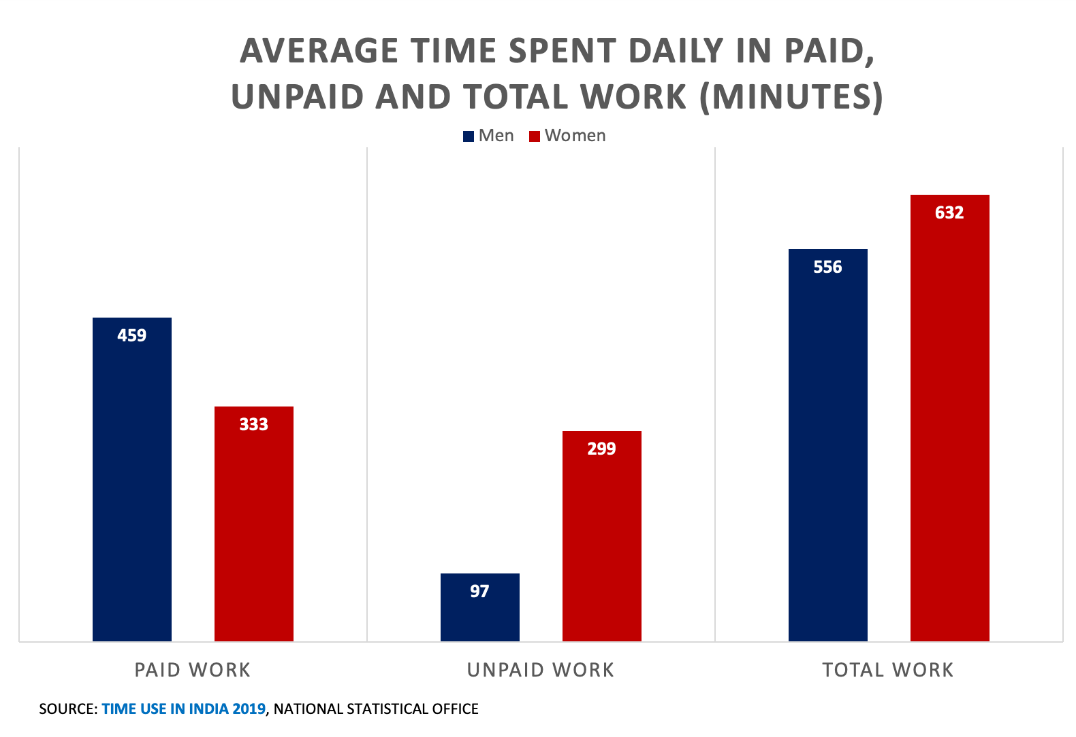

India’s first-ever time use survey finds that women continue to do over one more hour of work every day than men. The report highlights the rampant “time poverty” experienced by women when it comes to their participation in paid work. While Indian men spend 80 percent of their working hours on paid work, women spend nearly 84 percent of their working hours on unpaid labor.

Figure: Bansari Kamdar. Data: MOSPI

One of the repercussions of their unpaid work burden is their lack of participation in paid work. Indian women’s participation in paid employment is much lower than their male counterparts. Only 21.8 percent of women aged 15-59 years were engaged in paid work in comparison to nearly 70.9 percent of the men. However, if we were to take into account both paid and unpaid work, women’s participation reaches 85 percent — men’s is just 73 percent.

According to the World Bank, female labor force participation in India has fallen by nearly 30 percent in the last 20 years. In other words, one in three women in India have left the workforce. Globally, only Yemen, Iraq, Jordan, Syria, Algeria, Iran, and the West Bank and Gaza, have worse female labor force participation.

When Indian women do participate in paid employment, they spend nearly two hours less on paid work. On the other end, when it comes to housework, on average, Indian women spent 243 minutes a day on domestic chores and household work, almost 10 times the 25 minutes that the average Indian man did in 2019.

Globally, while unpaid domestic work by women is valued at nearly 13 percent of the total economy, in India, women’s unpaid domestic work is estimated to be valued at almost 40 percent of its current GDP. While women carry the Indian economy on their backs through their backbreaking domestic work and care work, it often goes unaccounted for as it is not considered productive labor.

This devaluation of women’s work and its exclusion has led to the reinforcement of the gendered division of paid and unpaid labor, leaving women without wages and little bargaining power in the household and allowing the vicious circle to continue where men, economy, and country prosper at their expense.

Figure: Bansari Kamdar. Data: MOSPI

Women were hit much harder by the pandemic and the looming recession, according to a discussion paper by Ashwani Deshapande. She finds that four out of every 10 women who were working during the last year lost their jobs during the lockdown. At the same time, the COVID-19 pandemic has disproportionately increased the time women spend on family responsibilities, by nearly 30 percent in India, according to one estimate.

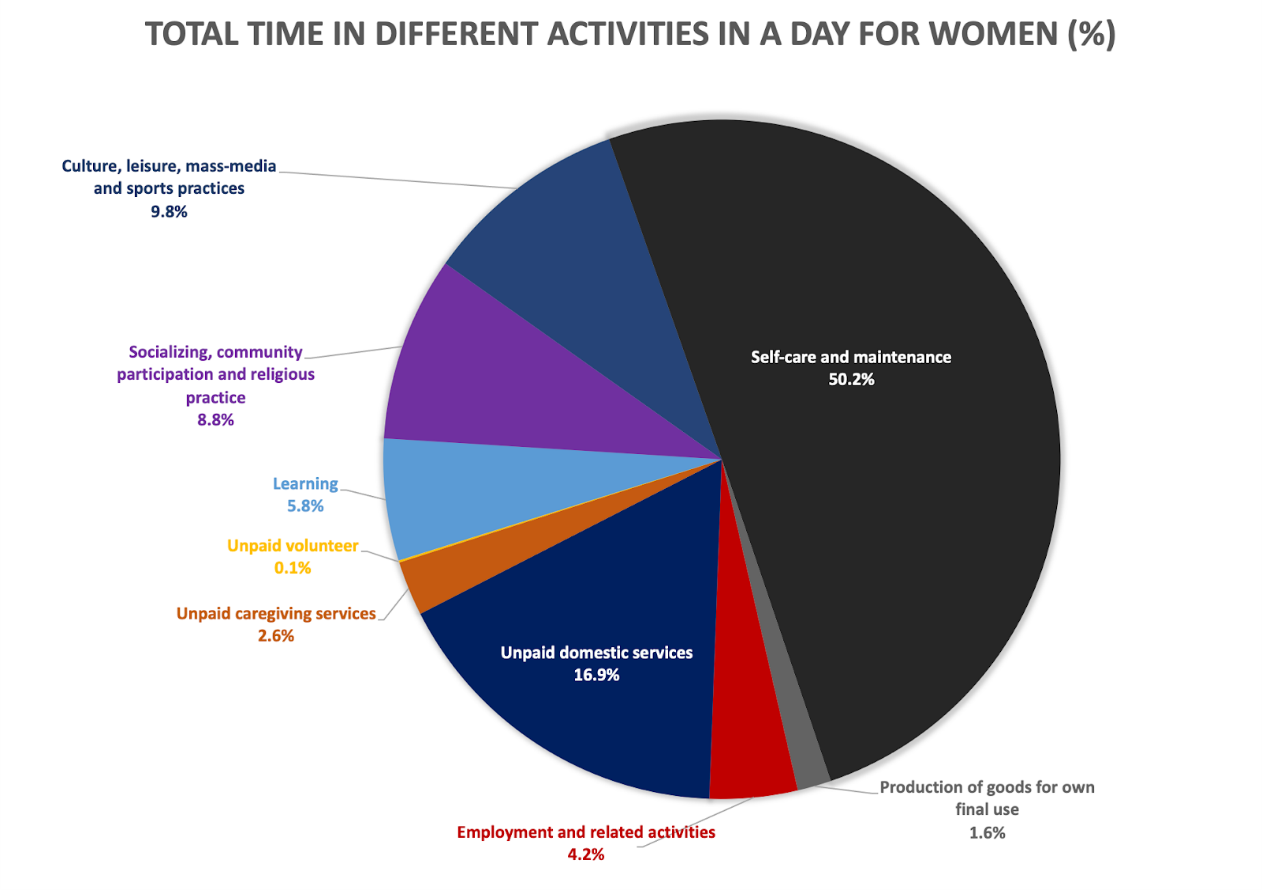

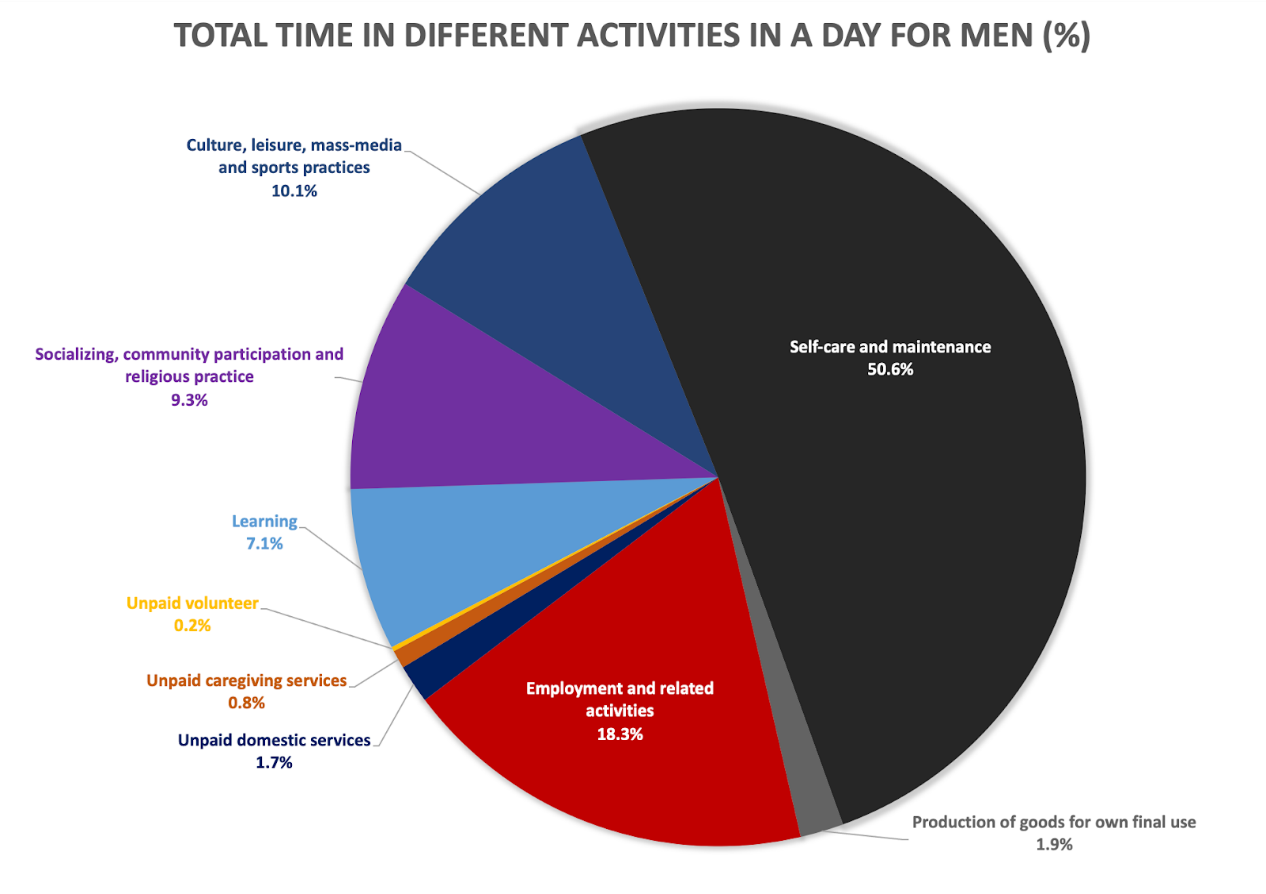

The time use survey shows that the average Indian woman spends 19.5 percent of her time every day in unpaid work including housework and caregiving as compared to just 2.5 percent of time spent by men. They also do over three times the amount of childcare as men. With schools, anganwadis, and other childcare centers closing down due to the pandemic, women’s time spent on childcare is bound to increase, affecting both their paid and unpaid work, unless men shoulder some of the responsibility.

Figure: Bansari Kamdar. Data: MOSPI

In India, the intersections of caste and geography also play an important role in determining gendered division of time and labor. The survey divided individuals into Scheduled Caste (SC), Scheduled Tribe (ST), Other Backward Castes (OBC), and Other Castes (OC). When OC was used as a proxy for individuals from upper castes, the survey finds that women from the upper caste engaged in the least amount of paid work while upper caste men did the least amount of unpaid work.

This is concurrent with recent research by Mukesh Eswaran, Bharat Ramaswami, and Wilima Wadhwa that finds that the ratio of women’s paid work to that of men declines as family wealth increases. This decline is steeper as we move up the caste hierarchy in rural India. Further, while upper caste women are more likely to be educated, the effect of higher education on women’s market work is weaker for the higher castes.

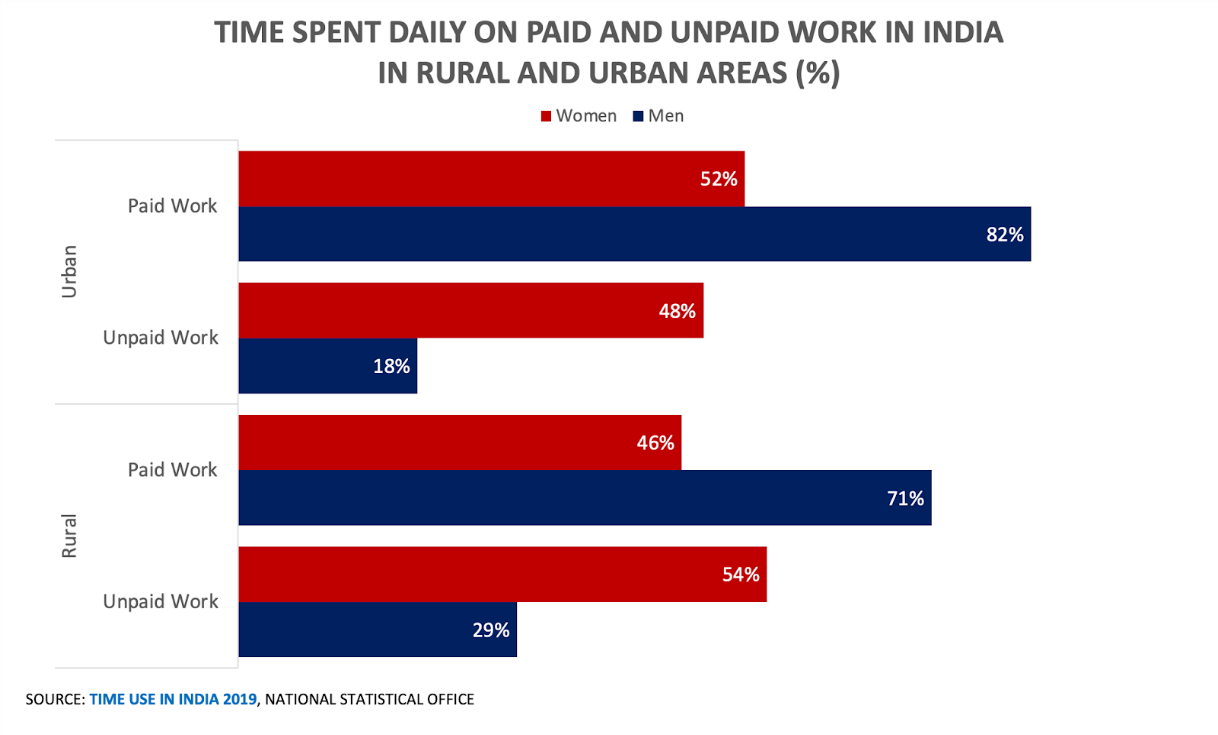

Similar differences also exist in women’s time allocation to paid and unpaid work by geography. In rural areas Indian women spend over six and half hours in unpaid activities and in urban areas they spend a little less, just a little more than six hours. Men in urban areas spend less time than men in rural areas on unpaid work, at just 31 minutes a day.

Figure: Bansari Kamdar. Data: MOSPI

Women are more likely to spend less time in unpaid work and men are less likely to contribute to housework in northern states over southern states. Haryana is the most unequal among the Indian states with men aged between 15-59 spending just 15 minutes on unpaid housework every day while women of the same age do 269 minutes of unpaid housework.

Social norms expect women to perform unpaid labor in India and the consequences for straying from the norm can be harsh. OXFAM India’s 2019 household care survey found that one in three survey respondents thought that it was acceptable to beat a woman for failing to care well for the children or not attending to a dependent or ill adult member in the household.

For failing to prepare a meal for the men in the family, 68 percent of survey respondents thought that women should be harshly criticized and 41.2 percent thought that they should be beaten. A 2016 survey by Economic and Political Weekly found that around 40-60 percent of women and men in rural and urban parts of India believe that married women whose husbands earn a good living should not work outside the home.

Research has shown that employment and earnings increase women’s bargaining power in the household and have positive impact for women and children’s wellbeing. McKinsey’s 2018 report also finds that advancing gender parity in India would have a larger economic impact than in any other region in the world— predicting $700 billion of added GDP in 2025. This can be achieved by increasing India’s female labor force participation by just 10 percentage points, increasing the number of paid hours worked by women, and adding more women to higher-productivity sectors.

This year’s time use survey is the first to be conducted across India after a pilot survey was conducted in 1998-99 in six states. There are two major concerns regarding the methodology of the time use survey raised by Jayati Ghosh and C. P. Chandrasekhar.

First, it relies on the recall method that asks respondents about their activities for the last 24 hours. This is considered inferior as people are often unable to recollect their time and may be involved in multiple activities at the same time. Second, the survey relies on responses by other household members for around half of the men and one-third of the women.

They conclude that even with the limitations of the methodology, the survey provides strong evidence of women’s “time poverty” that needs to be better addressed by policymakers.