China afficionados will easily recognize images of delicately traced mountains and sprawling lakes. Epitomizing an ideal manifestation of nature and traditional values, these images were once upon a time featured on the calendars of every Chinese home. But now imagine these landscapes in popping colours, superimposed by rainbow-colored WordArt, neon-blinking emoticons and smiling models. This is just one form of 土味, a term that when unpacked sheds light on a changing China.

土味 (tuwei) literally means something that has the flavor of soil. Figuratively it refers to something that is either tacky cool, outdated, or cringe-worthy and sometimes of bad taste.

Tuwei culture made its debut on Chinese social media in the mid-2010s as a form of mockery or irony, poking fun at popular folk culture. It involved a new generation of Chinese creators and commentators who chose to take the nostalgic Chinese visual cues they grew up with and use them in their own modern context.

As a patchwork of experiences, tuwei culture’s initial influences included many of the trends that dominated China since opening up – kitsch wallpapers and paintings in restaurants or karaoke bars, idealistic nature imagery, counterfeit fashion in third-tier cities, Japanese childhood cartoons, and the “memes” of classical nature superimposed by motivational phrases that became so popular amongst older generations at the cusp of this century.

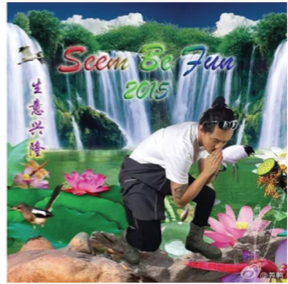

An early example of a tuwei meme.

Today, this culture continues to evolve as new generations are adding their own experiences to it. It can be observed on Weibo or WeChat, but is also referenced by artists, on TikTok, and even in fashion (where tuwei has taken on a meaning similar to what we might call “vintage” in the West).

With Gen Z the concept has lost its tinge of self-mockery and has become part of their growing sense of national pride and nostalgia. As a contender to the “chic minimalist” style of the refined urbanite, tuwei has provided an alternative sense of identity for the young, fashion-conscious urban Chinese. As “Made In China” is often equated with poor quality, a key point of tuwei culture is to embrace this style and question whether those bright colors, misspelled words, and loud graphics are indeed “tu” – i.e. of poor taste.

Tuwei style has also been copied in third-tier towns and rural areas, where urbanites often mock it as a cheap imitation of first-tier cities. Yet on Tik Tok and Kuai Show (a video sharing and live streaming platform popular in rural areas), rural influencers making tuwei-style videos have amassed millions of followers and views. Many of these videos are highly entertaining, attracting city dwellers who admire the brazen behavior of these actors – a form of escapism in a world-class city, where you are expected to behave.

By failing to understand these kinds of subtleties in modern culture, luxury brands trying to localize have not had an easy relationship with Chinese consumers. Controversial encounters have ranged from outright racism and misunderstandings, to subtler insensitivities – such as Balenciaga’s Valentine’s Day ads in early 2020. Featuring tuwei nature illustrations and kitsch emojis, they were meant to strike a chord with the young and cool Gen Z . But instead of this, they became seen by many as offensive, tacky, and an insult to modern Chinese taste.

Balenciaga’s Valentine’s Day ads in 2020 triggered a backlash.

What Balenciaga failed to fully understand is that fashion-conscious urban youth adopt tuwei as a rebellion against the aspirational lifestyle they are expected to pursue in a big city. But this attitude of rebellion and “mismatched but cool” style only works when it comes from the bottom-up, not when it is imposed by luxury brands. In the hands of foreign brands, it became bad taste, rather than attractive or escapist.

As we are looking toward the upcoming Chinese New Year and Valentine’s Day, it will once again be time for major ad spends and campaigns. With multiple mentions and comments on social media, perhaps Balenciaga achieved exactly what they intended by going so local – to become part of contemporary debates. But as local Chinese brands continue to grow in number and influence, it might be worthwhile for brands to ask themselves whether they should not retain their “foreignness” after all. Because let’s face it – who can do Chinese more authentically than the Chinese themselves?

Laura Grunberg manages regional digitalization projects across East and Southeast Asia. With a passion for consumer and digital trends, she was a Yenching Scholar at Peking University where her research focused on the consumption upgrade and retail in China. She holds a BA from the University of Cambridge in Human, Social and Political Science.

Yi Jing Fly is the author of “China Too Cool: Vernacular Innovations and Aesthetic Discontinuity of China.” With a background in fashion design as well as critical and visual studies, her interest lies in understanding society through aesthetic and consumer trends.