South Korea confirmed its first case of COVID-19 on January 20 and since then has received international acclaim for its response to the pandemic, which relies on extensive testing, free medical treatment, and sophisticated technology. South Korean officials also used GIS technology and government-created apps to follow the spread of the virus, helping the country stem the spread of the outbreak before cases got out of hand. Cases peaked on March 3 with 803 daily cases, but dropped to under 100 a month later. While South Korea experienced a mild second wave in August, when daily cases were in the 200s and 300s, daily numbers have recently declined to the double-digits again.

However, not everyone has been content with the government’s handling of the coronavirus pandemic. Many medical professionals went on strike, protesting the government’s decision to recruit additional medical students rather than raise wages. Additionally, South Korea’s government often publicly announces those who test positive, which critics cite as an infringement of individual privacy and an invitation for public bullying. Similarly, a recent survey of South Koreans found that 40 percent believe that the harsh COVID-imposed restrictions hurt their mental health. Some groups, such as the controversial Sarang Jeil Church, believed to be responsible for thousands of COVID-19 cases in South Korea, have taken part in anti-government rallies.

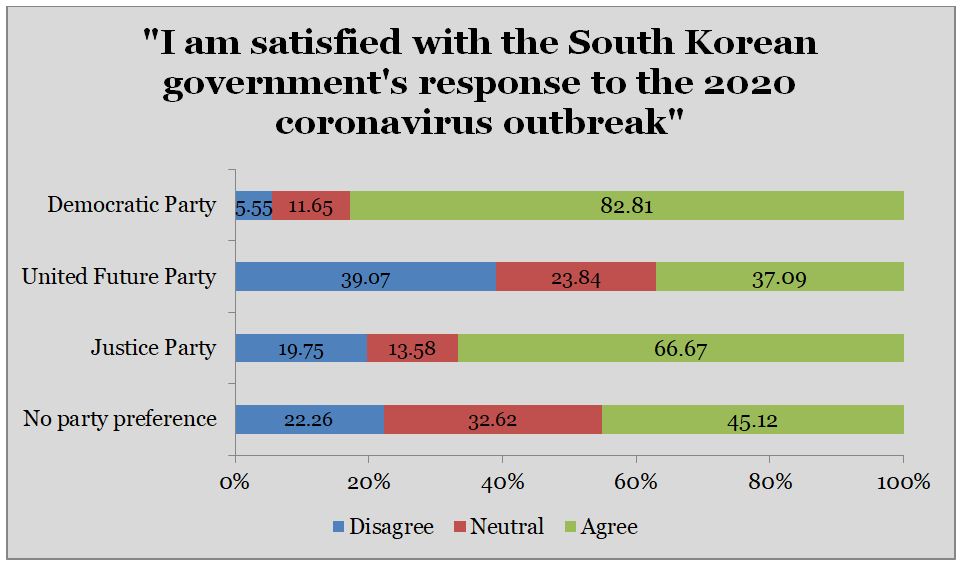

In April, South Korea conducted National Assembly elections, providing a clear example of how to conduct a safe election during a pandemic. The result was the highest turnout for legislative elections in nearly 30 years and a clear victory for President Moon Jae-in’s Democratic Party. Yet, survey results showed views on COVID-19 largely fell along partisan lines, with supporters of the Democratic Party largely viewing the government’s response in positive terms and supporters of the conservative United Future Party (recently rebranded as the People Power Party) overwhelmingly opposed.

Did this partisan lens endure beyond the election cycle?

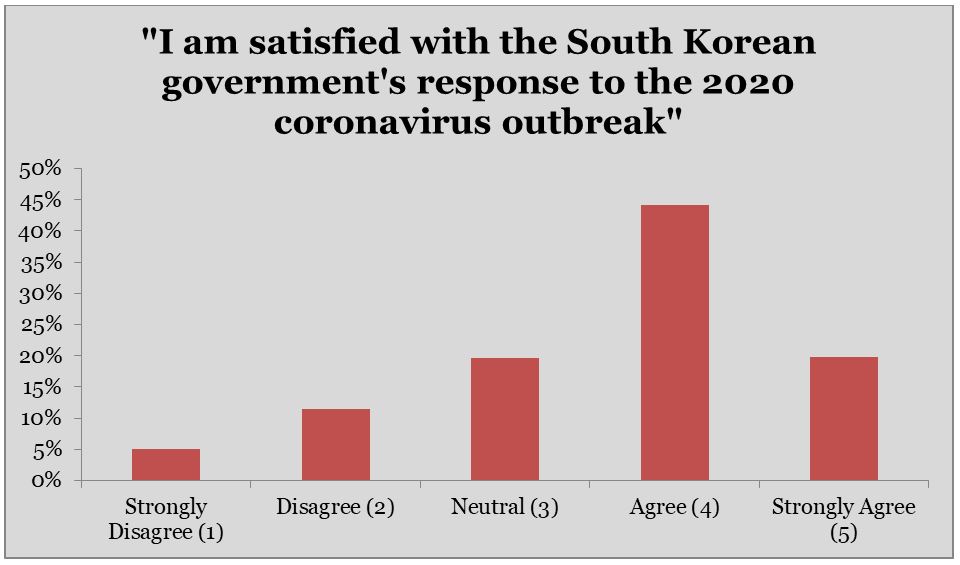

To address this question, we surveyed 1,200 South Koreans from September 9-18, via a web survey administered by Macromill Embrain, using quota sampling by region and gender. We asked each respondent to evaluate the statement “I am satisfied with the South Korean government’s response to the 2020 coronavirus outbreak” on a five-point Likert scale from strongly disagree to strongly agree. During the time of the survey, the number of daily cases in South Korea remained fairly steady, ranging from just over 100 to nearly 180 cases per day.

The figure below shows the summary results. A broad majority of respondents agreed (44.08 percent) or strongly agreed (19.75 percent) that they were satisfied with the government’s COVID-19 response. Less than one-fifth of respondents strongly disagreed (5.08 percent) or disagreed (11.50 percent) with the government’s handling of the outbreak.

Interestingly, we ran the same survey question in March 2020 and the results were very different – only about 44 percent of respondents supported the government’s response while approximately 36 percent viewed it negatively. This shift could be a result of changing views on the response, perhaps as Koreans see how other countries like the United States struggled to limit cases, or due to witnessing the global death toll surpass 1 million, or simply due to the end of an election cycle and partisan campaigning.

We then broke down the data by political party to determine if there is a partisan perception of South Korea’s coronavirus response, combining “strongly disagree” with “disagree” and “strongly agree” with “agree” for simplicity. While there is widespread support for the government’s COVID-19 response, disaggregating the data by political party shows continued variation. Approximately four-fifths (82.81 percent) of the respondents from the Democratic Party, the current party in charge of the South Korean government, supported the government’s approach to the pandemic. Similarly, there is strong support from the more progressive Justice Party, with two-thirds (66.67 percent) of respondents viewing the government’s COVID-19 response as successful. Members of the conservative opposition United Future Party/People Power Party (37.09 percent) and those without a party preference (45.12 percent) were less likely to support the government’s COVID-19 response, but still were unlikely to disapprove of it. Moreover, support for the government’s responses have increased across all groups compared to March survey data, with Democratic Party support increasing by 10.08 percent, United Future Party by 28.54 percent, Justice Party by 10.41 percent and those without a party identification by 17.2 percent.

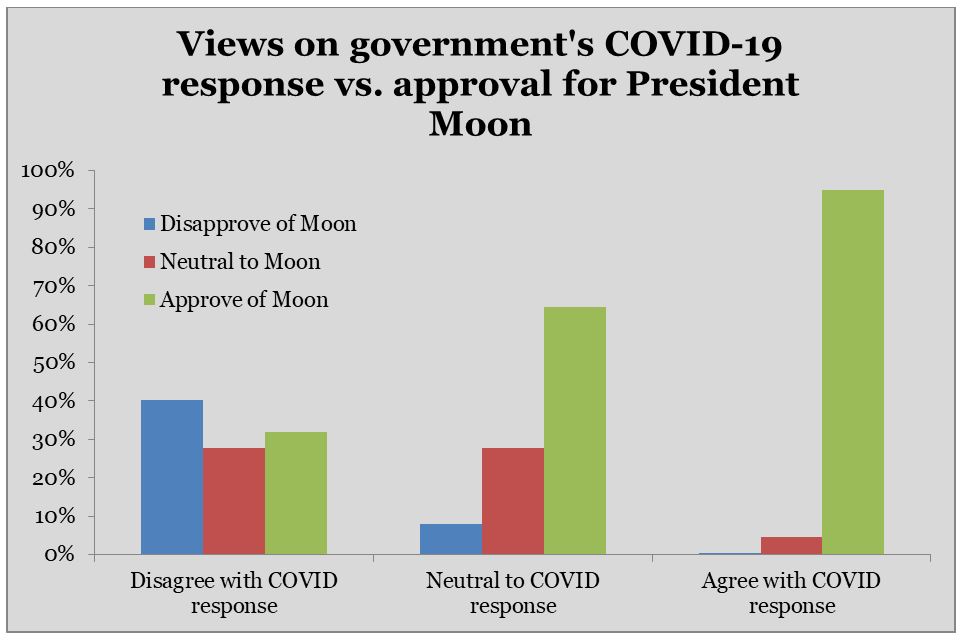

Lastly, we wanted to compare how people perceived the government’s COVID-19 response in relation to how they rated the performance of President Moon. Unsurprisingly, support for Moon and the government’s COVID-19 response mirror each other; 95.05 percent of respondents who agree with the government’s pandemic policies also approve of Moon’s performance. Similarly, 64 percent of respondents who were neutral toward the government’s COVID-19 response approved of Moon’s performance, while a plurality (40.24 percent) of those who disagreed with the pandemic response also disapproved of Moon’s performance.

The results here suggest that despite continued partisan differences on the appropriateness of the government’s COVID-19 response, increasingly South Koreans view the response favorably. However, it remains unclear whether this is motivated by comparisons between South Korea and COVID-19 responses elsewhere and the international praise for their country’s response or their specific experiences with testing and safety precautions. Likewise, it is unclear what South Koreans see as an acceptable rates of cases and whether another wave would dampen this support.

Timothy S. Rich is an associate professor of political science at Western Kentucky University and director of the International Public Opinion Lab (IPOL). His research focuses on public opinion and electoral politics, with a focus on East Asian democracies.

Madelynn Einhorn is an honors undergraduate researcher at Western Kentucky University, majoring in Political Science and Economics.

Andi Dahmer is a 2018 Harry S. Truman Scholar and recent graduate of Western Kentucky University.

Isabel Eliassen is an Honors undergraduate researcher at Western Kentucky University majoring in International Affairs, Chinese, and Linguistics.