Yesterday brought two announcements that would likely have been unwelcome news to the new military junta that now rules Myanmar. The first was that Japan’s government is considering suspending new official development aid for the foreseeable future, in response to the February 1 coup.

Chief Cabinet Secretary Katsunobu Kato told a news conference that negotiating and agreeing to new assistance would be too thorny for the Japanese government under the current circumstances. “Regarding economic assistance for Myanmar, we will carefully monitor the situation without prejudice,” he said.

The second piece of news was the Japanese automotive giant Toyota’s decision to postpone the opening of a new plant in Myanmar, given the heightened political uncertainty that has followed the military takeover.

The 5.5 billion yen ($52 million) plant was scheduled to open this month, but as tensions between the military and anti-coup demonstrators increase, Toyota concluded it would be difficult to proceed. “The timing for the opening remains under discussion,” a source at Toyota told Nikkei Asia.

Toyota’s decision comes after the Japanese beverage producer Kirin withdrew from its joint venture partnership with the military-linked conglomerate Myanmar Economic Holdings Limited, and other firms have come under pressure from anti-coup protesters and rights groups to cut their ties to the military junta.

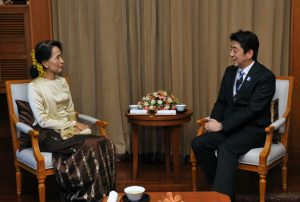

The coup, which saw the military detain State Counselor Aung San Suu Kyi and abrogate her party’s massive victory at elections in November, has shaken Japan’s approach to Myanmar.

For years, the Japanese government has engaged pragmatically with Naypyidaw, maintaining ties with the armed forces and working to promote investment in the country. Economic and diplomatic ties have both expanded rapidly since the country’s political reforms began in earnest in 2011.

In 2019, the Japanese government provided 189.3 billion yen ($1.8 billion) in official development aid (ODA) to Myanmar, making it the largest donor to the country aside from China, which does not publish its numbers. In addition, some 450 Japanese companies operate in Myanmar, mainly in the manufacturing sector, up from 53 in 2011. Japan is the fifth-largest foreign investor in Myanmar, following Singapore, China, Hong Kong and Vietnam, according to government figures.

This has been paralleled by a strategy of pragmatic engagement, which has seen Japan maintain cordial relations to the Myanmar military and government, despite human rights abuses. Tokyo’s calculation has been rational, fearing that any withdrawal will open up a vacuum for its rival China. In the interests of maintaining level relations with Naypyidaw, Japanese diplomats have gone so far as to avoid using the word “Rohingya,” and to back Myanmar’s claim that the assaults on the Rohingya did not amount to genocide, a move that has earned it frequent rebukes from human rights groups.

“As a major and influential donor, the Japanese government has a responsibility to take action to promote human rights in Myanmar,” Teppei Kasai of Human Rights Watch said in a statement this week. “It should urgently review and suspend any public aid that could benefit the Myanmar military.”

Despite such urgings, Japan has been reluctant to follow the United States and European nations in imposing sanctions on the Myanmar military and its economic enterprises since the coup. “If we do not approach this well, Myanmar could grow further away from politically free democratic nations and join the league of China,” State Minister of Defense Yasuhide Nakayama told Reuters shortly after the military’s seizure of power.

While Tokyo’s instinct is to hold the line and maintain lines of communication with the generals, its now coming under increasing pressure from public opinion inside Myanmar, which is hostile to any nation or company conferring legitimacy on the new junta, and from its Western democratic partners and allies, which are ramping up sanctions and pressure on the coup regime.

As Andrew Selth of Griffith University wrote recently, the Myanmar military’s February surprise has laid bare the failures of the various strategies that foreign governments have adopted for engaging Myanmar’s military: both the idealists who have sought to pressure it into change and the pragmatists who sought to coax it in that direction.

Given Japan’s long support for the Myanmar government, particularly during its era of semi-democratic reform, the loss of Japanese support and investment, even if limited, is likely to weigh more heavily on the junta than that of Western governments. Whether this is enough to affect the behavior of the generals, however, remains to be seen.