm caused to U.S. commerce.”

According to USTR, the probe was launched “at the direction of President Donald J. Trump,” who has shown an obsessive fixation toward countries that have large trade surpluses with the U.S. At the same time, Washington also announced a second investigation into Vietnam’s use of timber that has been illegally harvested or traded.

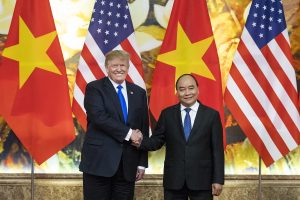

In a meeting in Hanoi on October 26, Prime Minister Nguyen Xuan Phuc told Adam Boehler, head of the U.S. International Development Finance Corporation, that the U.S. should not leap to any rash conclusions. “If the dong is devalued, it will seriously hurt the economy,” Phuc said. “Vietnam is not using exchange rate policy to create competitive advantage in international trade.”

In August, the U.S. Department of Treasury concluded that Vietnam had manipulated its currency in at least one case involving the export of light vehicle tires. Treasury informed the U.S. Commerce Department that that Vietnam’s currency was undervalued in 2019 by around 4.7 percent against the dollar due in part to government intervention: that is, the government was artificially holding down the value of Vietnam’s currency in order to increase the competitiveness of its exports.

This year, Vietnam has had the fourth-highest trade surplus with the U.S., its largest export market, after China, Mexico and Switzerland. According to Vietnamese figures, the deficit stood at $44.3 billion as of September, up from $33.96 billion in the same period last year. Much of the increase can be put down to the Trump administration’s trade war with China, which has prompted a number of international manufacturers to move their operations to Vietnam.

The investigation, which has been undertaken under Section 301 of the 1974 Trade Act, could conceivably result in the imposition of tariffs on Vietnam’s exports to the U.S. However, harsh punishments are unlikely for several reasons. For one thing, according to one analysis, Vietnam’s currency is actually overvalued on a real effective exchange rate basis, both in absolute terms and relative to the 10-year median.

Moreover, as I wrote following the initial American announcement of the probe, the U.S. has good reasons to keep relations with Vietnam on an even keel. In recent years, the two nations have seen a steady strategic convergence, due to their common concern about Chinese ambitions in the region, particularly in the South China Sea. Pushing the investigation too hard, or erecting harsh tariffs against Hanoi, would likely to be counterproductive to this broader strategic goal.

In any case, currency investigations usually take a long time, and after the result of next week’s U.S. presidential election, it remains to be seen whether either the lame-duck Trump administration, or a putative Biden administration, will have the appetite to pressure a strategic ally over a relatively minor issue.