Zahra Hamidi was preparing to go back to her senior year of school in late March 2020 after the three-month winter break. Then COVID-19 swept through Kabul, and schools went into lockdown. At the end of the lockdown in the summer, COVID-19 was still spreading and schools remained shut. And Hamidi, 20, was working as a tailor to help her family survive the pandemic, instead of distance learning.

Before the lockdown, Hamidi enjoyed family support for her education and was set to graduate from high school this year. But the lockdown left her father, a middle-aged manual laborer, in despair, as his daily income dried up. Hamidi and her young sister set up shop as dress tailors working out of their home, taking over financial responsibility of the eight-member household. Within months, Hamidi became a full-time tailor instead of a senior high school student.

When public schools reopened in the fall, Hamidi was two weeks late in signing up for her class. She said she was sent to another class in vain. As she remains the breadwinner of her family, she faces long odds of returning to school and graduating. “My mom says I should go school next year and graduate, but I am not sure what will happen then,” said Hamidi.

In Afghanistan, the COVID-19 response has hit education hard, which has had a disproportionate impact on vulnerable students like Hamidi. Nationwide school closures have added to the challenges already facing the country’s education sector, which has struggled to meet the public’s high enthusiasm for education in recent years. Even as schools reopen, the long-criticized curriculum and textbooks remain an area of contention for the country.

“Afghanistan was already facing a learning crisis,” said Freshta Karim, founder of Charmaghz, a mobile library for children in Kabul. “The most vulnerable children – girls and child laborers –were at higher risk of dropping out with schools closed for months.”

With the country’s academic year running between March and December, the national lockdown in March in response to the COVID-19 pandemic dragged the winter break out into the summer. The education ministry promoted distance learning using radio and TV stations, but as much as 70 percent of the population has no access to electricity.

To make things worse, the lockdown failed to prevent the spread of COVID-19. Afghanistan returned to business as usual in May and June, even while COVID-19 infections and deaths surged across the country. The official count of COVID-19 cases and deaths remained low, though, in part because of the low testing rate – the country had tested just 127,882 people as of November 12, and had reported 43,403 positive cases with 1,626 deaths as of November 16.

Even as the country reopened, schools remained closed for months. On August 22, the Education Ministry and Higher Education Ministry finally reopened universities and the senior and junior classes of public schools along with private schools. The Health Ministry said that reopening educational institutions did not lead to a rise in COVID-19 cases, but public elementary and primary schools remained shut for another month.

“If the entire country remained locked down, school closures would make sense,” said Karim, who advocated for reopening schools. “This policy of reopen everything and shut schools did not work. As children of the policymakers study abroad and/or attend private schools, it was hard for them to see the consequence of shutting schools.”

On September 29, the public elementary and primary schools reopened for school children after 10 consecutive months of break. A month and a half later, on November 15, the Education Ministry announced November 20 as the beginning of the winter break, meaning Afghanistan’s schools will have, in essence, skipped one academic year due to the pandemic. The long time out of school increased the chance of dropouts and children falling behind in their education, as young children disengaged from textbooks, said Karim.

The school closure coupled with economic hardship caused by the pandemic could have pushed a new record number of children out of school and forced them into child labor. In a country where 90 percent of the population lives on less $2 a day and desperate families rely on children for their survival, the pandemic has left invisible scars on children.

Last month, U.N. Women, UNICEF, and Human Rights Watch jointly issued an alert statement on the impact of COVID-19 on women and girls’ education. As girls tend to do house work, “the increased burden of care is hampering female students’ learning time, resulting in increased learning loss, and affecting their return to schools,” said the statement.

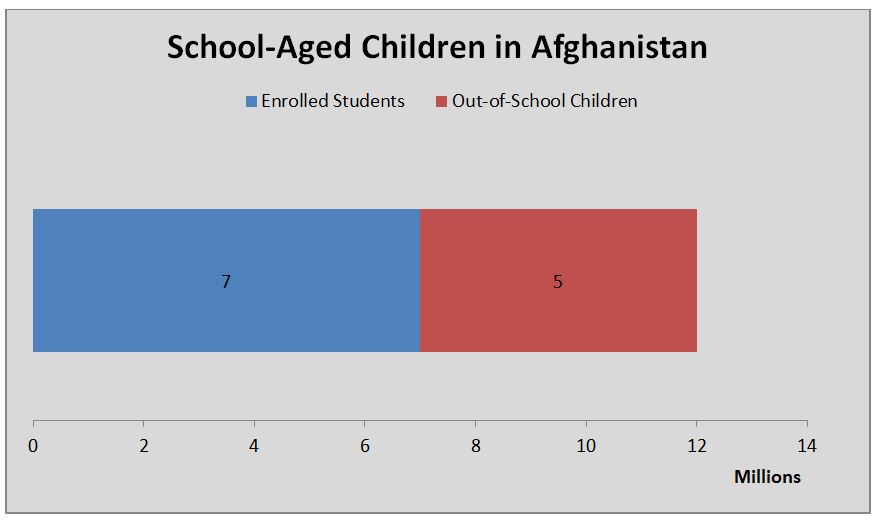

Out of 12 million school-aged children in Afghanistan, 5 million are currently out of school – possibly more.

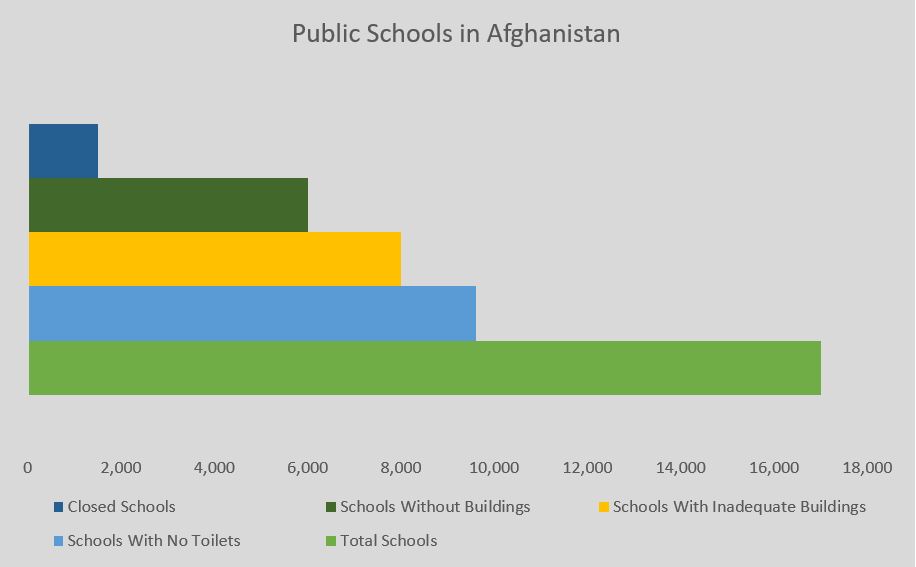

Even before COVID-19, the Education Ministry said 5 million children were already out of school. PenPath, a non-profit education organization in Afghanistan, disputes the estimate, putting their own estimate at 6 million children. As many as 1,500 schools remain closed, according to PenPath, but as the war drags on, more schools could be closed.

The Education Ministry acknowledges that 6,000 schools have no buildings at all and 50 percent of the country’s 17,000 schools lack adequate facilities. In Kabul, the capital, schools are overcrowded and students study under tents and ruined buildings. Throughout Afghanistan’s 34 provinces, 75 percent of students face textbook shortages.

“Parents want and love to send their children to school,” said Matiullah Wessa, founder of PenPath. “They have specific and basic demands, such as buildings for schools and female teachers for girls. For a girl school, having a toilet is a must,” although this is something that 60 percent of public schools lack.

Data from the Afghan Education Ministry, Human Rights Watch, PenPath, and the World Bank.

Wessa said that he had brought a petition letter to the Education Ministry requesting that the government open up a school in Jindah, Gilan district of Ghazni province, where 600 students did not have access to education. The Education Ministry refused to open a school there. “If we eliminate corruption and spend the current Education’s budget, no child will be out of school,” said Wessa.

Instead of building real schools and enrolling real students, the Education Ministry has been accused of paying ghost schools, ghost teachers, and ghost students. In 2015, the Special Inspector General for Afghanistan, a U.S. watchdog, questioned the entire U.S. aid money spent for education, a total of $769 million. The exact scale of corruption remains unknown.

The most shocking crisis is in teaching staff. As of March 2019, as few as four in 10 teachers had mastered the fourth-grade language curriculum and fewer than 40 percent of them had mastered the fourth-grade mathematics curriculum, according to the World Bank. In addition, even for Afghan children who do attend school, the average teaching time is just 3 hours and 25 minutes per day, among the lowest in the world.

“Even if we have schools, we do not have high quality teaching at our schools,” said Wessa, who is traveling across the country to reopen schools. “That’s why a student graduates from high school and joins terrorist groups, and becomes a drug abuser. We have failed to create a distinguished difference between a high school graduate and an illiterate person.”

One reason is the school textbooks. The school system is divided into three levels. Grades 1-4 use six textbooks that teach basic mathematics and one native language. Grades 5-6 use nine textbooks that teach basic science and two languages, and grades 7-12 use a whopping 17 textbooks that teach chemistry and physics, mathematics, and multiple social sciences.

The textbooks are not integrated, said Moqim Mehran, a high school teacher in Kabul. With many teachers struggling to master the fourth-grade curriculum, a majority of students are unable to read and write by the fourth grade and sixth grade, respectively. Many students struggle to read and write upon graduation. Given that context, the high school curriculum – calculus is mandatory for all students, for example – weighs heavily on students.

“For eight years, students study the English and Pashto languages (as a second language for non-Pashto speakers), but what they cannot speak is English and Pashto upon graduation,” said Mehran, who is director of the literature department at Marefat High School, a private school. “The Education Ministry sees designing textbooks as a project and does not have a good understanding of textbooks.”

The result is that students largely bear the burden of their own learning. Habiba Halimi, a senior high school student at Zainab Kubra High School in Kabul, learned reading and writing at home one winter break, studying with her father, rather than with teachers at school. Halimi quickly topped her classes and became a straight A-student at school from 7th grade until senior class.

“We always memorized textbooks,” said Halimi. “We studied the law of gravity at school, but we did not learn how gravity works. We did not ask questions. I took extra classes after school at a private educational center. Then I questioned everything. ”

At the heart of the crisis is Afghanistan’s curriculum: the general theme and aim of the textbooks. The curriculum is designed to prepare students, in the most hopeful scenario, for the Kankor exam, the country’s national university entrance test. But it largely fails at that task. Most interested students take extra classes at private educational centers and study all the subjects over again in order to pass the exam.

To give one example, in the current curriculum, Farsi and Pashto literature – key subjects for developing critical thinking – are treated merely as a means of communication, said Mehran, the high school teacher of Farsi literature.

“The literature subject just contains historical information on poets and novelists and does not discuss [the] meaning of their works. It is not treated as a means of thinking,” said Mehran. “This has undermined the education system. Literature is a means of thinking and should help students to develop their thinking skills.”

Mehran and others urge a change of the curriculum in a bid to help students succeed in their lives. These calls, however, are invisible in a country that faces multiple integrated crises, from widespread war to widespread poverty. Change in one sector in the country requires change in other sectors, but an effective education system could save the younger generation from the older generation’s bluster.

“If our education was dynamic, we would have a better generation after 20 years. Had we invested heavily on education, we would be in a better situation and would have done fundamental work,” said Mehren. “Inadequacy in the education system partly drives the country’s conflict.”

Despite its many defects, the education system has helped a scattering of students to thrive. Mehran studied at a public school and graduated from Kabul University. Karim, the director of Charmagzh mobile library, is likewise a product of the Afghan education system. “Hundreds of teachers toil for students, and there are many staff who candidly work. We have this system,” said Karim, who graduated from a public high school, studied at an Indian university and obtained a master’s degree from Oxford University.

Halimi, the high school senior, delights in school. With her parents both working full-time, Halimi turns to her teachers for life advice. She speaks English, volunteers at local clubs and NGOs, attends conferences, and went abroad for a winter camp last year.

“I enjoyed going to school and having friends, but I am unhappy with the courses of the school,” said Halimi. “As I am going to graduate within months, I am not the student whom I expected to be upon graduation with multiple skills.”