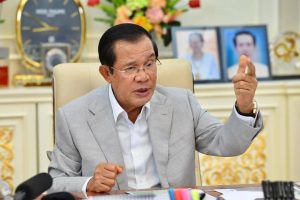

On Wednesday night, Cambodia’s Prime Minister Hun Sen gave a recorded address on state-run television in order to address the country’s alarming spike in COVID-19 infections.

“Please my people – join your efforts to end this dangerous event,” the long-time leader begged his country. “We are on the brink of death already. If we don’t join hands together, we will head to real death.”

Hun Sen also announced a two-week lockdown of Phnom Penh and the nearby town of Takhmau beginning on Thursday, which prevents people from leaving home except for going to work, to buy food, or for medical treatment.

Audio of Hun Sen’s message was leaked hours before the formal announcement. It spread rapidly on social media and prompted a rash of panic buying that left shops denuded of goods, scenes that have been witnessed in dozens of countries since the beginning of the pandemic.

“I appeal to all compatriots: please do not get into a panic like what we witnessed on the evening [of April 14],” he said, vowing to punish those officials responsible for leaking the recording.

As my colleague Luke Hunt noted in these pages earlier this week, the current spike is Cambodia’s third local outbreak of COVID-19, and is believed to have originated with two young Chinese women who bribed a guard and breached quarantine on February 20, allegedly to go out on the town.

On April 15, Cambodia recorded 344 new cases of coronavirus, followed by 262 cases today, bringing its total case load to 5,480 infections and 36 deaths. While this may seem modest compared to what is happening in, say, India, the outbreak follows a year in which Cambodia, through a combination of timely government action, accommodating cultural mores, and sheer luck, had managed to keep the virus mostly at bay. In the year to February 20, Cambodia recorded just 484 cases and no deaths from COVID-19.

Since the February 20 Community Event, as it is known, confirmed cases have mushroomed across the country, many of them the more infectious British variant of COVID-19, and the government has moved sluggishly to control the outbreak.

Hun Sen acknowledged in a speech on April 10 that “bad governance” had been a factor in the worsening outbreak, a surprising admission from a leader who is usually intolerant of criticism. Cambodian state-aligned media outlet fresh news reported on Thursday that a senior official from the Ministry of Information had died from COVID-19, a few days after the World Health Organization warned that Cambodia is on the verge of a “national tragedy.”

To combat the country’s third wave, a defunct hotel in Phnom Penh has been converted into a 500-room hospital, and authorities are enforcing a new law that imposes harsh penalties on those violating health and lockdown rules. Cambodia has shut down its most popular tourist destination, the temples of Angkor, for two weeks, while the nearby town of Siem Reap has also announced a two-week lockdown beginning today.

Banks and microfinance institutions have also waived interest payments in order to reduce the pressure of cash-strapped borrowers, while some Buddhist monks have expressed concerns that public support for the country’s monasteries and pagodas, especially those outside the capital, will decline.

As the pandemic first began to ravage the United States and western Europe, many observers pondered why the mainland Southeast Asian nations – Vietnam, Cambodia, Laos, Thailand, and Myanmar – had been so successful in keeping the disease at bay.

Cambodia’s third wave is a reminder that while COVID-19 can be controlled with great effort, any slackening of effort carries serious costs. A similar lesson is being learned in neighboring Thailand, which is currently undergoing its own third outbreak of COVID-19, and today announced new restrictions that could jeopardize its plans to restart tourism.

In Myanmar, meanwhile, the virus exploded in September, and was only under control by the time of the military seized power on February 1. Since then, testing and vaccination efforts have virtually come to a halt as the country has plunged into political crisis, making it hard to know how serious the country’s coronavirus situation is.

These various outbreaks in nations that once seemed strangely immune to the virus suggest that even with public vaccination campaigns well under way, the struggle against COVID-19 in Southeast Asia is likely to be a long one.