Next week’s U.S. presidential election is shaping up as a hugely consequential event for both American domestic politics and Asia’s security order. As the U.S. is a critical and burgeoning diplomatic partner of Vietnam, the election outcome will undoubtedly have an impact on U.S.-Vietnam relations. But what will Vietnamese leaders look for from the next U.S. administration?

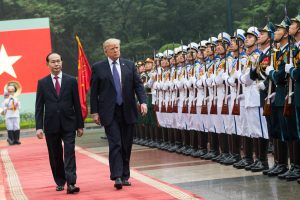

Under the Trump administration, U.S.-Vietnam relations continued their upward trajectory. The U.S. remained Vietnam’s number one export market and more U.S. businesses considered moving production lines and supply chains to Vietnam in order to avoid trade war tariffs. Security cooperation has seen a significant expansion. Other than port visits by U.S. warships and aircraft carriers, the U.S. also provided security assistance to improve Vietnam’s maritime domain awareness capacity through training and equipment acquisition. Vietnam also participated in the Rim of the Pacific (RIMPAC) exercise for the first time in 2018. Increased U.S. support is welcome in the context of the South China Sea, where Vietnam is locked in territorial and maritime disputes with China. Vietnamese leaders also welcome non-military initiatives to strengthen U.S. engagement with the region, including the Blue Dot Network for quality and sustainable infrastructure and the U.S.-Mekong Partnership to assist Mekong riparian countries in preparing for drought and climate change.

That said, Trump’s first term represented a mixed blessing for U.S.-Vietnam relations. Despite its status as a rising security partner, Vietnam has not been immune to Trump’s trade tirades, due to its large trade surplus with the U.S. and the concomitant accusations of currency manipulation by Hanoi. While Trump’s tough stance on China certainly resonates with the Vietnamese public, Vietnamese leaders have taken a more measured attitude. For Vietnam, a bitter rivalry between its two critical partners is a worrying sign, given that its leaders tend to prefer a “not too hot, not too cold” balance in U.S.-China relations, so they can leverage the inherent tensions between two superpowers without those tensions becoming a source of serious instability. Trump’s disdain for multilateralism and his quarrels with traditional allies over burden-sharing and trade disputes aggravate long-held concerns about U.S. retrenchment in the face of China’s growing influence.

An exclusive focus on security won’t work

In light of China’s growing power and assertiveness, the U.S. continues to be one of the most critical partners of Vietnam, and Hanoi hopes to maintain the upward trajectory of bilateral relations. But Vietnam hopes that the next U.S. administration offers a more nuanced form of engagement balanced toward stronger cooperation in non-military fields. Washington’s Indo-Pacific Strategy is often viewed with skepticism in the region due to its security-focused agenda and its characterization of Beijing as an unalloyed threat to the region. In this respect, the Vietnamese government is no exception.

China is Vietnam’s largest trade partner and currently enjoys a huge trade surplus due to Vietnam’s heavy reliance on China’s equipment and components that go into the manufacture of its own exports. Shared culture and history, as well as similarities in political systems and ideologies, have also contributed to China’s importance in Vietnam’s foreign policy. These robust ties mean Vietnam can’t afford to take a simple binary view of China, despite recurrent tensions in the South China Sea. Furthermore, economic growth and development remain the Vietnamese leaders’ top priority. Instead of an open balancing approach vis-à-vis China, Vietnam hedges its bets by diversifying its foreign relations and expanding cooperation with other external powers, with a strong emphasis on economic cooperation.

Other Southeast Asian states have taken a similar approach. They regard China as an indispensable partner for the region’s development and prosperity, acknowledging that Southeast Asian fortunes are tied to China’s continued stability and growth. Simultaneously, lack of trust and anxiety caused by China’s rising economic and military power have also driven Southeast Asian states to pursue different forms of hedging in a bid to maintain their strategic autonomy.

A more multidimensional engagement

While regularized Freedom of Navigation Operations (FONOPs) and Washington’s more explicit stance on the South China Sea disputes are both welcome steps, they are insufficient to anchor U.S. influence. Instead, a more multidimensional engagement, in which the U.S. offers credible incentives in non-military fields to meet Vietnam’s urgent needs, will go much further in strengthening bilateral relations.

Regarding China, Vietnam expects the next U.S. administration to preserve certain elements of its current China policy. These include publicly speaking out against China’s incremental encroachment in the South China Sea, and a continuation of FONOPs and enhanced maritime security cooperation with Vietnam, particularly maritime domain awareness and maritime law enforcement. Simultaneously, Vietnam would prefer the U.S.-China rivalry to de-intensify. Hanoi favors a balanced dose of competition and cooperation between Beijing and Washington and does not want a military conflict between two great powers erupting in the South China Sea.

Economically, Vietnam hopes to see the U.S. rejoin the Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership (CPTPP), the successor of the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP), from which the U.S. withdrew in the first few days of the Trump administration. American withdrawal from TPP dealt a hard blow to Vietnam, which was among the nations that stood to benefit the most from the mega trade deal. More robust economic engagement with the U.S. will help alleviate Vietnam’s reliance on trade with China, thus providing greater strategic autonomy and resilience against economic coercion. If joining CPTPP proves to be too controversial for U.S. voters, other forms of economic engagement should be considered.

Like other Southeast Asian states, the lack of quality infrastructure has a limiting effect on Vietnam’s economic growth. China and Japan are currently the two big players in infrastructure, each having invested hundreds of billion dollars. The U.S. has also joined the game with the Blue Dot Network, a multilateral initiative formed jointly with Japan and Australia, which aims to certify infrastructure projects that meet financial transparency and environmental sustainability standards. Furthermore, the U.S. overhauled its Overseas Private Investment Corporation (OPIC) into a new International Development Finance Corporation (IDFC) with improved financing capabilities, increasing its total funding portfolio ceiling to $60 billion. These are meaningful steps, but the U.S. will compete more effectively if it increases funding and works closely with Japan, the region’s leading infrastructure developer. The U.S. recently allocated $1.45 million in technical assistance to help Ho Chi Minh City develop a smart city operation center. Given that other cities in Vietnam are also facing traffic congestion or flooding, this type of cooperation is a promising avenue for future collaboration.

Finally, Vietnam hopes the next U.S. administration will continue its support for Mekong riparian countries. Early this year, Vietnam experienced a severe drought due to saltwater intrusion and decreased downstream water flow. China’s dam-building projects in Mekong’s upstream stretch have been identified as a major factor behind the more intense and frequent droughts. The U.S. has traditionally assisted Mekong riparian states through the Lower Mekong Initiative, recently expanded into the U.S.-Mekong Partnership, which aims to support good governance, transparency, connectivity and sustainable development. The sustained American support for this initiative is critical for Vietnam, whether to pressure China to be more transparent about its upstream dam-building activities and their impact on downstream countries, or help farmers prepare for adverse effects of climate change and drought.

Constrained capabilities

In addition to diversifying its engagement with Vietnam, the U.S. government should consider widening bilateral cooperation to a multilateral framework to anchor U.S. influence in the region. Other Southeast Asian states also share similar concerns to Vietnam regarding economic growth, infrastructure development and China’s role in the region. By recalibrating its engagement to fit Southeast Asian needs, the U.S. would be better positioned to compete with China. In this direction, ASEAN continues to serve as an indispensable platform for the broadening of cooperation. Furthermore, Vietnam and other regional states can consider non-traditional security cooperation with different groupings, such as the Quad. The recent Quad ministerial meeting showed a consensus among members about issues critical to ASEAN, including support for ASEAN-centrality and the ASEAN-led regional architecture, cooperation on maritime security and the provision of quality infrastructure to the region.

Widening cooperation from a bilateral to a multilateral framework also takes into account the reality of declining American power and influence in the region. The 46th president will preside over a starkly different America, weakened by the COVID-19 pandemic, an economic recession and domestic social divisions. Consequently, national renewal will be the top priority, and the U.S. will have to rely more on its allies and partners to support and preserve the Asian security architecture. Nevertheless, to what extent these expectations can become a reality depends on not only the election outcome but also the formation of the U.S. House of Representatives and the Senate. While U.S.-Vietnam relations are likely to continue on their upward trajectory, how Washington’s constrained capabilities affect cooperation remains an open question.

Hanh Nguyen received her M.A. in International Relations at International Christian University, Tokyo. Her research interest includes Vietnam’s foreign policy and US-China relations. She was a fellow under the Japanese Grant Aid for Human Resource Development Scholarship (JDS). She has written for the Pacific Forum, 9DashLine, Geopolitical Monitor and the East Asia Security Centre.