In 2002, in an interview with the BBC, Ouyang Ziyuan, the chief designer of China’s Lunar Exploration Program (CLEP) stated “one of our goals is to bring lunar samples back to China for analysis. We are interested in the minerals on the moon. We will prepare an unmanned spacecraft to do this.” Eighteen years later, the Chang’e 5 is scheduled to launch next week for a lunar sample return mission.

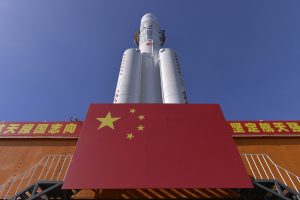

The aim of the mission is to land on the lunar near side, collect about 2 kilograms of lunar samples, and return them to China for scientific analysis. The landing site for the mission has been selected near the Mons Rümker, an isolated volcanic formation located in the Oceanus Procellarum region on the moon’s near side. This landing site has been chosen by China because it has remained unexplored, either by human or robotic missions. In comparison to the Chang’e 4 mission, which is studying the lunar far side and active even now, more than a year into its planned mission time, the Chang’e 5 is planned for one lunar day (14 Earth days). The rocket that will launch the Chang’e 5 mission, the Long March 5B, first successfully launched into orbit on May 5, 2020.

The deputy chief designer of CLEP, Yu Dengyun, highlighted the significance of the Chang’e 5:

The Chang’e-5 probe is expected to realize lunar sample collection, takeoff from the moon, rendezvous and docking on lunar orbit and high-speed reentry into the Earth’s atmosphere, marking breakthroughs in China’s aerospace history… China is conducting a further verification study for the research and development of space station and the manned lunar mission, and it plans to set up an unmanned lunar research station for manned landings on the moon.

The Chang’e 5 will accomplish several firsts for China to include, amongst others, a lunar ascender and returner. The complexity of the Chang’e 5 mission was highlighted by its deputy chief designer, Peng Jing, from the China Academy of Space Technology. Peng explained that:

The probe, to be launched by the end of this year, will enter the Earth-moon transfer orbit. It will slow near the moon to enter the lunar orbit and descend and land on a pre-selected area for ground research work, including collecting lunar samples… After finishing its work on the moon, the ascender will rise from the lunar surface for rendezvous and docking with the orbiter flying around the moon. Then the returner will fly back to Earth via the Earth-moon transfer orbit, reenter the atmosphere and land at the Siziwang Banner (County) of Inner Mongolia Autonomous Region.

As per the China National Space Administration, the Chang’e 5 lunar sample return mission will be followed by the Chang’e 6 sample return mission from the lunar South Pole (planned for 2024) and the Chang’e 7 comprehensive survey mission of the composition of the lunar South Pole (2030). The Chang’e 8 mission will lay the groundwork for China’s lunar research base on the moon by 2036. Wu Weiren, the chief designer of CLEP specified that China’s lunar missions are aimed at permanent settlement on the lunar surface.

Strategic Implications of Chang’e 5

This is not the first time lunar samples have been returned to Earth. The Apollo 11 mission accomplished that feat 51 years ago when Neil Armstrong and Buzz Aldrin brought back with them 22 kilograms of lunar rocks (the Apollo missions had brought back 382 kilograms by the time the program ended in 1972). China’s lunar samples will be from lunar sites different from that of Apollo, be it from near the Mons Rümker, or the lunar South Pole (if China succeeds in its lunar South Pole sample return mission by 2024). The South Pole is believed to be rich in resources like water-ice, critical for life support and rocket fuel. The extended periods of sunlight (200 Earth days) near the Shackleton Crater of the lunar South Pole will provide an ideal location for a lunar base, allowing for power generation and for sustaining human life.

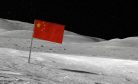

Ouyang Ziyuan, father of the Chang’e missions and founder of China’s lunar program said it best: “the moon could serve as a new and tremendous supplier of energy and resources for human beings…this is crucial to sustainable development of human beings on Earth…Whoever first conquers the moon will benefit first.”

The strategic significance of the moon as a pit stop to develop deep space faring capacities, to include dominance and access to cislunar space (the space between Earth and the moon), has been recognized in China’s white paper on space. The 2016 white paper made clear that “the Chinese government takes the space industry as an important part of the nation’s overall development strategy, and adheres to the principle of exploration and utilization [emphasis added] of outer space for peaceful purposes…to explore the vast cosmos, develop the space industry and build China into a space power is a dream we pursue unremittingly.”

On the occasion of China’s Space Day, April 24, 2019, President Xi Jinping wrote a letter to senior space scientists in which he encouraged them to “strive to strengthen and expand our space exploration and make our country a great space power as soon as possible.” China aspires to become the lead space faring nation by 2049, in time for its centennial celebration of the establishment of the People’s Republic.

For Xi, space is critical to enhance the long term rejuvenation of the Chinese nation. He directed the establishment of a separate military service for space, the People’s Liberation Army Strategic Support Force (PLASSF); the development of China’s counter-space capacities to include ASAT, jamming, and dazzling; as well as directing all private space startups to work under his civil-military fusion guidance.

In June 2019, China launched its first sea-borne rocket launch from the Yellow Sea called the Long March 11. This gave China the capability for mobile launches. This year in June, China successfully completed the final launch of its independent navigation system, the BeiDou, as well as independently launched its first Mars mission.

The geopolitical implications of China’s developing space capacities, especially regarding the moon, are clear to observers of great power behavior. Under the direction of Xi and senior scientists, China is steadily developing the overall space capacity that marks a great power: an independent launch capacity, reusability, a private space sector, investment in future capabilities (like artificial intelligence and the combination of 3D printing, low earth orbit satellites, and 5G) ASAT weapons, independent military service, independent Global Positioning System, and enhanced civilian space capacity. For Xi, the message is clear. If China is to become the global lead actor, investing in long-term space capacity is a priority. It is in this context that the strategic significance of the moon is often highlighted as a critical component of China’s overall space power.

For China, the moon has intrinsic value, and the country plans to spend the next 20 years building the strategic hardware to establish cislunar presence and capacity. In China’s strategic imagination, the moon is similar to the disputed islands in the South China Sea (SCS), the possession of whose resources will not only augment China’s space capacity but result in its lead position in deep space. Senior space officials from the PLASSF highlight the need for continuous development of capacity for dominating the Earth-moon space because in their perspective, whoever dominates this strategic area will control the access lines to deep space. Bao Weimin, director of science and technology, at the China Aerospace Science and Technology Corporation also referred to the economic prospects of the moon in 2019, pledging to establish a $10 trillion Earth-moon space economic zone by 2050.

It is in light of this strategic narrative that Chang’e 5 and the subsequent lunar and other space missions take on added strategic significance. These missions are not just about scientific exploration of the lunar surface and beyond, but about developing Chinese space power and the attractiveness of its space vision, with a focus on the moon as its priority. China’s single-party dominated space program has the ability to commit to long-term missions, unlike the U.S., where space mission goals flip-flop depending on the public mood and with every change in presidential administration, creating deep-seated uncertainty, including for international partnerships like the Artemis Accords.

Going forward, we should see more and more countries join in on China’s Belt and Road-driven space initiatives including its plans for an international lunar development vision. In a world where space is fast becoming a critical part of our infrastructure, the country with the most attractive long-term vision will win in the strategic long game for power and influence.