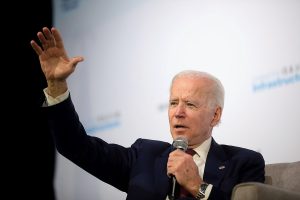

While the counting is still ongoing in several states, the results suggest former Vice President and Democratic Party candidate Joe Biden has defeated the Republican incumbent, Donald Trump, in the U.S. presidential elections. During the campaign Biden talked at length about issues directly important to Seoul, such as approaching the North Korea nuclear question and managing alliances, but his taking office in South Korea’s second largest trade partner will also likely be of major significance for the country’s economy.

A key pillar of the bilateral economic relationship in recent years has been the U.S.-Korea Free Trade Agreement (KORUS FTA). The deal was first signed in 2007, but only went into force in 2012, after a delay of several years to address U.S. beef and auto concerns. Since then, total annual bilateral trade in goods has steadily increased each year, reaching $134 billion in 2019, up nearly $34 billion from the 2011 pre-agreement baseline. Even before Donald Trump took office and actively pressured foreign companies to invest in the U.S., the agreement also helped to support foreign direct investment (FDI) between the two countries. Compared to 2011, South Korean FDI in the U.S. doubled to over $40 billion by 2015 and was up to $61 billion as of last year, directly supporting nearly 60,000 American jobs in 2017, according to the latest available figures from the U.S. Department of Commerce.

Despite these benefits to the American economy, Trump’s intense focus on the bilateral trade deficit led to a serious strain on the relationship, narrowly avoiding Washington’s withdrawal from the KORUS FTA. Though U.S. exports had risen during some years under the agreement, by the time Trump took office in early 2017 U.S. goods exports to South Korea had slipped below what they were before the agreement, while South Korean goods sent to the U.S. had increased by over $10 billion. Trump’s prescription was to renegotiate what he called “a horrible deal,” even though most experts agreed outside macroeconomic factors – including price fluctuations for U.S. agricultural products – were the underlying cause of the goods deficit, not to mention that Washington’s trade surplus in services with Seoul had grown under KORUS. The amendments both sides agreed to in September 2018 were welcome in that they allowed the White House to claim a win and move on, but they did little in the way of fundamentally shifting the bilateral trade deficit.

While revisiting the KORUS FTA again is just as unlikely to occur under a Biden presidency as it would have been during a second Trump term, Biden is far less likely to inject as much uncertainty into the economic relationship. Trump’s “us vs. them” outlook in his international agenda – made clear in the KORUS renegotiation – as well as his knack for unconventional maneuvers to achieve his goals, such as placing section 232 tariffs on South Korean steel imports on national security grounds, has made it difficult for companies to confidently navigate relationships with the United States. It can be argued that this uncertainty spurred short-term investment and purchases to allay the president’s concerns, but it has constrained long-term planning in what has otherwise been seen as a relatively stable market. Although Biden’s international economic platform has come under criticism for stressing the need to ramp up the domestic economy first, his greater emphasis on cooperation with allies and like-minded countries suggests he will push to stabilize bilateral economic ties.

Biden’s less confrontational approach could also benefit the South Korean economy on the global stage as well. With exports representing around 40 percent of GDP, South Korea’s economic success is intertwined with the rules and norms governing open international markets, which the U.S. played an important part in promoting after World War II, all the way through the Obama administration. Trump’s “zero-sum” agenda contradicted this, but Biden’s outlook – which is slated to better acknowledge the mutual gains from cooperation – could bring Washington back closer to its traditional role, albeit with limitations.

Biden was a major proponent of the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP) as vice president before Trump pulled the U.S. from the agreement on his first day in office. Biden has stated he would not seek to rejoin, but rather renegotiate U.S. re-entry into the mega-regional trade agreement as president, with a greater focus on labor and environmental issues. Although Seoul was not party to the original agreement or its “Comprehensive and Progressive” successor (CPTPP), it was seriously considering joining – likely even planning to eventually join – before the U.S. dropped out. The agreement is widely seen as key to building stronger trade rules more broadly, which the South Korean economy would assuredly benefit from. Though the CPTPP has been signed and entered into force, without the U.S. it is unclear if its leaders have enough heft to build on the momentum elsewhere.

Looking beyond the TPP, the shift in U.S. policy under Biden could help the South Korean economy in other ways. Without Trump’s singular focus on the bilateral trade deficits in goods, Biden can potentially look toward crucial global issues such as digital trade and green technologies to address climate change, both of which are increasingly vital to South Korea as the government looks to promote these already competitive areas to help recover from the economic fallout from COVID-19. Moreover, Biden’s stance on a more qualified competition with China could facilitate greater cooperation in international institutions dedicated to fighting the economic effects of the pandemic. Trump’s dogged pursuit of laying the blame for the virus on China has hindered a coordinated G-20 emergency response to the crisis as well as led to the United States’ planned withdrawal from the World Health Organization. A better coordinated global response to COVID-19 could mean a faster global recovery, which would mean a stronger bounceback for the South Korean economy.

However, South Korea should not expect a total and complete reversal in U.S. policy, nor for it to happen overnight. The U.S.-China competition – probably the issue of highest concern directly influenced by the election for South Korean companies – is not likely to go away. Biden may look to ease the pressure in certain regards, but may be less inclined to back away from decoupling high-tech value chains in the face of increasingly bipartisan support. Additionally, Biden’s emphasis on addressing economic issues at home first could mean it may take some time for the U.S. to pursue major international economic initiatives. This is compounded by the expiration of congressionally mandated Trade Promotion Authority at the end of June, giving him a very narrow window to get a trade agreement ratified before it would need to go through the process of being renewed. Of course, there are still some low hanging fruits that can be tackled more easily, such as no longer blocking the appointment of judges to the World Trade Organization’s Appellate Body.

Overall, Biden will help to ease some of the tension and uncertainty that Trump has infused bilaterally and at the global level over the past four years, but he will nevertheless be constrained by the realities of a struggling economy at home, shifting geopolitical power, and shaken faith in U.S. leadership. Still, the Biden administration should provide a welcomed window of opportunity to advance key economic priorities shared by both countries and the global community.