Alice Miller was a pioneer in using institutional analysis of elite Chinese politics to predict institutional and personnel changes based on a combination of Chinese Communist Party (CCP) organs, party cadres, and historical party institutional analysis. Now in most cycles of CCP administration, analysts compete to offer insight into possible forms of institutional change. Ahead of the 2022 Party Congress, institutionalists have already begun personnel analysis as well as wider macro policy directional analysis. This work assumes that the past institutional forms are an indicator of future structures. But in the lead up to the 19th Party Congress in 2017, Jessica Batke was correct to note that much is written about Chinese politics assuming to know more than we really do.

If the state ideology does not change, then any changes to the institutional superstructure can only be superficial. While there have been important recent changes in political rhetoric and ideology, as well as macroeconomic policy and national system direction, they are not enough to expect wholesale institutional changes in the party cadre system or other internal party institutional changes.

Policy-wise, dual circulation, demand-side reform, and an imminent political and legal rectification campaign are the important agenda items for 2021. Between this rectification stick and the demand-side reform carrot, there is a lot of political space to clean out opposition, block promotions of the unanointed, reward the policy competent who emerge from the subnational competitions, and strengthen incumbent political factions going in to the 2022 Congress. As 2021 policy progresses, we should begin to see this 2022 political space open up.

Managing personnel changes in the 2022 Party Congress is now a huge task for the CCP because this should be an institutional transition of renewal. However if top leader Xi Jinping does successfully maneuver to stay on, it would mean breaking many institutional conventions and having to manage close party appointments very carefully. It is very difficult to allow even a modicum of political renewal within a Communist Party and there will be many party cadres who stayed quiet through the ten-year Xi administration because they expected to come out in to the sun in the 2022-2032 period of elite leadership. Managing them is the personnel problem facing Xi now.

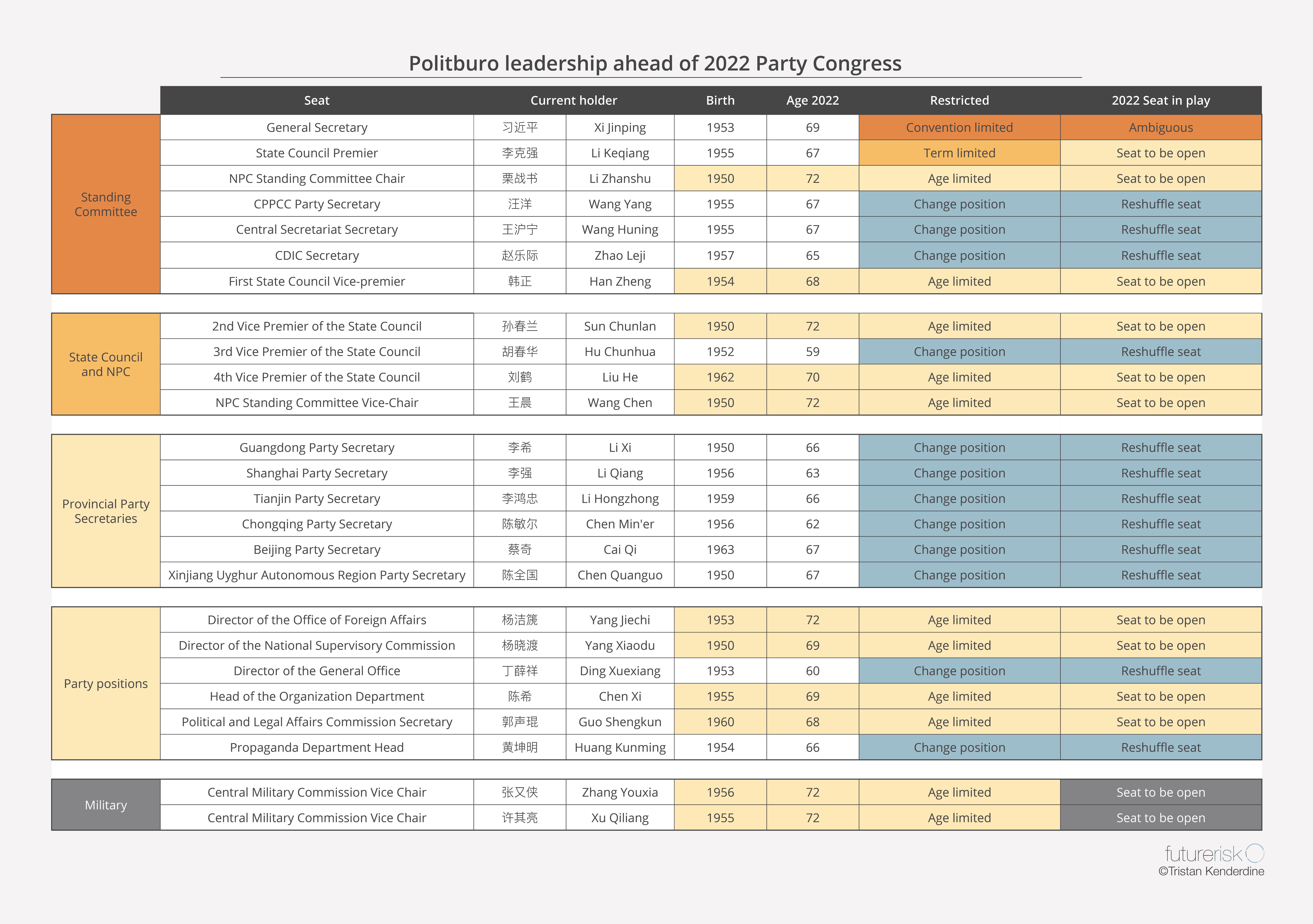

The main institutional rule remains the “seven up, eight down” system, where party cadres are promoted or retired based on age: those aged 67 and younger can be promoted, with promotions within the hierarchy halted after 68. There are also still two-term limits on the State Council positions of premier, the four vice premiers, and five state councilors, so in 2022 Premier Li Keqiang can stay within the Politburo Standing Committee, but must change seats. The CCP’s general secretary was limited by convention to two terms, so although Xi removed the legal two-term limit for the largely ceremonial state position of President, the party position of general secretary should still be limited. But most observers both within and outside China expect Xi to at least try to maintain power for a third term.

In the current Politburo there are nine non-military and two military seats that must be vacated in 2022 by the age restriction rule. Of the remaining 25 seats, 12 are candidates to be reshuffled, with the possible exception of Wang Huning, and by term limit rules there should be a new State Council premier chosen from either the reshuffled candidates or a new entry. Most of the party governance positions retire due to age restrictions too. Guo Shengkun should make way for Zhao Keji as the top domestic security official and Yang Jiechi will leave, opening a space in the foreign affairs portfolio.

Within the current Politburo, most of the State Council and National People’s Congress chairs retire from age, with the exception of Hu Chunhua. Most internal reshuffles from within Politburo will be towards these seats. All of the provincial boss chairs are young enough for at least one more term, with Chen Min’er eligible for two more terms. Two or even three of these current provincial bosses are can move up into the Politburo Standing Committee and the remainder can move into the other state or National People’s Congress positions, which then creates room for external candidates for the big provincial seats.

Within the current Politburo, most of the State Council and National People’s Congress chairs retire from age, with the exception of Hu Chunhua. Most internal reshuffles from within Politburo will be towards these seats. All of the provincial boss chairs are young enough for at least one more term, with Chen Min’er eligible for two more terms. Two or even three of these current provincial bosses are can move up into the Politburo Standing Committee and the remainder can move into the other state or National People’s Congress positions, which then creates room for external candidates for the big provincial seats.

These provincial party secretary places are the staging grounds for future Standing Committee candidates, meaning whoever is promoted from these positions will be very important in the 2022-2027 administration, and whoever is promoted to these positions will be important in the 2027-2032 administration. The standouts at the moment are Li Xi, Chen Min’er, and Chen Quanguo, all of whom could ascend into the Standing Committee given the right scenarios playing out in their favor. And whoever is promoted to replace any of the party secretary positions of Guangdong, Shanghai, Tianjin, Chongqing, Xinjiang, or Beijing is indicative of the form of higher leadership being prepared for the 2027 administration.

For the nine wholly vacated seats in 2022, there are only so many institutional places from which candidates can be drawn. The main institutions that yield potential Politburo candidates are central party organs, provincial party secretaries, provincial governors, State Council ministers, and the party secretaries and mayors of the 15 subprovincial level cities. This is the basic pool of candidates and assessing this level of the public administration hierarchy yields the contenders for both this upcoming and future Politburo ranks. There are SOE leaders with the requisite party cadre rank of zhengbu, and there are political outliers like the Wang Qishan or Liu He paths to peak power, but essentially there is a pool of around 120 party cadres with the zhengbu rank who currently serve in city, provincial, ministerial, or party institutions.

The 20th Party Congress Politburo will be an attempt at institutional rigidity in an administrative term conventionally marked for change. This means extending loyal personnel in the cadre system into their final career term for the Xi project’s 2022-2027 administration, rather than empowering candidates with two terms left in their careers who could serve for the entire 2022-2032 period. This introduces a new form of institutional friction into China’s political system.

There remain serious limitations to using institutional analysis to determine future path dependencies in China’s Politburo. No one can predict factional changes in power, political purge campaigns, or the violation of institutional conventions. But the party cadre system remains the most resilient political institution in modern China, the machinations of which will continue to determine many political and policy outcomes in the 2022-2032 period.